Leslie Carpenter: Eliminating inpatient psychiatric beds has dire consequences for people with serious brain disorders. -promoted by Laura Belin

Mercy Iowa City recently announced that it will be closing its inpatient psychiatric unit, due to “the financial impact of COVID-19.” Hospital officials confirmed that the unit (recently staffed for ten inpatient beds) will close by the end of the calendar year, “in favor of expanding our outpatient service where there is greater community need.”

However, outpatient care is no substitute for patients who need inpatient care. In fact, there’s no state in our country that needs to expand inpatient care more than Iowa.

Michaela Ramm reported for the Cedar Rapids Gazette on September 25 that some patients affected by Mercy Iowa City’s decision “may be taken in by the mental health regions, which was expanded by state officials in an effort to direct this care for adults and children from state institutions to community-based service providers.”

To clarify, a mental health region (Iowa MHDS Region) is an administrative entity responsible for coordination, oversight, and in some cases funding of actual mental health services. But MHDS regions do not operate inpatient psychiatric units. So they cannot provide inpatient care for the patients who will be displaced by this closure.

Hillary Ojeda reported for the Iowa City Press Citizen on October 5,

And while Johnson County residents may be losing the psychiatric unit at Mercy Iowa City, a new mental health facility is scheduled to open in early 2021.

The GuideLink Center, a collaboration between Johnson County officials and other local service providers, will offer short-term mental health and substance use disorder treatment.

It is important to note that GuideLink is meant to be used for crisis intervention. It will not provide inpatient psychiatric care for the patients who will no longer be able to be hospitalized at Mercy Iowa City.

As a physical therapist, I understand that hospitals are businesses. As an advocate for people with serious brain disorders, I also understand reimbursement for mental health care services (in all settings) is less than optimal. This is why I’m advocating for an increase in reimbursement rates and the lifting of lifetime Medicaid and Medicare caps for people with brain disorders.

