This column by Daniel G. Clark about Alexander Clark (1826-1891) first appeared in the Muscatine Journal.

Back to the story of Jim White and the slave catcher at Bloomington, Iowa—now Muscatine—in 1848.

It’s a story I started telling about 20 years ago, relying on the version told a century after the events by “well known attorney and raconteur” William D. Randall (as he was described in the Muscatine Journal, where he was once the city editor).

My first tellings were a trolley-tour narration in which my Alexander Clark bit was brief and entertaining. I told my riders that Clark helped free “Jimmy,” then recruited Black soldiers for the Civil War and integrated Iowa schools and got famous as an orator and ended up as ambassador to Liberia.

That’s more or less the condensed biography I knew and presented at the 2007 Iowa Underground Railroad conference I attended with Kent Sissel. And I read from Randall’s “Jimmy White Finds Freedom!” (Little Known Stories of Muscatine, 1949.) Long story short, I got some expert feedback and started going deeper into Clark’s life and context, first in Robert Dykstra’s Bright Radical Star, which I’ve mentioned before.

Dykstra tells the Jim White drama well, and so have several other authors, but my favorite version now is in a 2013 book by Lowell Soike, titled Necessary Courage: Iowa’s Underground Railroad in the Struggle Against Slavery.

Soike had been Dykstra’s graduate student, and he was the staff historian at the State Historical Society of Iowa who headed up the society’s Underground Railroad documentation project. The conference was part of that. I learned that Kent had known Lowell a long time.

Soike’s writing is careful and complete. His Jim White chapter conveys the details and nuances, such as they can be known now.

In a previous column I presented J.P. Walton’s account of the arrests of both the freedom seeker and his pursuer; a telling that features Supreme Court Justice S.C. Hastings as the judge who freed Jim White. Then I told of recent revelations about Hastings that take the shine off his part in the story.

Now I turn to the other judge: Bloomington’s justice of the peace, whose ruling Hastings upheld. David “D.C.” Cloud was 31, admitted to the bar in 1846 after studying law five years while working as a carpenter. His wife died in 1846, soon after giving birth to their third child. None their three children had lived, and so he was living alone when the Missouri slave catcher Horace Freeman came to town demanding Jim’s arrest.

It was the young magistrate’s first slave-related case. Both sides had big-deal lawyers.

Soike:

Word of Jim’s arrest spread quickly, causing considerable public excitement. The next morning, crowding into Cloud’s twenty-by-twenty-six-foot office were as many people as could fit. Many, Cloud remembered, were there not so much to listen as to ‘take sides for or against “Jim.” The [Freeman] trial took two days, and each day at noon and in the evening, proslavery and antislavery friends constantly buttonholed Cloud to persuade him one way or the other. One friend awakened Cloud (a widower who slept in a room adjoining his office) by rapping at his door at midnight. The man [“a friend from Old Virginia”], asked where the situation stood, and they discussed the matter briefly. Then, turning to leave, he urged Cloud to find that ‘that [N-word] is as much property as a hoss, and I hope you will not deprive the owner of his property.’ And hardly had Cloud left his room the next morning when he ‘was almost besieged by the friends of Jim.’

One of Soike’s sources is a letter Cloud wrote in 1897 to the editor of The Annals of Iowa, wherein he expounds on his abhorrence of slavery, dating from boyhood in Ohio. And then this: “Whatever may have been my personal feelings on the questions, I determined to try the whole matter according to law and evidence. The trial of the two cases lasted three days.”

Judge Cloud moved carefully. In the end, he decided he had to rely on a single precedent concerning an enslaved man named Ralph in 1839. It was the very first decision by the supreme court of the Iowa Territory.

“Taking that as the law of Iowa, I decided. First, that Jim was a free man, and second that Freeman was guilty of assault and battery.”

He fined Freeman $20 (which would be worth $728 in 2022 dollars) and court costs. His friend from Virginia paid the bill.

My favorite editorializing from the newspaper report: “There is no such an animal in the town of Bloomington as an abolitionist. But there are men here who will not see injustice done to any man black or white, and those, too, who are not willing to see shackles placed upon the legs of any one whom the law makes free.” (“The Negro Case” Bloomington Herald, October 18, 1848)

Next time: The “d—d Yankee Church.”

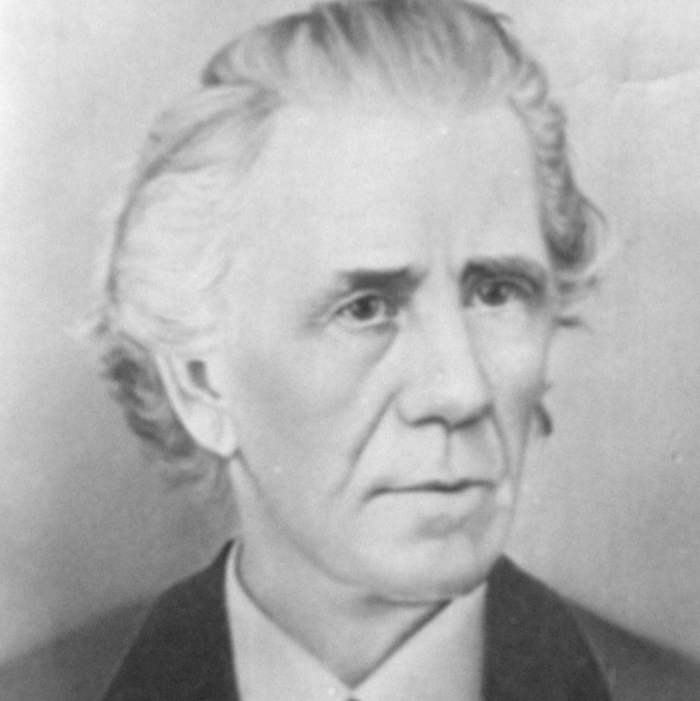

Top image: David C. Cloud’s official photo from the Iowa legislature’s website.