John Whiston contrasts two strains of American populism and ponders how a populist agenda could unite diverse Democratic constituencies.-promoted by Laura Belin

You hear a lot of anxiety these days about the rising tide of “right-wing populism.” How in God’s name did Donald Trump increase his share of the vote in localities like Lee and Clinton counties in Iowa and Kenosha and Dunn ounties in Wisconsin? So, maybe it’s time to take a step back and think about what “populism” really means – today, historically, and for the American future.

Today, on one hand, we have strong performances by Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren in the Democratic primaries,running on overtly populist programs of fighting economic inequality and corporate control of government on all levels. On the other, there’s Trump consistently attacking “elites,” and increasing his share of the vote from the white lower middle class.

And the trend extends beyond the election. A December 1 Washington Post editorial tabbed the anti-elite posturing of Republican Senator Josh Hawley of Missouri as “what GOP politics after Trump will look like.”

Many commentators have remarked that the entire election process had a populist taste, but in their rush to emphasize both-sides-now, they have missed the crucial truth. Populism in the United States has always existed in two very different flavors – Left and Right. Their superficial appeals, “it’s us little folks against the elites,” sound the same, but their histories, their underlying theories, their organizing principles, and their leaderships are drastically different. And most importantly at this juncture, their prescriptions for how the country might respond to existential challenges involving class, race and democracy are radically different.

In sum then, I hope to convince you that the right-wing version has no theory and no principles. It cynically obscures who those elites might be and, in the end, it can only lead to division and despair. The left-wing version, on the other hand, has defined principles and a moral appeal to our better nature. If conscientiously developed, it offers both the Democratic Party and the nation as a whole a pathway to a more just and sustainable future.

EARLY LEFT-WING POPULISM

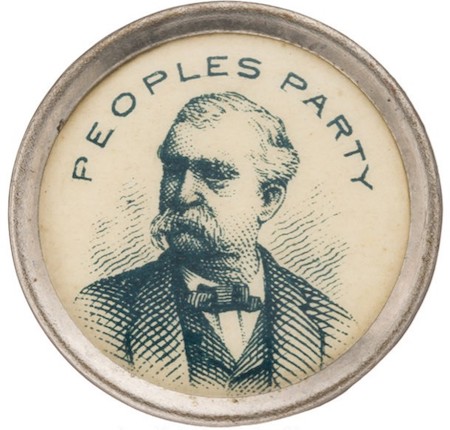

A brief introduction to American Populism might help. The first use of the actual word occurred in 1891 to describe the emerging Peoples’ Party, and the party very quickly took to it. That Populist Party began as an agrarian protest rooted in the Farmers’ Alliance/ Grange movements but it soon attracted support from leaders of early labor unions like Eugene Debs (American Railway Union) and Terrence Powderly (Knights of Labor). The newly born party first met in Omaha in 1892 and nominated James B. Weaver, a former member of Congress from Iowa, for President.

The tone was something that even today we would recognize as “Populist.” Weaver castigated “the few haughty millionaires who are gathering up the riches of the new world.” The platform adopted was a prototypical left-wing populist document. “The fruits of the toil of millions are baldly stolen to build up fortunes for a few, unprecedented in the history of mankind; and the possession of these, in turn despise the Republic and endanger liberty.”

To correct this oppression, the party proposed that the power of government be expanded to adopt a series of class-based reforms: promotion of labor unions, public ownership of the railroad and telephone industries, ending subsidies or other national aid to private corporations, anti-monopoly legislation, limitations on speculative ownership of agricultural land and a progressive income tax.

The party also worked for a series of democratic reforms to blunt oligarchical control of government, for instance, women’s suffrage and direct election of senators. In sum, “we seek to restore the government of the Republic to the hands of the ‘plain people’ with which class it originated.”

The newly-minted Populists carried five states in 1892, including Kansas and North Dakota, but curiously only got 5 percent of the vote in Iowa. The Party itself was short-lived, quickly torn apart by the question of whether to align with the Democrats, the rising Socialists, and even the then-influential progressive Republicans. The momentum of the movement, the class-based appeal, the grassroots organizing, and the emotional fire, however, endured in the progressive movement, the New Deal, the civil rights movement and in the recent campaigns of Sanders and Warren.

We need to remember several important traits of this left-wing populism, at its origin and throughout its later manifestations. First, the critique was applied to a “system.” It spoke passionately about the moral dimensions of what was wrong with that system.

Populists, moreover, came to a generally accepted explanation of how that capitalist system functioned. This explanation was class-based, but on a very precise basis. The subject class, the farmers or the laborers, the plain people, suffered as a class and their oppression took the form of real economic and political loss. Wages stagnated, farm prices declined and transportation costs skyrocketed, education became less accessible, medical care led to bankruptcy. Unions were broken; their political impact was cut off at the knees by the economic power of the millionaires. Families fell apart and people died.

