Paul W. Johnson is a preacher’s kid, former Iowa state legislator, former chief of the USDA Soil Conservation Service/Natural Resources Conservation Service, former director of the Iowa Department of Natural Resources, and a retired farmer. -promoted by Laura Belin

In the early 1980s there was a serious farm crisis in Iowa. Land and commodity prices were falling, so banks were calling in farm loans and foreclosing on farmers who couldn’t pay up. Maurice Dingman was bishop of the Des Moines area during those years, and he was speaking up strongly for farmers who were suffering during this time. I was impressed by his defense of family farmers.

In 1987 David Osterberg and I were serving in the Iowa legislature–he representing Mount Vernon, I representing Decorah–and working on groundwater protection. Industrial agriculture sent their lobbyists to weaken our legislation, and newspapers were carrying stories about their fierce opposition to our work.

During this time, Bishop Dingman phoned us and suggested we have lunch together.

When he called, we wondered what in the world a Catholic bishop wanted with a Methodist and a Congregationalist. We met and had lunch with him. He wanted to tell us not to get discouraged and to stand up for what we believed in.

He told us about being a theology student in the Vatican in 1939 and feeling that his church was not speaking up forcefully enough against Franco in Spain, Mussolini in Italy, and Hitler in Germany, because those dictators led countries with many Catholics. He said that since those days, he has been haunted with sins of omission, that he knew that his church should have spoken up. But it remained quiet. He felt it should have raised its voice strongly against injustice no matter who perpetrates it. He said that if your leaders or your church go against what you believe, you must speak out. Sins of omission are every bit as wrong as sins of commission.

One of my greatest concerns right now is that so many political leaders are committing sins of omission by going along with our president and refusing to deal with global climate change. This reminds me of our meeting with Bishop Dingman.

Even Abraham Lincoln, a person Republicans claim as the founder of their party, once said that what is morally wrong cannot be politically correct. And yet many leaders – governors, legislators, members of Congress, evangelicals, and too many in our farm community – continue to ignore the science of global climate change.

We are rapidly destroying the life support system of not only human beings but a million other species with which we share this planet. This is exactly what Bishop Dingman spoke to us about at that lunch 33 years ago: speak out about what you believe is wrong and what is right.

When I worked for the U.S. Forest Service 55 years ago, I was impressed with their commitment to the concept of multiple use. Along with managing for timber, they also managed our national forests for recreation, wildlife, water, and biodiversity. Although the multiple use concept doesn’t fit agriculture, multiple functions would. The U.S. Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) does this by using what they call the SWAPA concept (soil, water, air, plants, animals).

Iowa is a private lands agriculture state. Here are just some of the things that we could and should do, which would combat climate change and be an example for the whole world wherever agriculture is practiced. The beauty of these practices is that they would not only reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but also address many concerns about modern agriculture (SWAPA).

Conservation Reserve Program

The Conservation Reserve Program is the largest federal program promoting conservation on private lands. It began in 1985 primarily to take highly erodible land out of production to reduce soil erosion on our nation’s most fragile cropland. Over the years CRP has broadened its coverage beyond soil to include water, air, native plants, and wildlife (SWAPA).

Nationwide we now have about 24 million acres in CRP. Iowa ranks fourth nationally, with about 1.7 million acres. Contracts are typically for ten years but some, particularly if you plant trees, are for fifteen years.

Unfortunately very little credit is given for practices that address climate change. Nonetheless CRP is a major plus for sinking carbon. Studies have shown that land at the beginning of CRP contracts often has only 1 percent organic matter, but after ten years it often increases to 4 percent.

The next several practices that can address climate change as well as SWAPA are a subset of CRP but focus on targeted areas of the farm. Unless they are vigorously implemented when the contract expires, that 4 percent organic matter in the soil could soon be back to 1 percent.

Riparian buffers

Iowa has more than 50,000 miles of rivers and streams. As many as possible should be wrapped in native grasses and flowering or woody plants. These plants often send roots down six feet or more, and the vegetation above ground helps to stop bank erosion.

Our president continually touts the wall he wants to build. Iowa farmers have an opportunity to build a wall underground with the root systems of our native plants filtering water seeping through the soil profile, and a wall of thatch above ground to stop surface erosion into our rivers and streams. All of this vegetation builds organic matter in the soil profile, thus sequestering carbon instead of releasing it in the form of greenhouse gasses.

SWAPA? Yup. Farmers can get paid for establishing these buffers.

Contour strips

In the past few years farmers have pulled most of the fences within our square mile grid system. Only the roads now serve as fences, and our fields are now often 640 acres instead of four 160-acre farms, which were divided into many smaller fields.

