Dan Piller reviews presidential attitudes toward public health and physical fitness.

If you needed a good laugh during the hassle of Christmas weekend, one could be had by watching the sudden fracture of Donald Trump and the nation’s anti-vaccine cult. This surprising development came about during a Trump podcast interview with Candace Owens, for whom no conspiracy theory is too outrageous.

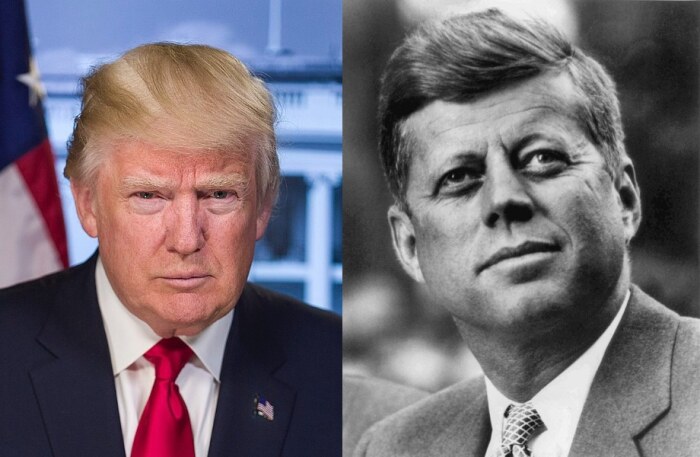

Trump and Owens should have enjoyed a convivial chit-chat, but the former president took issue with Owens’ anti-vaccine sentiments. Trump’s Operation Warp Speed initiative to give us COVID-19 vaccines was arguably the highlight of his otherwise inept presidency. Even President Joe Biden has praised it.

Owens uncharitably attributed Trump’s pro-vaccine sentiment to his being “too old” to find websites that give alternatives to vaccinations, which probably will prove sufficient for her to be turned away for good at the Mar-a-Lago main gate.

Anti-vaccine sentiment is arguably a public health threat even bigger than the COVID-19 pandemic, since it also can cover inoculations against the conventional annual influenzas, not to mention protections needed for schoolkids of various ages against childhood diseases as well as polio and meningitis. Anti-vaxxing is a fairly new phenomenon. George Washington famously ordered all his troops inoculated against smallpox during the American Revolution. In 1955 there was scarcely a peep of protest when kids were marched into school cafeterias to receive the Salk vaccine, which almost overnight ended the polio epidemic that terrorized American parents during the first half of the decade.

But at this writing, just 62 percent of Americans are fully vaccinated against COVID-19 despite pleas from the White House, the Centers for Disease Control, and numerous physicians, scientists, medical administrators and celebrities. As a result, the year 2021 is ending not with the expected victory over coronavirus, but with overflowing hospitals and cancelled airline flights and sporting events.

Resistance to health warnings is thought to be another libertarian impulse. But it can also be seen as connected to Americans’ touchiness about their weight, which predates this pandemic. Michelle Obama’s White House vegetable garden was a well-meaning effort to improve kids’ diets overladen with excesses of junk food. The First Lady’s garden initiative drew opposition from agriciulture and food processing interests, but also tripped over Americans’ obsessive sensitivity about their weight. Since 70 percent of Americans are overweight and 40 percent are obese, a rate public health experts describe as an epidemic, any politician who can read a poll knows better than to public suggest that Americans eat healthier and exercise more.

But as the novel coronavirus invaded America and attacked the lungs of its victims, it proved particularly harsh on overweight folks who already struggle with breathing issues. Even so, Americans don’t want to hear obesity-related health warnings, and political leaders are reluctant to speak up.

It was not always so. During the last week of 1960, subscribers to Sports Illustrated magazine (which fulfilled the role for sports fans that cable television’s ESPN does today) featured a color photo of President-Elect John F. Kennedy and wife Jackie in full youthful trim, on their sailing boat. The cover touted a piece inside authored by JFK himself entitled “The Soft American.” Using words that would be considered fat-shaming today, the incoming president lamented that one-third of young men annually were rejected for military service, mostly for overweight. American kids lagged in physical fitness tests against their peers in Europe and, most ominously, the Soviet Union.

“Physical fitness is the basis for dynamic and creative intellectual activity,” the president-elect wrote. “but the harsh fact of the matter is that there is an increasing number of young Americans who are neglecting their bodies – becoming soft.”

Most presciently, Kennedy warned that poor health and fitness in the general population would lead to rising health care expenses.

Kennedy’s predecessor, Dwight D. Eisenhower, had sounded the alarm first. The old general, too, was worried about the high rejection rates by the Selective Service. But Ike, who turned 70 the year his second term ended, wasn’t in a position to personally advocate greater physical exertion due to a heart attack, stroke, and major intestinal dysfunction during the last five years of his presidency.