Secondly, the “elite” also came to be precisely defined. It was the “millionaires” who owned the great enterprises of this country.They as a whole were the problem. While certain actors, like railroad tycoons, might be more objectionable, it was the entire system with its dramatic differences in wealth that generated the trials of the plain people and the wantonness of the elite.

These populists, of course, directed their anger also at political leaders, for instance the various state railroad commissions, because they operated as tools of the millionaire class. In the same way, newspapers were disparaged for their slavish adherence to the gospel and agenda of wealth. Yes, they stereotyped the ruling class. There are lots of cartoons of millionaires looking like the Monopoly Man or Scrooge McDuck. They personalized the system by attacking specific capitalists like J.P. Morgan. But the Populist impulse at its best was not an emotional response to their supposed contempt for the rest of us. It saw systemic failures and demanded systemic reforms.

EARLY RIGHT-WING POPULISM

The success of this original populism brought hostility, rivalry, and imitation. By the 1920s, you see right-wing movements that borrow the language and fire of the populists. The Second (Northern) Wave of the Ku Klux Klan raged against liberal and intellectual elites, often alleged to be Jewish, who promoted integration. But it was almost a cynical afterthought to their emphasis on white supremacy. Various radio personalities like Father Coughlin and later Rev. Carl McIntyre preached against terrifying but hidden elites who would rob the common folks of their birthright.

Americans, for the most part, were spared the full force of right-wing populism, not so for Germans, Italians, and others. The Nazis did, for a time, demonize a portion of the capitalist class as a cynical excuse for their murder of Jews, Gypsies, leftists, and the disabled.

This worldwide rightist flowering, along with the left-wing experience in the Soviet Union, soured many on the entire concept. Moderate, good government people were horrified that it raised up demagogues, who became tyrants. They distrusted the emotional tone and pulled away from any systemic critique. In academia, led by Richard Hofstadter, the emphasis shifted almost entirely to a critique of populism generally.

THE POPULIST INFLUENCE ON REPUBLICANS

After World War II, the left-wing version did retain some awkward vitality as part of the established New Deal coalition. But the right-wing version became an increasingly influential part of the Republican Party. A long line of conservatives like Joe McCarthy, Spiro Agnew, Ronald Reagan, and Pat Buchanan would play to the masses by taking on amorphous elites.

Only with the Tea Party and its illegitimate child Donald Trump, however, did the trend reach a tipping point by actually generating substantial electoral gains. Trump was coy about how to pitch it: “media elites,” “political elites,” “the elites who only want to raise money for global corporations.” In one speech to coal miners in Pennsylvania, he claimed that only he could identify the culprits because “I used to be part of them. Hate to say it.”

Post-Trump Republicans have already begun the project to deepen and broaden the draw. Senators Marco Rubio of Florida and Hawley are at the forefront. Hawley is lesser-known but has gone further in publicizing an actual theory that might support an appeal to a broader audience. In a 2019 speech to the National Conservativism Conference he said, “No,the great divide of our time is between the political agenda of the leadership elite and the great and broad middle of our society.”

For our purposes here, it’s also notable that Hawley defined this elite as powerful upper-class managers who “run businesses and oversee universities here but their primary loyalty is to the global community.” In sum, “call it the cosmopolitan consensus.”

Conservative media has been pumping out a similar amorphous narrative. Tucker Carlson said in a 2019 interview with Vox, “So, I’m concerned about Bernie Sanders, but his basic critique that the system is rigged on the behalf of a small number of people, it’s totally true.” To his mind, an elite upper class set of financial managers are gutting the American economy in aid of a globalist strategy and in turn destroying the American family.

A COHERENT MODEL VS. A MISH-MASH

So, what do we make of this over-long history lesson? How does our current form of right-wing populism differ from its older left-wing model? Well, for starters, if you are buying a used car, you have to listen very carefully to the salesman’s pitch. The exaggerations and the gaps in the repair history will tell you a lot more than the emotionally charged spin on how dashing you will look behind the wheel.

What distinguishes the two models more than anything is that the left-wing one has a coherent explanation about how the system works: a theory, if you will, of who constitutes the elite and how they maintain their power and how the people suffer from that power. The right-wing model has no coherent theory but muddles everything to obscure first, the identity of those in control and second, the mechanisms of control.

The basic Republican model does not say that the elite is any identifiable group. It is a mish-mash depending on the audience. Somedays it’s the media, somedays Hollywood, somedays politicians, other days venture capitalists, somedays intellectuals, and somedays just wealthy judgmental do-gooder types.

