Bruce Morrison is a working artist and photographer living with his wife Georgeann in rural southeast O’Brien County, Iowa. Bruce works from his studio/gallery–a renovated late 1920s brooding house/sheep barn. You can follow Morrison on his artist blog, Prairie Hill Farm Studio, or visit his website at Morrison’s studio.

Every summer we enjoy the monarch butterflies in our pastures and acreage, from their first arrival to their final departure. And each a different generation!

There are so many amazing mysteries in the natural world, and these iconic butterflies are right at the top of the list. According to MonarchWatch.org, over the summer there are three or four generations of monarch butterflies, depending on the length of the growing season. Each female lays hundreds of eggs, so the total number of monarch butterflies increases throughout the summer. Before the end of summer, there are millions of monarchs all over the U.S. and southern Canada.

We see many monarchs here on our native prairie pastures during at least a couple generational incursions: the generation that arrives first in late spring, and the final return generation heading back from Canada to Mexico.

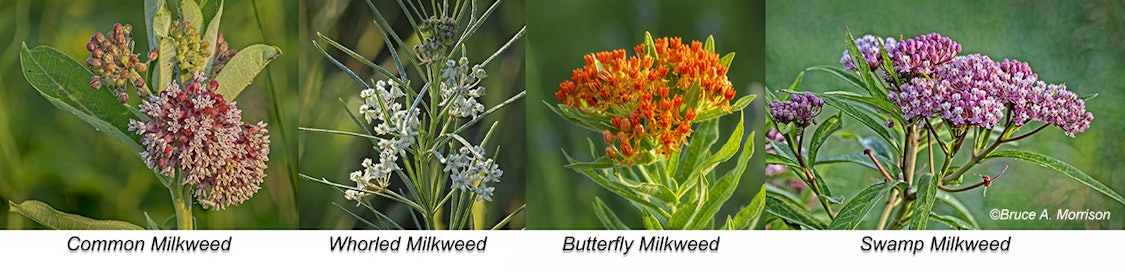

We have a very healthy population of milkweeds here—four species in most years, the most plentiful being Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) and Whorled Milkweed (Asclepias verticillata); with smaller populations of Butterfly Milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa) and Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata). So I guess we’re a pretty good staging ground for a next generation…lots of egg laying going on around here in late spring to early summer!

Curiously we seem to “always” have monarchs here…I can’t think of a week all summer where we don’t see one or two on any day. I can’t say exactly what’s going on, but each of the first generations can live (according to the USDA) up to 37 days – from egg to adult. Are we seeing generation 2 and 3 here? Good question for someone that knows more than I.

But one thing we do keep records of here are our first sightings in the spring and our first fall roosts. Home based amateur phenology, I guess you’d call it.

I also report these sightings to “Journey North” – a crowd-sourced, participatory science program of the University of Wisconsin-Madison Arboretum. It is a web-based site for “inquiry-based learning resources designed to engage students in the study of wildlife migration.” Anyone can subscribe to receive news updates and watch migration unfold in real-time on interactive maps. Anyone who subscribes can report their observations any time all year round.

I have been following Journey North and reporting our sightings there for about 17 or 18 years, starting when it was a grant-funded educational organization via the Annenberg Foundation (created in 1991). The University of Wisconsin–Madison took over the program a few years ago. Although I haven’t made a habit of it, any participants can go back through previous year records and compare their migration reports with other years. It’s all very fun for us amateur naturalists just interested in what we experience each year.

Our late summer visitors find plenty of native prairie flowers to fuel up for their journey to Mexico. Sometimes people ask about the milkweeds available at this time, but monarchs are no longer seeking milkweed at this point. They just need good sources of nectar to fuel up; the egg laying dependency on milkweed is over for the year.

It’s hard to say what they like best for migration fuel, but here they seem partial to Stiff Goldenrod (Solidago rigida), and any of the asters. New England Aster (Symphyotrichum novae-angliae) seems a huge favorite each migration. If the liatris is still blossoming, they too are like monarch magnets.

I remember well back in the early 1990s I was up near Cayler Prairie in Dickinson County, and I stopped by just for a walk around. Although I had my camera with me, it was much too windy for flower photography, and the light was getting too high for decent shots anyway. The main trail in was a big surprise – the Rough Blazing Star (Liatris aspera) was still blooming and were “covered” with monarchs…some stalks with three or four each. Oh, what a sight!

Although many other flower choices abounded – this liatris was like monarch gold! I went back the following morning and tried photographing some still on the liatris. One was so inanimate, covered in dew and spider webbing.