These larger fields give us a better opportunity to contour farm. We should intersperse these crop contours with long, narrow strips of native species which provide biological fences that slow soil erosion and sink carbon. We have a federal program that pays a farmer for ten years to do just that.

These “fences” bring to mind how most farmers my age have rips in their work shirts from climbing through barbed wire fences. With biological fences we could just walk through them. Of course, we might be startled now and then by flushing up a pheasant or a meadowlark. Or we might be distracted and spend some time watching a killdeer feigning a broken wing to draw us away from its nest. Yes, some wire fences will be needed where there are animals, but today there are many alternatives to permanent barbed wire.

Bill Northey, the former director of our Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship now oversees the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and the Farm Service Agency, the two agencies that manage this buffer program. We need to urge our representatives in Congress to make sure that this program is fully funded, and that U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue and Northey aggressively implement it.

I first met Bill when I was chief of NRCS and was impressed by his commitment to promote conservation ideas in agriculture. I trust his heart is still in this.

Unfortunately, some farmers have discovered a new way to contour farm. We’re finding contours between electric poles into our public roadsides. No money for this one!

Another concern that I have deals with end rows. Our planting equipment is so large now that we often need at least 24 rows to turn around at the end of each strip. These end rows are then planted straight up and down the hills. At the very least these ends rows should not be tilled. Better yet, they should be converted to buffer strips using native species. The federal Farm Buffer Program will pay for these field borders as well as the contour strips. SWAPA? You betcha.

Nitrogen

Many activities in agriculture contribute to climate change, but the 800-pound gorilla that overpowers all of them is nitrogen. In addition, nitrates (NO3), the form of nitrogen used by plants, are a major water pollutant from agriculture.

Natural gas used to produce nitrogen fertilizer for agriculture is a major contributor of greenhouse gases. Close to 50 percent of the natural gas used in Iowa goes to make this fertilizer, and during the drilling, extraction, and transportation of natural gas, methane is released. As a greenhouse gas, methane is 30 times more powerful than carbon dioxide. Our president has recently weakened rules that would have greatly reduced methane losses at wellheads.

Another important greenhouse gas is nitrous oxide (laughing gas), which is 300 times more powerful than carbon dioxide! Agriculture is by far the largest contributor of this gas. It is directly associated with animal manures (thus, jokes about cows requiring diapers), tillage, and nitrogen fertilizer.

Nitrous oxide is no laughing matter, but as with most agriculture problems, research at places like Iowa State University could help us deal with this challenge.

Farmers are now experimenting with cover crops seeded in the fall. If growing conditions (moisture and temperature) cooperate, cover crops can capture and keep nitrates from leaching. These crops are then killed in the spring, and as they decompose, the nitrates are slowly released to be utilized by the new growing crops. Cover crops also will reduce surface erosion. It’s good to see how quickly this practice is catching on and how farmers are finding new ways to apply it.

Many agronomists say today that farmers are still using more nitrogen fertilizer on their corn ground than necessary. In addition to the greenhouse gasses emitted, much of this excess nitrogen pollutes our groundwater and surface water (drinking waters). It also flows through the ag drainage system to the Missouri and Mississippi rivers and on into the Gulf of Mexico, causing a huge dead zone. SWAPA? A no brainer.

Ag drainage

We ought to view drainage districts as “water management districts,” and we should re-engineer what we now call drainage ditches, requiring conservation practices such as restoring wetlands and floodplains where appropriate.

Let’s stop calling them ditches. These channels should be where we process water before passing it downstream, not just water disposal ditches. Farmers whose underground drain tiles discharge into the drainage channels should be required to follow conservation practices in order to reduce contaminants.

While we’re at it, let’s experiment with linear wetlands alongside some of our present drainage channels. We could divert waters through parallel reconstructed wetlands full of native species, thus sequestering carbon. We could measure nitrates (water pollution) in the drainage water that is diverted into these linear wetlands and then measure them again at the end of the wetland where the water flows back into the drainage channel.

Farmers could be paid for sinking nitrates through this process. We should do the same when farmers restore natural wetlands on their properties. There is good research going on at ISU on these issues right now, and early results look promising. SWAPA? Yes.

No-till

Another way to deal with global climate change through agriculture is to move as quickly as possible to no-till on our corn and soybean land. Right now, corn and soybeans make up more than two-thirds of our 36 million Iowa acres. Much of this land doesn’t need to be tilled every year. By reducing tillage, we can lessen greenhouse gasses coming from our soils by binding carbon in organic matter plus bring soil erosion closer to zero.

