Dave Leshtz is the editor of The Prairie Progressive.

“Tell them you’re a realist with high ideals.”

That’s what Jesse Jackson said to me in 1987 when I asked him how to respond to my Iowa friends and acquaintances who, somewhat mockingly, called me an idealist for supporting him for president. Only unrealistic, naïve, hopelessly optimistic idealists—so the thinking went—would work for Jackson in an overwhelmingly white state like Iowa.

The sad news of Reverend Jackson’s death brought back memories of his presidential campaign of 1987-88, the most exhilarating, inspiring, and illuminating of all the campaigns I’ve worked on.

Early excitement

On April 28, 1987, I attended a meeting on polling place accessibility in Secretary of State Elaine Baxter’s office at the Iowa Capitol in Des Moines. When I returned home to Iowa City that evening, a voicemail awaited me: “Jackson is coming to Casino Night. Order more beer!”

The 1988 Iowa caucus campaign was already well underway. Senator Joe Biden was shoring up old Iowa relationships. Governor Bruce Babbitt had hired Iowa staff. Senator Paul Simon was attracting center-left supporters. Representative Dick Gephardt had already signed on to attend Johnson County’s annual Casino Night fundraiser on May 2.

The other candidates were not nearly as progressive as Jackson, none had the same charisma, and none would be nearly as much fun to work for. I knew (as did the fellow organizer who had left me the voicemail) that Jackson would inject excitement into a lackluster field and boost attendance at our local Democratic Party’s biggest fundraiser of the year. I had aligned myself with him late in the 1984 caucus race after my first choice, Alan Cranston, had dropped out. This time, I’d be with the Reverend all the way.

Within two days, more beer had been ordered and a community welcoming committee for Jackson had been formed, featuring the only rabbi in the area and Iowa City’s mayor, a Republican insurance salesman.

One day later, local attorney Jim Larew held an event at the Holiday Inn for Governor Michael Dukakis. I asked the Massachusetts governor about his recent approval of removing an adopted child from a gay couple. He said he was sorry for the two gay men, but “traditional families should have priority.”

The very next morning I got a call from Gephardt. He said he was looking forward to seeing me at Casino Night. We chatted about the St. Louis Cardinals, as we had when I picked him up at the Cedar Rapids airport for a county fundraiser a few months before. That event was a notorious one for Gephardt. He came to Iowa City as an abortion opponent but left as a staunch supporter of reproductive freedom after veteran Democratic activist Pat Gilroy explained the facts of life to him.

That night a record turnout came to see Gephardt and Jackson at the old Izaak Walton League clubhouse. Gephardt’s reception was enthusiastic. Jackson’s was tumultuous. I was asked to “stay in front of him” and make introductions as he worked the crowd, but I couldn’t keep up with him and the nearly four hundred people who wanted to meet him.

Another day had barely passed before the Gary Hart’s adultery story exploded in the news. And then another day with another candidate in town—Paul Simon. I asked him a question about AIDS. He tapped his hearing aid and gave me a lengthy answer about illegal aliens, as immigrants were at the time called by Democrats as well as Republicans.

A few days later, Johnson County Auditor Tom Slockett and I met with attorneys Jay Howe and Willard Olesen in Greenfield, a town outside of Des Moines where Jackson had established an office. There we heard that Hart was withdrawing from the race. Olesen said with a straight face, “I hope we don’t peak too early.”

“Are people really supporting Jackson in Iowa?”

Within the next two weeks we set up a meeting for Jackson at the home of Percy Harris, with hopes of raising some cash. Dr. Harris was the first Black physician in Cedar Rapids; he and his wife Lileah would prove to be key supporters and fundraisers for Jackson. Jackson was two hours late, but no one left. He understood the AIDS crisis and had no problem with gay adoptions. The little group pledged $5,000.

Jackson with supporters in autumn 1987 at the home of Dr. and Mrs. Percy Harris. Back: Clara Oleson, Dave Leshtz, Sondra Smith. Front: John Else, Loret Mast, Tom Slockett

By mid-June, John Norris had signed on as Jackson’s caucus director, and Jackson staffer Carolyn Kazdin, a labor organizer from New Jersey, had met with the committee and potential caucus supporters. Missouri Lieutenant Governor Harriet Woods came to town on Gephardt’s behalf. She seemed to be fulfilling a duty, with minimal enthusiasm.

