Shutterstock image of an angiogram is by April stock

Rick Morain is the former publisher and owner of the Jefferson Herald, for which he writes a regular column.

I had a heart attack on the evening of February 27. All is well.

Tuesday about 7 p.m. I was sitting at the press table at the Jefferson City Council meeting, taking notes, when my chest started to hurt. I figured it was probably acid reflux, which I have from time to time, so I waited for it to go away.

It didn’t. It hung around after the meeting adjourned at 8 p.m., so when I got home I told Kathy that if it didn’t disappear by 9:30, I would go out to the emergency room at Greene County Medical Center to have it checked out.

It was still there at 9 p.m., so I moved my deadline up and we drove to the ER. They did some lab testing and an electrocardiogram, and pronounced the cause to be, sure enough, a heart attack. They gave me morphine and nitroglycerine to stop the pain (totally effective), and about midnight sent Kathy and me to Mary Greeley Medical Center in Ames in an ambulance.

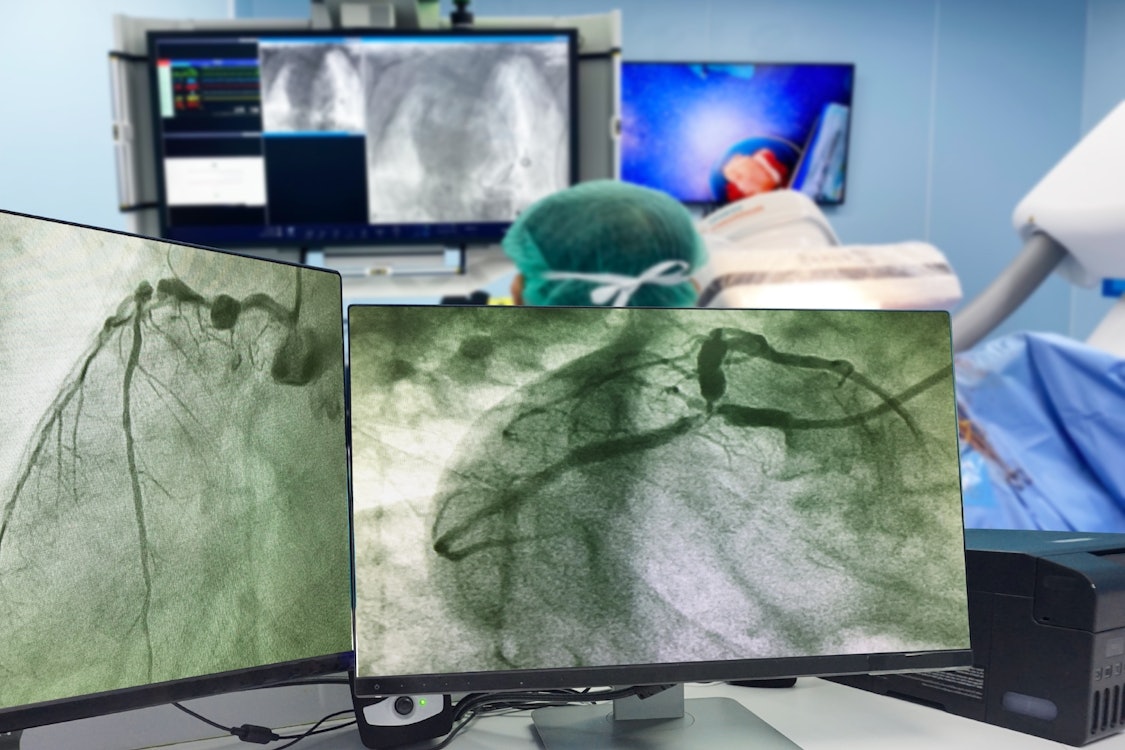

At Mary Greeley they did more lab work and an angiogram, and then sent me by ambulance to Mercy One Hospital in downtown Des Moines late Wednesday afternoon. Son David drove to Ames Wednesday afternoon and brought Kathy back to Jefferson. She stayed overnight at our house and then drove to Des Moines Thursday morning, where she and David stood watch in my room.