This is not by accident. In pre-World War I Germany, the Social Democratic Party (SPD) had to deal with opponents, proto-Nazis in many ways, who in an attempt to entice working class voters away from the Socialists would rage against various elites, often because those were “cosmopolitan” and Jewish. August Bebel, chairman of the SPD, is quoted as saying the following (loosely translated) to explain the phenomenon: “Antisemitism is the Socialism of ignorant dudes (dummen kerle). ”

Well, Right-Wing Populism is sold as a socialism of ignorance. The manly white paint job on one’s pickup advertises the us-versus-them message but hides a rusted-out frame and a four cylinder engine running on incoherent resentment. If there are any number of elites responsible for the perceived slights, there is no need to dig any deeper to find and articulate a basis for your response.

Resentment does not lend itself to generating a reform program that actually alters the system, that actually changes the structures through which a real elite functions, that actually alters the economic incentives that channel the system. So, the current conservative form advocates no reforms, no change in rules or regulations, no alteration in the economic calculation. No, the only reformation is the shaming demand that the elite somehow do it differently.

It’s much easier and, in a way, so much more satisfying to caricature the object of your grievance. The elitists are to be condemned not for the effect that their actions have on people but because their motives are so plainly perverse. They are greedy cosmopolitan globalists. And they are so plainly not at all like us culturally; pick a stereotype to fit the elite-of-the-day: secular, over-educated, Wall Street, Washington, coastal, effete, brie-eating, and most of all, judgmental. And if someone were to interpret all this as an implicit condemnation of Jews, well, nobody said anything like that.

Hawley and Carlson are trying to construct a plausible narrower classification, but it suffers from many of the same problems. The class enemy is the management of the financial system, so they say. Their manipulation of the flow of capital resulted in the closing of so many workplaces. Carlson is particularly fond of how little Sidney, Nebraska, lost the headquarters of the locally-founded Cabela’s sporting goods chain due to the machinations of these “vulture capitalists.” Trump and a hundred Republican office-seekers have raised the specter of calculated closings throughout coal county in Pennsylvania and Wyoming.

Yes, there is some truth in this. But laying all the responsibility on the financial sector masks the participation of other sectors. What about the owners of Cabela’s and the rest of the retail industry like the Walton family? What about the owners of the coal mines like Don Blankenship, convicted of felony violation of safety standards? Or the rest of the extraction industry, like the Koch family (oil and timber) and Harold Hamm (the founder of Continental Resources which developed the Bakken in North Dakota)? What about the food industry, the Tyson empire, for instance? Or Agribusiness?

The awful truth hiding behind this silence is that all of those oligarchs are major powers and contributors in the GOP.

There is real pain and loss when jobs disappear, but campaigning only against that event masks the many related abuses. The real issues are broader and deeper. Health care–right-wing populism has concluded that it is not an issue. Wealth disparity, minimum wage–ditto. Wage theft, temp agencies. Regressive tax system. Education, primary, secondary or later. No, right-wing populism, by design, has structured its critique to illuminate neither the fundamental structures of our economy nor the real problems of its intended audience.

CHALLENGES FACING DEMOCRATS

The old left populism grew through local organizing at the Grange hall, the state Farmers’ Union or your union local. As those institutions have faded, it has primarily tried to communicate through Democratic electoral campaigns. Recently, the content even of those appeals has paled.

Take, for instance, the Democratic election ads in Iowa in 2020. Much video of convivial candidates in flannel shirts standing in front of tractors, but very little about the specific challenges rural and working class people face or specific populist initiatives that the supposed Blue Wave might produce. Biden did issue an exhaustive “rural plan,” but it slighted populist policies. For instance, antitrust enforcement came in as the 35th bullet point. And even that plan could barely have been noticed for all the anti-Trump content in the campaign.

Historically, conservative movements have relied on mass media. Father Coughlin was the grandfather of Tucker Carlson and FOX News. Even the Tea Party eruption of 2010, the best local organizing the right-wing has ever done, was a charade funded by billionaires and ginned up by media voices.

The conservative model by necessity raises up deeply flawed demagogues. If there is indeed no basic theory for the undertaking, then there are no constraints on what the leadership can do. If the undertaking is fundamentally premised on a cynical charade, then dishonest cynics rise to the top. So, we see the right-wing model being led by Joe McCarthy, Spiro Agnew and Donald Trump. The old left populism raised up inspiring honest leaders who emphasized the moral dimensions of the movement. Compare this from Eugene Debs: “I would not be a Moses to lead you into the Promised Land, because if I could lead you into it, someone else could lead you out it.”

The leading right-wing populists then are peddling high sugar baby food to satisfy, for the moment, widespread anxieties in their audience. I will be the first to admit that this approach has a powerful draw, especially in the last election. So, why is that?