The annual Dems New Frontier dinner in Des Moines closed out the month. Gephardt’s hospitality room was quiet and dull. Babbitt’s was deserted. Biden’s was filled with Polk County pols and high-powered lawyers (“sharks,” state senator Lowell Junkins whispered to me). Jackson’s keynote address to the entire crowd was a huge hit and raised $3,000 in the bucket pass. His son Jonathan was on hand for his first visit to Iowa.

I got a call from Phil Trounstine of the San Jose Mercury News: “Are people really supporting Jackson in Iowa?” This question typically was asked by non-Iowans who assumed that the only goal of the caucuses was to pick a winner.

Another appearance by Dukakis in Des Moines. This time I asked him about his placing of limits on foster care by gay men. He gave me the same answer about prioritizing traditional couples. After the event, two Dukakis staff members apologetically told me they disagreed with him on this issue.

By July, Jackson for President steering committee meetings were being held regularly at Tiny Tots Day Care, led by legendary Des Moines activist Evelyn “Moms” Davis.

Labor unions at this time weren’t lining up strongly behind anyone. At a caucus training sponsored by AFSCME, participants said little as staffer Ted Anderson spoke confidently of union members moving toward Dukakis. After suggesting a straw poll of preferences, Anderson was surprised by the show of hands: eight for Jackson, seven for Dukakis, zero for the rest of the field. As summer wound down, Jackson, Dukakis, and Simon increasingly looked like frontrunners in Johnson County. Biden dropped out at the end of September.

A warm reception in Greenfield

The people of Greenfield had held an extraordinary event on Super Bowl Sunday, 1987, at the Methodist Church. Jackson, accepting an invitation from farm leader Dixon Terry, came to speak and to meet the inhabitants of this Adair County town, on a cold night that no traditional politician would schedule even a phone call. The church was packed. The next day, newspaper readers across the country saw what became an iconic campaign photo: Jesse Jackson, in overalls, milking a dairy cow.

It was nearly unimaginable that a town of less than 2,000 people would embrace Jackson so warmly, turning out hundreds of people at every event, despite having only one Black resident (the adopted son of the Methodist minister). In the Iowa community that loved and respected him, Jackson opened an office that soon became his Iowa headquarters.

Nine months later, on October 10, Greenfield hosted an even more remarkable event, this time for Jackson’s official announcement.