When prairies were first plowed in Iowa there often was more than 6 percent organic matter in the soil. In much of Iowa soil today we have just a fraction of that. By moving to no-till we can start building it back.

It takes a great deal of fossil fuel to till our land. Reducing tillage and thus decreasing use of fossil fuels will go a long way towards lessening agriculture’s negative impact on climate change.

Like many others, I have been concerned about no-till because of its dependence on heavy use of herbicides. However, many farmers who have used no-till say that they have actually been able to reduce their use after the first couple of years. We have a whole industry that wants farmers to use more herbicides, but I and many other farmers would rather see us use less. There’s room for additional research here.

There is some debate today about how much carbon can be stored deep in the soil profile. The science of carbon sequestration is not fully understood yet, but we do know that no-till farming will at least build beneficial organic matter in the upper soil profile. And as this organic matter breaks down, nitrogen is released slowly during the growing season, avoiding water degradation. The increased organic matter will also hold more moisture in the soil profile, thus reducing the negative impact of drought conditions.

At the very least we should not do fall tillage or apply nitrogen in the fall. Fall tillage increases soil erosion over winter, and applying nitrogen in the fall can lead to increased water pollution. SWAPA? Of course.

Animal confinement systems

We must pay much more attention to animal confinement systems. The best estimates are that there is sufficient nitrogen in the liquid animal waste from our confinement systems to supply at least a third of the nitrogen needed to grow corn in Iowa. Yet most of this animal waste is applied in spring and fall, when there are no crops growing to take up the nitrogen.

When we get heavy rains at either of those times, much of the nitrogen leaches through the soil into drain tiles. (We now have a million miles of these tiles laid under Iowa crop land.) The water containing nitrogen coming from these drain tiles and drainage channels dumps into streams, rivers, and on to the Gulf of Mexico, causing a huge dead zone in the Gulf called hypoxia. Recent research indicates that nitrogen from Iowa farms accounts for 40 percent of this dead zone. A better practice is to wait until the corn crop is growing to apply the Spring liquid animal waste.

Liquid animal manure from confinement systems that is applied in spring and fall typically contains very little organic matter. If we could increase the organic matter in this liquid manure (for example by shredding corn stover into it) and inject it into our soils, it would hold the nitrates and store the carbon, releasing them slowly so that they could better be utilized by the next year’s crops.

This is especially important after harvesting soybeans, since they leave very little ground cover over winter, and the more organic matter in the upper soil profile, the more nitrates will be stored. This approach would reduce nitrates in our drainage water and not allow as much carbon to volatilize into the air. It would take some research to be able to inject liquid manure with additional organic matter in it. SWAPA? Indeed.

Biodiversity

We need to recognize that our corn and soybean rotations have turned a very diverse ecosystem into a biological dessert, with only two species occupying more than two-thirds of Iowa’s land. We who live up here in the corn belt scold farmers in Brazil for destroying their rain forest but don’t even raise a finger about our destruction of biological diversity on Iowa’s prairies.

Buffers along rivers and streams, contoured grass strips, more diversity in our waterways, no-till, and field borders seeded into native species would go a long way towards building biodiversity back into our agriculture landscapes. They would increase wildlife, improve water quality, improve soil conservation, sink carbon, and yes, they would even improve the beauty of Iowa’s landscapes.

Iowa farmers could proudly show the world that they can contribute to reducing climate change while serving multiple functions rather than just growing corn and soybeans. I believe that no agriculture is sustainable if it ignores the health of the natural ecosystem where it operates.

Iowa native Aldo Leopold wrote in 1939, “the farmer who now seeks to preserve the soil must take account of the superstructure: a good farm must be one where the wild fauna and flora has lost acreage without losing its existence.” SWAPA? For sure.

Roadside vegetation

I’ve been amazed to learn that 60 percent of our public land in Iowa is in our roadsides. Just think of it. Every time you drive in the countryside, you’re driving next to some of your land.

We have an Integrated Roadside Vegetation Management Program (IRVMP) in Iowa, charged with bringing native species back into our roadsides. It is situated in the Tallgrass Prairie Center at the University of Northern Iowa. We ought to greatly expand that program. The Tallgrass Prairie Center should continue to be the coordinator of the program, but we could include community colleges, Regents Universities, private colleges, high school science programs, county conservation, Extension Services, garden clubs, and farmers (neighbors to all this public land) to help spread the program.