Monarchs on stiff goldenrod:

On New England aster:

As a quick disclaimer: don’t count out any flower in late August or early September, from garden to wild areas. Monarchs will take advantage of whatever is available. Pictured here on false boneset:

Our first monarch “Fall Roost” here on our acreage back in the early 2000s was amazing…quite a surprise for us. I guess I should have seen it coming, but was clueless as to how well set we were for this welcome overnight stay.

Our acreage is surrounded on the north and east by native pasture. The pastures are visibly covered with blossoms and attract pollinators of all kinds. The monarch migration comes in late summer. Having dropped out of southern Canada and traversed through Minnesota, there we are, like a big sign flashing “Monarch Rest Stop Ahead”!

We’re not far south of the Minnesota state line, and I often find we are usually one of the earliest (if not earliest) Iowa sites reporting Monarch “Fall” Roosts on the Journey North reporting web site.

This year our roost began on the evening of August 26, a day or two earlier than most recent past years. The numbers weren’t inspiring; I counted 63 individuals. But I was so happy to see them.

The next morning I went out and the numbers had nearly doubled to a hundred! I find it difficult to get a “close” reading on numbers during the evening roosts – so many are flitting around and not settling in. But come morning, if you get out before sunrise, the roost is set and not moving about, still chilled down a bit and maybe even a little dew covered. Still bodies are easier to count.

Since we’ve been here, our largest roost numbered near 3,000. We had typical roosts in the hundreds until around 2012 or afterward. That’s when the big crash occurred, when historic low monarch numbers became a thing.

Numbers gradually improved a fraction each year here. Looking back in Journey North, we had an early roost in 2018 on August 25 and had 20 individuals, some that roosted in the pasture on the Big Bluestems. Monarchs may not roost in trees, especially on large open areas of grasslands or prairies.

Our largest roost this year was on September 8, when we had 125. Just 45 miles away in Spirit Lake, a roost of 500 was reported the day before.

Monarch on big bluestem:

On September 5, 2019 we even had the fun event of finding a tagged monarch. The tag had a phone number on it, so I called the number and got a researcher from Florida, staying in Wisconsin. His daughter had tagged this very monarch 16 days before on August 20. It was tagged along Lake Michigan and flew due west to us! What did I say about amazing?

I blurred the tag’s phone number in this photo. Don’t think they need any phone calls because of me.

Our roosts used to be heavily concentrated on the grove’s elm branches and our big old “Homestead” pine, a red pine planted by the first owners in the late 1880s. But times change; we’ve lost all our elms due to Dutch Elm disease since then, and our red pine has been effectively killed by Dicamba drift.

I make that claim because after the bean field behind the grove was sprayed for the first time with dicamba, the next day nearly every plant and tree in the gardens and yard had cupped leaves. The red pine lost over 50 percent of its needles overnight, and it’s been a downhill decline since.

Now the preferred roosting trees “here” seem to be the ash trees. Yes, you see this coming. Emerald Ash Borer incursions are now within eyesight of us here in SE O’Brien County. Next fall will be different for us; the monarchs will either accept the soft maples or the spruces, which will make up the majority of their choices on our little spot on their route.

We have had small numbers of roosting choices on the various spruce trees in the acreage yard in the past, and some in the mulberry trees and viburnum bushes. It’s just a matter of waiting to see how things evolve, I guess. Perhaps we’ll see “pasture roosting” again?

Monarch on common milkweed:

There are a lot of unknowns ahead for all of us, and each creature on this planet is facing the same questions. Will we flourish? How will the now obvious climate change affect us? How will we adapt? Can we adapt? Will we rise to this challenge, or will the current mindset of the political arena be our collective nemesis?

There are many things to ponder. Right now I have monarchs on my mind.

1 Comment

I have two very different reactions to this post.

The first is delight at the story, the very appealing photos, and the news that monarchs are finding such a beautiful haven at Prairie Hill Farm. I used to see monarchs roosting by the dozens on a silver maple near my house every September, and I took that for granted. Now it feels as if nothing natural in Iowa can be taken for granted. I’m grateful to see such colorful evidence that monarchs are finding excellent food and shelter in part of O’Brien County. Maybe they travel safely as they continue their journey southward. And thank you, Bruce Morrison.

The second reaction is anger at reading about yet more casualties of Iowa farm chemical drift. In this case, there was significant foliar damage, which is not good for perennial plants, and a large grand tree almost 140 years old is dying.

This is not acceptable! This kind of trespass and damage is not what rural Iowans should have to expect and put up with, year after year!

Lucy Stone wrote in 1855, “…disappointment is the lot of woman. It shall be the business of my life to deepen this disappointment in every woman’s heart until she bows down to it no longer.” It is time for Iowans to stop bowing down to the ecological trespass and damage, on public and private conservation land, caused by Big Ag.

PrairieFan Fri 22 Sep 12:39 PM