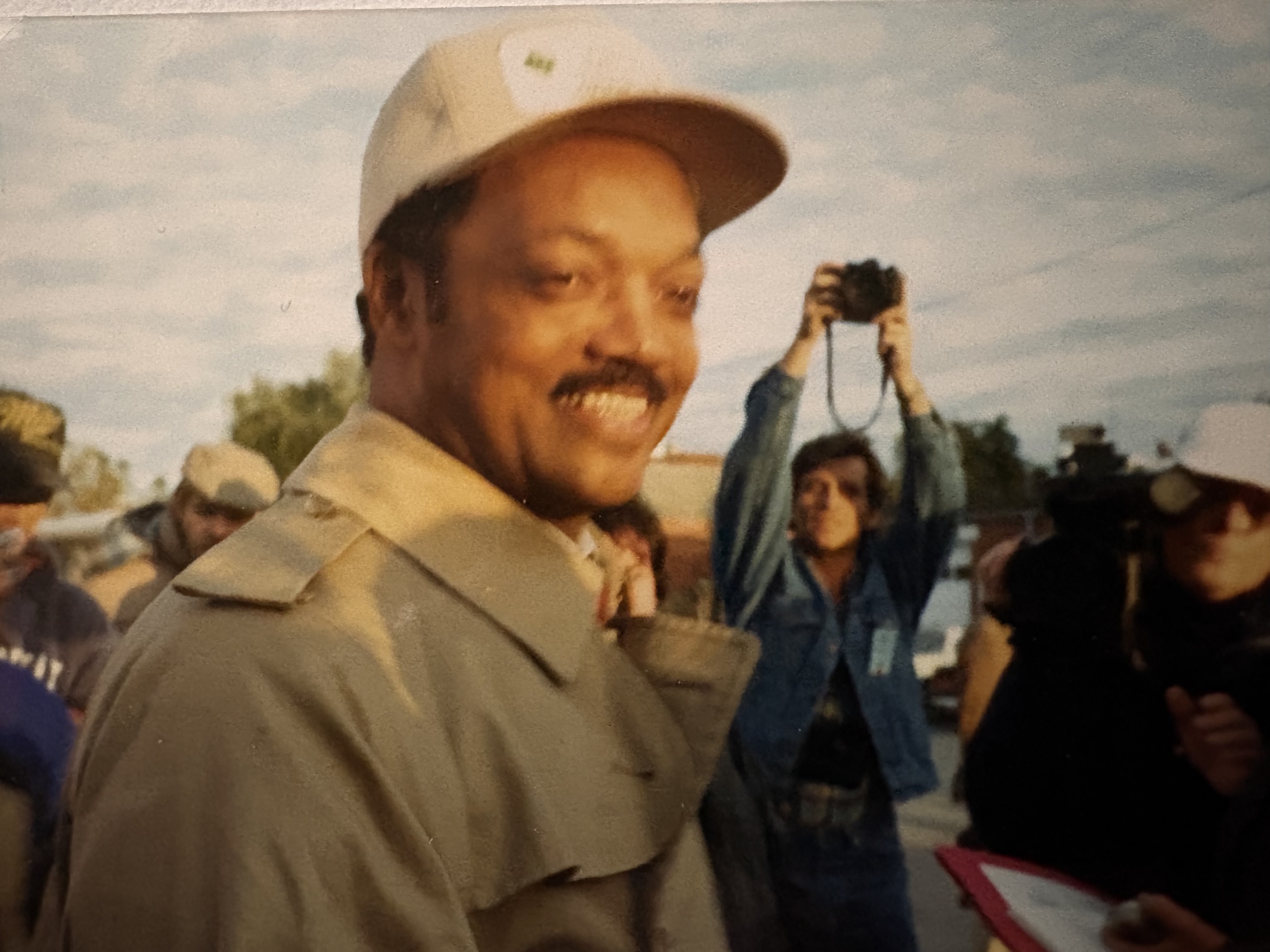

photo provided by Dave Leshtz

At Jackson’s campaign reunion in Chicago in 2023, Jackson’s caucus director John Norris recounted what that day was like:

That event in Greenfield remains the best candidate announcement I have ever seen or been a part of. The high school band marched with the Jackson ’88 parade from the town square to the 4H Fairgrounds. Jesse rode in a convertible. The Future Farmers of America stood alongside the road with a “Welcome Home Jesse” sign. At the fairgrounds we had a huge circus tent where the Boy Scouts led the Pledge of Allegiance. We had a gospel choir from Waterloo, the Teamsters Blue Grass Band, and a reggae band. The Pork Producers provided pork burgers. Can you imagine that happening today?

While Greenfield was an example of Jesse thinking outside the box, the symbolism of Greenfield and the support he was receiving across the state from farmers and rural Iowans represented a threat to the other candidates. Jesse wasn’t staying in his box. He was supposed to rally and mobilize Black voters for the general election, not take votes away from the other candidates.

Norris was right. It was the Rainbow Coalition coming alive in all its improbable glory. Halfway through the long parade, Jackson hopped out of the convertible and onto a John Deere tractor, laughing and steering it through the crowd as people cheered him on.

John Norris (left) outside the Jackson HQ in Greenfield (photo provided by Dave Leshtz)

The speaking program was one emotional speech after another, highlighted by two burly white farmers who had driven up from Chillicothe, Missouri. They spoke for only a minute or two, recounting how Jackson had come to their town to support their community during a series of bank foreclosures. Then they embraced him and burst into tears. Even seasoned political veterans shook their heads in near disbelief. None of us had never seen anything like it.

“Don’t ever leave me exposed like that”

The following month Norris and I picked up Jackson at the Cedar Rapids airport and took him to three events. He was the featured speaker at each of them – one at an Arts Center, one at the University of Iowa student union, and one at the Sheraton Hotel. Three different speeches, three standing ovations.

A week later, Jackson spoke about children and poverty in Cedar Rapids. Afterward, Iowa City artist Loret Mast gave him a bag of fried chicken wings for the road, beginning a tradition that lasted throughout the campaign. Once, when Mast was late to an event, Jackson looked around and asked, “Where’s my chicken wings?”

After an event at a hotel in Cedar Rapids, Norris and I were in a van picking up Reverend Jackson at the front entrance. As we pulled into the circle driveway, Jackson was pacing in the big lit-up doorway of the hotel. He got in the van without a word. Usually, he was exuberant after a successful event, but this time he seemed angry. We were only a few seconds late, I thought to myself – it shouldn’t be that big of a deal. Finally, Jackson turned to Norris and said, “Don’t ever leave me exposed like that.”

I looked back at the front of the hotel. Sure enough, the brightly lit double doors provided a perfect frame for an assassin’s bullet. It drove home to me the ever-present danger that Rev. Jackson lived with, and the awesome courage it took to face that ever-present danger nearly every single day.