JFK, who at 43 was the youngest man ever elected president, was not so constrained and he became a frequent champion of more “vigor” in physical activity. America’s schoolkids were subjected to regular physical fitness tests and the 50-mile walk became a symbol of the Kennedy administration.

The new president appeared right for the role of exercise-leader-in-chief, with a slim build, tapered by swimming and tailored Brooks Brothers suits. Unknown to the public at the time, JFK suffered from Addison’s Disease, which actually made it hard for him to gain weight. The president treated that problem by becoming a juicer—a user of steroid-based medications—several decades before athletes discovered their benefits.

Kennedy turned Eisenhower’s Council on Physical Fitness into a major platform to campaign for greater fitness and spoke out regularly on the subject. In 1962 he used a speech at the presentation of the Heisman Trophy to the nation’s top college football player to urge Americans to quit being spectators, get out of the grandstands and get more exercise. JFK’s early form of fat-shaming apparently didn’t hurt him politically. He maintained favorable polling margins in the 60-75 percent range, well in excess of what presidents can achieve today.

Any momentum to turn the U.S. into a more physically fit nation died with Kennedy in Dallas. In 1963 about 25 percent of Americans were overweight, a number that would triple in the next half-century. More alarming, the rate of obesity climbed from 5 to 7 percent in the early 1960s to more than 40 percent today. The usual culprits for this lamentable state of affairs are fattening fast and processed food, lack of time for exercise, and the convenience of modern life. The advent of Amazon-led internet home shopping removed many Americans’ lone exercise, walking at the shopping mall.

Kennedy’s test-driven push for better fitness may have backfired. Today, credible figures show that less than 20 percent of Americans patronize the various health and workout centers prevalent even in small towns, and Americans cite ridicule in phys ed classes by fellow students and bullying P.E. teachers as a reason for their aversion to working out in gyms.

JFK’s successor, Lyndon Johnson, was a bulky Texan who wasn’t about to give up his barbeque, Mexican food, and ice cream. He didn’t bother to reduce a prominent paunch during his White House years. Subsequent presidents contented themselves with leading by example, with scant results. Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford proved cautionary examples to future presidents to be careful about publicly engaging in sports of skill. Nixon’s attempt to be a regular guy on the White House bowling alley showed a hopelessly awkward effort. Ford, who had been an All-American football player in his college years, generated ridicule by bonking a spectator with an errant drive at a golf tournament and falling down the steps of an airplane ramp.

By the late 1970s the U.S was in a boom in recreational running, inspired not by JFK but by marathoner Frank Shorter’s victory at the 1972 Olympics. Jimmy Carter was a runner, but a fainting spell during a run in 1979 only accelerated the Georgian’s decline in public esteem as the American economy went south.

Ronald Reagan still had an older version of his Hollywood leading man build, which he reinforced with daily workouts. But the Gipper came from an era when working out was considered an eccentricity and stars didn’t publicize their exercise routines, preferring for audiences to believe that their good looks came naturally. Reagan’s White House put out the story that he kept in shape by clearing brush on his ranch.

George H.W. Bush exercised and was frequently photographed playing golf, tennis, pitching horseshoes, and piloting his boat. But like his most recent predecessors, Bush didn’t urge Americans to do likewise. Bill Clinton, a JFK worshipper, might have been expected to pick up the role from his hero and reignite the physical fitness crusade. But while Clinton ran regularly to fight a weight problem he, too, saw the evolving majority of overweight Americans and didn’t make public health an issue. Neither did George W. Bush or Barack Obama, Michelle’s White House garden notwithstanding.

It was left to Donald Trump, whose electoral strength came in the South and Midwest where obesity rates are the highest, to articulate sentiment against exercise. Trump disdained workouts, saying they sapped precious energy (health experts say otherwise) and argued that he got all the exercise he needed with a weekly golf game while riding in a cart. Even devoted golfers laughed at that howler. When Trump’s physical exams showed he was at least borderline obese, news coverage was hit by blowback from the “body positivity” advocates for the overweight who declared such reporting was harmful to the psyches of Americans who struggle with the shame and discrimination traditionally visited upon the overweight.

More damaging, Trump turned loose his ideological wolfpack on Dr. Anthony Fauci and other public health officials who saw their appeals for masks, vaccinations, and more responsible family gatherings drowned in a flood of internet-fed paranoia and conspiracy lunacy. After being pummeled simply for urging mask-wearing, Fauci could be excused if he passed on saying anything about connections between America’s rates of obesity and high intensive care admissions.

JFK would be amazed.

Dan Piller was a business reporter for more than four decades, working for the Des Moines Register and the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. He covered the oil and gas industry while in Texas and was the Register’s agriculture reporter before his retirement in 2013. He lives in Ankeny.