We should put together ecological teams in each county in the state to assess every mile of roadside. Some roadsides will lend themselves to tallgrass prairie plants and a wide assortment of forbs. Other stretches may serve as linear wetlands. The goal should be to populate as many of our roadsides as possible with native plants that once covered all of Iowa. Think carbon sequestration. SWAPA? Certainly.

One of my favorite governors was Robert Ray. Many Iowans today still admire the support he gave to establish our bottle bill and are proud of Iowa’s efforts to keep our roadsides clean. Just think: perhaps someday Iowans will boast about their roadsides being beautiful as well. If Robert Ray were still alive, I’m sure he would smile.

Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture

Iowa established the Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture at ISU as part of our Groundwater Protection Act in 1987. Supporters of an industrial model of agriculture (as opposed to our traditional family farm model) tried to stop us from establishing the center and have tried to weaken it ever since. I’ll never understand why they are doing this. It seems so small. Some fertilizer and pesticide dealers also opposed the center, saying we were trying to start an organic farming center.

After 30 years and over 600 science-based research projects sponsored by the Leopold Center, politics changed in the Iowa House and Senate and they passed legislation to functionally abolish the center.

Unfortunately, many of our commodity groups and the Iowa Farm Bureau chose to remain neutral. (Sins of omission?) Rich Rominger, the deputy secretary of our U.S. Department of Agriculture when I served as Chief of SCS/NRCS, recently sent me an announcement that his family farm in California was named the Leopold Conservation Farm of the year in that state. The California Farm Bureau gives that award every year, in partnership with the Sand County Foundation, and the California Sustainable Conservation organization.

Oh, how I wish that the Iowa Farm Bureau would be more supportive of the Leopold Center. Although Governor Terry Branstad allowed the Leopold Center funding to go elsewhere, fortunately he vetoed the effort to wipe the enabling legislation from the state code. The Leopold Center still exists, waiting for the Iowa legislature to correct its mistake and fund it again.

It was Leopold Center funded research that has boosted our understanding of the science of vegetative buffers along rivers and streams, science that is recognized worldwide today. It was policy developed with funding from the Leopold Center that brought a flourish of farmer’s markets to Iowa communities over the last decade. It was on-farm research with Leopold Center funding done by many members of the Practical Farmers of Iowa that perfected alternative ways of growing animals and crops in our state.

The Leopold Center is not an organic farming center, but it is not afraid of organic farming. And it has supported research that demonstrates ways in which we can use pesticides and fertilizers more judiciously.

I’ve been told that more than 60 Iowa professors have taken advantage of Leopold Center funding in their teaching, research and graduate student support. Graduate students from Iowa State have received funding over the years from the Leopold Center, and today their efforts to encourage more sustainable agriculture are recognized worldwide. Also, many land grant universities in other states have now developed centers like the Leopold Center. Scientists at those institutions and around the world are scratching their heads wondering what is going on in the state of Iowa that they would let this great program die.

Aldo Leopold is considered the father of the land ethic which encourages us to be part of the larger life community. He said,

The land ethic simply enlarges the boundaries of the community to include soils, waters, plants, and animals, or collectively: the land … [A] land ethic changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land-community to plain member and citizen of it. It implies respect for his fellow-members, and also respect for the community as such.

And further, “A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.”

Iowa’s annual budget is over $8 billion. The Leopold Center funding share was $1.5 million. It’s time that we restore that funding. Supporting research on SWAPA? Makes sense.

Further thoughts

Implementing the above suggestions for Iowa agriculture and land use, coupled with our wind and solar energy production and greater emphasis on energy efficiency, could make Iowa carbon neutral. But I think Iowa agriculture can contribute more. Why not be bold. Here are two more “intentionally naïve” ideas:

1. Let’s open up our utility laws and encourage farmers to establish solar farms in which urban folks can purchase ownership and be credited each month for what their panels produce (net metering). Very soon Iowans will be transitioning to electric vehicles. There will be a huge demand for electricity at that time. We have an opportunity right now to add some distributive electric power generation. Talk about a third crop and diversifying agriculture! It would be great if Iowa farmers provided the foundation for this transition. Go home Koch brothers and let Iowa be Iowa.

2. I’ve always been intrigued by the area in north central Iowa defined as the Des Moines lobe. This area once contained more than three million acres of wetlands. Through amazing ag engineering we drained those wetlands. In doing so, we converted what was called “wasteland” into some of the most productive agriculture land in the world. But now we understand the harm that we are doing a thousand miles away in the Gulf of Mexico.