Carlos Welty, a farmer from Boot Hill, Missouri, reminded me of Jackson’s courage at the 2023 reunion at the Rainbow PUSH Community Hall in Chicago celebrating the 35th anniversary of the 1988 presidential campaign. Welty recalled the dozens of tractors he helped line up to surround a Jackson event. Former Jackson staffers and volunteers told similar stories of other states where lines of twenty or more tractors formed barricades “to keep him from getting hurt.”

Jackson’s daughter Santita recounted some of the dangers Jackson faced, leading him to tell his children in 1983, “Go on with the work, no matter what happens to Daddy.”

“The plan is to win Iowa”

The campaign really began to heat up around Thanksgiving. Former New Mexico Governor Tony Anaya made several stops in Iowa. Jackson’s newly hired national campaign manager, Gerry Austen, introduced himself to a few of us at the Savery Hotel in Des Moines. When asked how he envisioned the campaign, Austen simply said, “The plan is to win Iowa.” At a later meeting in Des Moines, Jackson told us he hired Austen for two reasons. First, “I know the back roads and side streets. Jerry knows the main highways.” Second, ”Jerry has valid credit cards.”

Jackson, Gephardt, and Simon spoke in early December at the Iowa Citizen Action Network convention in Des Moines. A few days later, Dukakis spoke at Gloria Dei Lutheran Church in Iowa City. He waffled adroitly when questioned about the chances of a Palestine/Israel conciliation. After months of seeing and hearing Jackson in action, I was struck more than ever by the blandness and substance-free caution of the alleged frontrunner.

The weather turned cold, but Jackson’s crowds continued to grow. An event at King Memorial Chapel in Mt. Vernon featured a testy exchange between Jackson and a Jewish professor who objected to Jesse’s support for the Palestinian people. Another packed church appearance came a few days later in Tipton, a small town a half-hour east of Iowa City.

Jackson kicked off 1988 in Iowa with a speech at the Teamsters hall in Cedar Rapids. His printed materials were focused more on courage and conviction than on biography and policy, with a new attribute added: electability. His debate performance on January 16 got positive spin. The hard-core staff in Greenfield were giddily awaiting national campaign staff’s arrival as the caucuses neared.

Jackson was now being red-baited both publicly and privately. Jim Ridgeway of the Village Voice asked me to comment on a Gephardt supporter’s statement that Jackson had “pockets of strength in Johnson County among socialists,” and that other candidates were being slammed in a local socialist newsletter. When I told him the newsletter was a product of the Democratic Socialist of America, Ridgeway said, “You mean DSOC?” He laughed heartily at the idea that Michael Harrington’s Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee was being used as the S-word scare tactic.

It was now becoming clear that many McGovern and Cranston caucus-goers from 1984 were moving toward Jesse. Nevertheless, the campaign emphasized that Jackson’s support came not only from the left, but from farmers and faith-based groups as well. We started talking about the “second-choice strategy” that could prove critical at caucuses. We started talking about high-profile mainstream national figures like Democratic National Committee political director Ann Lewis “advising” Jesse. We started emphasizing electability as union members, teachers, and other reliable voters and regular caucus attenders flocked to his events.

“Go to the caucus!”

Iowa was by now the political center of the nation. Holly Near and Bill Cosby headlined fundraising events for Jackson in Iowa City. National reporters and TV crews were at every event. Coverage by caucus veterans like David Yepsen of the Des Moines Register was increasingly positive, as were reports from the campaign’s statewide phone operation.

Footage of the Missouri farmers weeping in Jackson’s arms at his announcement in Greenfield was now being featured in a national television ad. Jackson’s press secretary was honing his “electability speech.” A caucus training session at yet another church attracted seventy Jackson supporters. Jackson spoke to packed auditoriums at the two biggest high schools in Iowa City.

U.S. Representative John Conyers came to Iowa three days before the caucuses, ostensibly for a “unity party” held by Iowa Congressman Dave Nagle, but he was eager to stump for Jesse. At dinner following the Nagle event, Conyers stained his tie. Driving him to Cedar Rapids where he was going to spend the night, I handed him my own tie. “Only in Iowa would someone offer me the tie from around his neck,” he said, “and only in Iowa would I take it.”

Two days before the caucuses, the local chair of the Babbitt campaign invited County Auditor Slockett and me to discuss a classic caucus deal: if your guy is short of viability, and we can afford to give up a few people and still be viable, we’ll send them over to you; if we need a few folks for viability while you have more than you need, you do the same for us.