In the briefest form, because the Democrats in general have lost track of how to post a viable populist alternative and communicate it directly to the intended audience. They have ceded the playing field to the Right. And the strength and virulence of the result must prompt a thorough-going reexamination.

The Democratic Party has found itself between a rock and a hard place, between the critique articulated by Sanders and Warren and its history of accommodating the very elites that Sanders and Warren are condemning. Politico has just published “Why Democrats Keep Losing Rural Counties Like Mine,” a very wise essay by Bill Hogseth, a Farmers’ Union organizer and chair of the Dunn County, Wisconsin, Democratic Party. Hogseth says that the actual treatment of rural areas by the national Democratic powers has for years been quite unpopulist.

For instance, the Obama Administration refused to enforce “country of origin” labelling requirements and accommodated monopolistic trends in the industry such as with the Kraft-Heinz and JBS-Cargill mergers. How do you admit that the party in the past has been guilty of corporatist policies and contained a slice of that corporate elite, but claim that we will now fight for a quite different goal? Navigating this contradiction would take a great deal of nuanced thought and political courage; cheery smiles without a precise program will not do the job.

The Democratic Party also finds itself between a rock and a hard place on the issue of race. Left-wing populism has always had a weak link on this issue. The very first Populist platform, which I described earlier, contained an anti-immigrant plank. Even the most progressive unions in the early twentieth century struggled with including African Americans. And, truth be told, the historical constituencies for a left-wing populism, rural and working class White Americans, still retain vestiges of racism. Maybe not the explicit racism that is so toxic among Republicans, but at least some amount of implicit bias and a blind spot about systemic racism. As do we all.

The difficult thing about implicit thought processes is that we are not aware of them. We just go ahead and make the unconscious association between the current stimulus and our baked-in assumptions about the nature of African Americans. Our most current events can quite easily trigger those associations for this old populist demographic.

For instance, the Black Lives Matter Movement. Early on, after the murder of George Floyd, polls showed support for BLM close to 70 percent. The demonstrations, though, became more frequent and to some degree more disorderly, the rhetoric came more to reflect identity politics and the demands turned to “Defund the Police.” Later polls showed approval of BLM sinking to around 40 percent. I strongly suspect that much of the movement to Trump in Iowa and Wisconsin was a response to those developments.

A WAY FORWARD

The Democrats don’t have much room to move at the corner of Rock Road and Hard Place. Black voters are the reason Joe Biden will be our president so they and their leaders will be looking for acknowledgement of that fact. Party leaders will have to put real effort into generating a nuanced explanation of how meeting those expectations can meld with a specific populist program that draws in white rural and working class people. As a starter, it should recognize that African Americans, especially in the South, are quite used to a populist approach and a moral appeal. See, for instance, the Poor Peoples’ Campaign led by Rev. William Barber.

Many claim that such a coalition is impossible. I heard an African-American academic on the radio argue that the party should abandon any effort to assuage the “feelings” of the white working class. I saw a conservative commentator on TV crowing that the GOP is now the white working class party.

It is, however, still worth the effort for more than moral reasons. There is little hope of any progressive advances in the upper Midwest without it. Even nationally, the frighteningly small margin against an incompetent narcissist must make us ask where there might be viable coalitions for the future.

Now, I am not smart or ambitious enough to lay out what the left-wing populist program might look like. Rather, I would suggest that the party start with the work already done by Senators Sanders and Warren and Rev. Barber emphasizing wealth disparities. A platform that offers precise reforms in tax policy, antitrust, education, racial justice, and labor union policy would go a long way toward creating a principled narrative which reaches across much of what currently divides us. Bill Hogseth wrote something similar from Dunn County:

For Democrats to start telling a story that resonates, they need to show a willingness to fight for rural people, and not just by proposing a “rural plan” or showing up on a farm for a photo op. Rural people understand economic power and the grip it has on lawmakers. We know reform won’t be easy. A big step forward for Democrats would be to champion antitrust enforcement and challenge the anticompetitive practices of the gigantic agribusiness firms that squeeze our communities.

In the meantime, while organized Democrats struggle to bridge these chasms, we all have important work to do. It is necessary to engage with the resurgent right-wing populist narrative by challenging its credibility at every turn. Its history and theoretical structure will lead anyone to acknowledge its weakest points.

So, at each of our opportunities to say so, in small COVID-safe groups, with coffee mates, and at the Zoom holiday gathering with Uncle Ralph, we have to acknowledge its understandable allure but stubbornly proclaim its fundamental dishonesty.

John Whiston is a retired lawyer and law professor in Iowa City.

Top image: Campaign button for James Weaver’s 1892 presidential campaign, available via Wikimedia Commons.