Let’s challenge our agriculture research to redesign drainage in the Des Moines lobe into a water management area. We have hundreds, perhaps thousands, of wet areas in our present drainage that are probably not farmable at least three in ten years. We could modify the drainage system by repopulating these potholes with native wetland species and manage them to hold back water and let plants absorb excess nitrogen. These potholes today contribute nitrates over and above what we apply in agriculture because soil in them is so rich in natural nitrogen. By replanting native species into them, we would not only manage our drainage system nitrates, but also the nitrates that come from our Iowa soils.

Conclusion

The practices suggested in this paper would turn Iowa agriculture into a positive force on climate change. Perhaps we could become the first state in the country, and the only agriculture state, that is carbon neutral. In fact, Iowa might even become the first state that actually sequesters carbon rather than releasing it. These practices would also result in Iowa farms that are more multi-functional, and thus healthier and more sustainable.

In agriculture we often deny that we have a problem, then we delay in fixing it, but through our land grant and other universities and innovative Iowa farmers we bring amazing science to agriculture. I find it reassuring that many farmers in Iowa are already applying some of these practices and are constantly coming up with ideas to make them work even better. I’m convinced that we can use Nature’s services to solve many of our agriculture pollution problems and global climate issues if we put our minds to it. Let’s stop denying and stop delaying. We can do it.

Robert Frost in his poem Mending Wall speaks of walls with the words “Good fences make good neighbors.” Frost was speaking about rock walls in his poem. Many of the practices in this paper refer to utilizing native plants as walls and fences. They help to make good neighbors between different uses of land on the farm. And because they add multiple functions, they make good neighbors between agriculture and the rest of society as well.

Americans are now focused on the Coronavirus pandemic. This is as it should be, but we must not forget that human induced climate change will still be our major concern long after we’ve conquered Covid-19. We need to implement the practices I’ve outlined. And we should not stop working on the other functions that these practices also address – soil health, clean water and air, diversity in plants and animals (SWAPA). You, the reader, may have other ideas. It’s time you make your voice heard. There are truths yet to be learned and understood.

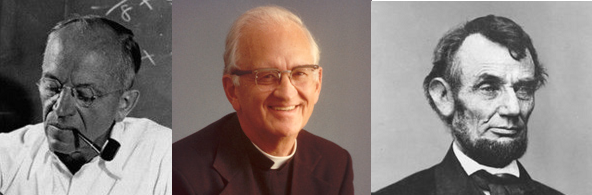

All of us need to keep in mind the advice of Bishop Maurice Dingman and Abraham Lincoln: avoid sins of omission and always do what is morally right. Also let us continue to cultivate Aldo Leopold’s land ethic. Rest in peace Maurice, Abraham, and Aldo.

Paul W. Johnson

Decorah, Iowa

Top image: From left, Aldo Leopold, Bishop Maurice Dingman, and Abraham Lincoln.

2 Comments

Excellent ideas, and thank you! Here are two more...

1) Scrap and rewrite Iowa drainage law. The law is a century-old embarrassment that starts out by essentially declaring “Water is our enemy!” It goes downhill from there, and is bad for water quality, soil, biodiversity, and even property rights.

Some local officials who want to reduce water pollution are finding Iowa drainage law to be a serious obstacle. It’s time for the Legislature to stop treating drainage law as sacred and to drag the law and its defenders, screaming and kicking and all, into the modern era.

2) Officially encourage the use of Iowa-origin prairie seed for Iowa prairie plantings, and ask the NRCS to do the same. The DNR has the right idea — the agency raises and plants prairie seeds descended from Iowa prairie remnants, which evolved to fit Iowa conditions and Iowa pollinators, for use on DNR land.

Certain Iowa commercial growers do the same, but a lot of Iowa CRP plantings have used prairie seed with distant genetic origins, ranging from Texas to Ontario, bought from distant growers. As the demand for prairie seed increases in rural and urban Iowa, Iowa businesses should be raising and selling Iowa-genetic prairie seed and keeping the profits here.

PrairieFan Fri 4 Sep 9:47 PM

Real community health

While we are talking land and community health please consider taking land which is flooded on average every 5 years along with steep slopes over 9 percent and allow them to be restored and rewilded to natural habitat. These areas could still be used for gazing, recreation, perennial crops, growing trees and nut harvesting in addition to providing wildlife corridors and suitable habitat for the other creatures trying to maintain in this state known as the most biologically altered state in North America with roughly 98% altered for human use. These areas of flooding and steep slopes which are not economically viable now would amount to one-fourth of Iowa. This would quickly address erosion, water quality issues, biodiversity, and community health in just a few years.

Mark Edwards Tue 8 Sep 5:23 PM