Slockett and I, sitting on a list that had grown to 1,500 supporters, politely declined. We knew Jackson would be able to win delegates at almost every caucus location in the county. This meeting confirmed for us that Babbitt, despite support from our county attorney and other Democratic stalwarts, was in trouble.

One day before the caucuses, we held a meeting for precinct captains, the volunteers who would hold supporters together and make deals for delegates if needed. Almost every one of the county’s fifty precincts had a designated captain. One final rally at Coe College in Cedar Rapids drew a huge, exhilarated crowd. Each time Jackson asked, “What ya gonna do,” people shouted, “Go to the caucus!” A voice cried out, “Do ‘I am somebody!’” as if requesting a rock star’s greatest hit. Jesse obliged.

Snow fell in Iowa City the next day, but a record turnout of 349 Democrats poured into the tiny Longfellow elementary school gymnasium, three blocks from my home. The final delegate count in my precinct: Jackson 4, Simon 3, Dukakis and Babbitt 2 each.

When the dust cleared that night, Johnson County results were in: Simon first, Jackson second, Dukakis third. Statewide, the official order was Gephardt edging Simon, with Dukakis third. Jackson finished fourth, with nearly 10 percent of the Iowa delegates. Babbitt, Gore, and Hart (who had reentered the race) trailed the field. (Gephardt’s razor-thin victory is disputed to this day by some veteran activists, but that’s another Iowa caucus story).

Long-term impact

What followed the Iowa caucuses is well-known: a strong showing on Super Tuesday, an astonishing Jackson victory in the Michigan caucuses, continued demands that he “repudiate” Nation of Islam Minister Louis Farrakhan, pundits’ columns shifting from “What Does Jesse Want?” to “Can He Actually Win?”

Jesse had plenty of juice going into the Democratic National Convention in the form of over 1,000 pledged delegates. Speculation grew that presidential nominee-in-waiting Michael Dukakis would have to consider Jackson for his running mate. Rumors circulated that if Jackson was not treated with the respect he had earned, he would lead his delegates out of the convention and out of the Democratic Party to start a new Rainbow Coalition party. This was seen as a credible threat, four years before Ross Perot received nearly 20 percent of the presidential vote as an independent, but Jackson stayed loyal to the Democrats.

None of these events would have happened without Iowa. Being on the ground with Jackson in a mostly white and rural state was a never-to-be-replicated experience for hundreds of political veterans as well as newcomers to the process. As Jackie Jackson observed at the Jackson campaign reunion in 2023, you can’t walk through a doorway without someone cracking it open first. Jackson cracked the door open for Barack Obama in Iowa. Twenty years later, Obama strode through the same door in the same state.

“A realist with high ideals.” Was it unrealistic to articulate genuinely democratic ideals? Was it naïve to challenge the other business-as-usual candidates with a progressive agenda? Was it hopelessly optimistic to bring together urban and rural, Black and white, farmers and workers, gay and straight, into a dynamic coalition?

Jesse – as most of us Iowa supporters called him – invigorated the Democratic Party. He registered millions of new voters. He confronted all types of bigotry at every turn. He educated audiences of all kinds (every speech I heard him give was a lesson in American history). And every speech ended with a call to action and a charge to never give up.

Now, in 2026, open doors have been slammed shut. Slammed shut on immigrants, legal as well as undocumented. Slammed shut on universities striving to serve students from all walks of life. Slammed shut on public libraries, historical societies, public radio, scientific research. Slammed shut on transgender people. Slammed shut on SNAP recipients and, most brutally of all, on uninsured people depending on Medicaid to pay for their health care.

What, and who, will it take to open those doors again? It’s too soon to tell, but New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani has a lot in common with Jackson in his prime. Like Jackson, he organizes the people that establishment Democrats have forgotten. Like Jackson, he emphasizes the issues they have abandoned. Like Jackson, he envisions a world they are too timid to fight for. His energy approaches that of Jackson, who in his prime was the hardest-working politician in America. Above all, Mamdani understands the power of economic and social justice.

But there is only one Jesse Louis Jackson. It’s his life that inspires so many of us to “go on with the work.”

Editor’s note: Dave Leshtz gave Bleeding Heartland permission to publish a few more of his photos. Jesse Jackson speaking with his former Iowa state director John Norris at an Iowa Farmers Union event in the early 1990s:

Campaigning in Des Moines in 1988:

Two photos of Jackson with longtime Iowa legislator Dick Myers in Iowa City:

1 Comment

AOC is the obvious air to Jesse

https://newrepublic.com/article/206656/jesse-jackson-dead-economic-argument-30-years-later

dirkiniowacity Wed 18 Feb 9:58 PM