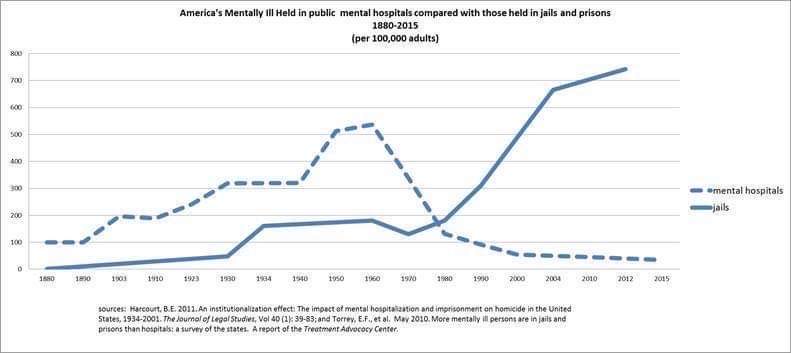

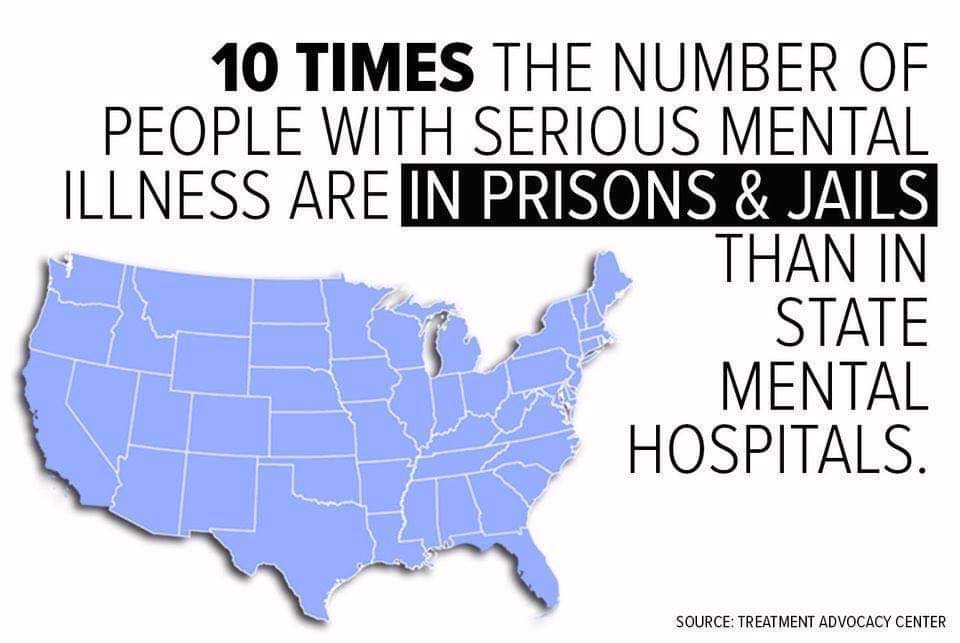

In addition, I’m advocating for ending the Institute of Mental Diseases (IMD) Exclusion, a federal policy from 1965 that legally discriminates against people with brain disorders by preventing the use of federal matching Medicaid dollars from being used for any facility with more than 16 beds dedicated to the care of patients with “mental diseases.” That includes people with mental illnesses and with intellectual deficits. The policy has led to massive over de-institutionalization of people with brain disorders. It has not ended the atrocities it was meant to avoid; it just relocated where they happen.

Eliminating inpatient psychiatric beds has dire consequences for people with brain disorders. Some will say, well, but its only ten or twelve beds. The problem is that Iowa ranks 51st in the country for the number of state-operated, long-term psychiatric beds, with only 64 for adults and 32 for children.

When you add the number of inpatient psychiatric beds operated by private hospitals in Iowa, the total is between 750 and 800 beds for 3.1 million Iowans. In addition, inpatient beds are subdivided for use by children, adult, and geriatric patients, further limiting access for Iowans who need a specific type of care.

Another complicating factor: because there are so few residential care facility beds for those who truly need 24/7 supervised care, many beds at acute care hospitals (particularly the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics) are being used by patients who could move to a residential care facility, but are waiting for those beds to become available. As a result, patients presenting to hospital emergency rooms needing inpatient psychiatric care will have longer waits for those beds, or will be transported away from their families to receive inpatient care.

It’s a sad reality.

Hospitals and outpatient mental health providers are allowed to say, in effect, “we’re choosing to not provide care” to the very patients who most need treatment: those with the most serious brain disorders like schizophrenia. In the health care sector, that is known as cherry-picking – actively choosing to treat only those who are less sick and less likely to need hospital care to manage their illnesses.

Where will these people needing inpatient psychiatric care go? Unfortunately, many will end up going to the only places that cannot say no: public hospital emergency departments, our streets, our jails and prisons (for crimes they may commit while untreated), and our graveyards.

Our police, who cannot say no, end up being tasked with the care of people in crisis. While our local law enforcement agencies utilize their Crisis Intervention Training, it should not be their responsibility to take care of people who mental health agencies, professionals, and hospitals refuse to treat.

These types of decisions have real, potentially tragic consequences for our most vulnerable citizens.

I took the opportunity to read Mercy Iowa City’s published mission statement.

MercyOne serves with fidelity to the Gospel as a compassionate, healing ministry of Jesus Christ to transform the health of our communities.

The organization’s stated values include,

Commitment to the Poor

We stand with and serve those who are poor, especially the most vulnerable.

I’m deeply saddened that this hospital is choosing to stop providing inpatient psychiatric care for the very people they say they are seeking to serve – the most vulnerable members of our community.

I’m dismayed that our state and federal governments don’t act to fix the financial situation that led this hospital to make a decision that seems to be counter to their most basic mission and values.

If you care about people with brain disorders and want to help fix our broken treatment system, I invite you to join in our advocacy.

Write a letter to the editor. Contact Governor Kim Reynolds to suggest she re-open long-term state-operated psychiatric beds, and increase reimbursement rates in Iowa’s contracts with the Medicaid MCOs (Managed Care Organizations) for mental health professionals and direct care staff. Contact your state and federal legislators. Contact the administrators of Mercy Iowa City to express your concerns about this specific closure.

I’m left wondering: What would Jesus do?

Leslie Carpenter is an advocate for people with serious brain disorders, the president-elect of NAMI Johnson County, and a founding member of Iowa Mental Health Advocacy. The views expressed here are her personal views, not those of NAMI Johnson County. Leslie can be reached at lcarpenter@iamentalhealth.com.