Another angiogram, this one at Mercy One, specified the problem: four mostly blocked coronary arteries, all on the left side of my heart.

Consultation between my Ames cardiologist and a pair of Mercy One cardiologists developed the plan. One of the Des Moines doctors was a stent specialist, and he would insert stent wires up from both sides of my groin into my heart. He would then place metal stents into the arteries to open them up.

The second Des Moines doctor, a cardiothoracic surgeon, would take over with coronary bypass procedures if the stenting proved too difficult to do.

The hospital described the situation as high risk. I didn’t know exactly what that meant. It didn’t sound like a walk in the park.

But everything turned out all right. The three-hour stenting of the four plaque-filled arteries took place Thursday morning, and went perfectly smoothly. My brother Bill, a reconstructive surgeon living in Lamoni, drove up to Des Moines to keep me company. After a stay in the recovery room to let the groin insertion wounds heal, I was wheeled back up to my sixth floor hospital room for a Thursday overnight stay and a welcome meal. We drove home mid-afternoon on Friday, and I feel great.

I learned a lot about my heart from the three-day event. For one thing, it’s 82 years old, so some plaque buildup isn’t all that unusual. In addition, a family history of heart difficulties adds to the likelihood of trouble; my dad had a heart attack about age 85, and my mom died of an aortic aneurysm at age 78. What’s more, I like all the wrong kinds of food, and that has to change. Finally, I’d rather lie on my couch than exercise, and that’s going to change too.

Specialists in matters of the heart are amazing. They know exactly what to do and/or have a Plan B in place just in case. Which means they can successfully open up, or bypass, blockages in a person’s circulatory system.

Keeping passages clear is an essential procedure in another vital organ of the human body as well. That would be the brain. And the specialists that should make those decisions? Those would be teachers.

I wouldn’t want legislators telling cardiologists what procedures they should use to keep arteries clear. And I don’t think legislators have the expertise to tell education specialists how to keep young minds open. That’s what teachers have gone to college for. They’ve learned methodologies they can use to maintain clear passages in the mind where ideas can circulate freely.

Clogging up young minds with material that’s been pre-approved on a legislative floor, and forbidding the teaching of certain established facts, erect barriers to learning and thoughtful analysis in a way similar to what plaque does to coronary arteries. Both cardiologists and teachers should be able to ply their trades free of untutored interference from lawmakers, whether well-intentioned or not.

I’m enormously grateful to the specialists who were free to open up my old heart arteries last week. I feel the same way about the teachers who did that for my young brain many decades ago.

Editor’s note from Laura Belin: On February 28, the Iowa House approved House File 2544, which would establish a new social studies curriculum with numerous mandatory topics. Rick Morain previously discussed this legislation here, and Ed Tibbetts also critiqued the bill. Prior to the vote on final passage, the House amended the bill to include a provision requiring schools to teach students about the Holocaust. Members then debated the bill for hours, with numbers lawmakers speaking for or against the concept. House File 2544 passed by 58 votes to 37, with Republicans Chad Ingels, Tom Moore, and Brent Siegrist joining every Democrat present to vote against it.

3 Comments

Glad You Are Doing Well Rick

The science of medicine is amazing for those who choose to believe in it.

Listen to your doctor and your wife. You decide in which order.

Bill Bumgarner Wed 6 Mar 6:15 PM

Happy to hear you are doing fine, Mr. Morain

In logic a good analogical argument exposes the relevant similarities between the things that are being compared. Your analogy between legislators (without the requisite expertise) telling cardiologists what procedures to employ when faced with blocked arteries and legislators (without the requisite expertise) telling education specialists what they should teach to keep young minds open was brilliant! The last thing I would want is some legislator telling me how to teach a philosophy course. Best wishes!

John Kearney

Waterloo, Iowa

John Kearney Thu 7 Mar 1:28 PM

Best wishes for a good complete recovery, Rick Morain

I know someone else who ended up at Mary Greeley after a severe heart attack and was later told that if his arrival had been delayed another half hour, he might not have made it. He is doing well twenty years later. May your outcome be similar.

PrairieFan Fri 8 Mar 11:57 AM