Governor Kim Reynolds authorized using state resources to conduct COVID-19 tests at a workplace that had only one confirmed case after the company’s owners reached out to her last May.

Iowa National Guard and Iowa Department of Public Health (IDPH) personnel facilitated coronavirus testing at GMT Corporation, a machine parts manufacturer in Waverly, on May 22, 2020. Fewer than a dozen Iowa businesses received such visits during the two months the state’s “strike team” program was active, when coronavirus testing kits were not widely available.

Summit Ag Investors, the asset management arm of Bruce Rastetter’s Summit Agricultural Group, owns a majority interest in GMT. Emails Bleeding Heartland obtained through a public records request indicated, and GMT’s top executive confirmed, that someone from Summit Ag “contacted the governor directly” after GMT staff learned they “would most likely be denied” testing assistance from the state.

Neither Summit Ag executives nor staff in the governor’s office responded to Bleeding Heartland’s inquiries.

“OUR OWNERS CONTACTED THE GOVERNOR DIRECTLY”

Bremer County Health Department administrator Lindley Sharp wrote to GMT’s Jamie Kramer on the morning of May 18,

I just received a call from the State that GMT put in a request for mass testing. Both myself and the Bremer County Emergency Manager would like to know why neither of our organizations were contacted or given a heads up regarding this request? Also, have you had 3 or more employees test positive?

In some contexts, state public health officials consider three or more confirmed COVID-19 cases to be an outbreak.

Kramer replied that she had called the previous Monday (May 11) after learning a GMT employee had tested positive. Sharp was not available, so Kramer left a voicemail. When someone else with Bremer County Health returned the call, Kramer wrote,

I requested testing and was told that we would most likely be denied with only one case. Our owners contacted the governor directly and she authorized the testing for us.

Sharp wrote back asking to speak with the owners.

The State was not aware that GMT went over local government to put in this request.

The bigger matter with this request is that the Bremer County Emergency Manager put in a request over 3 weeks ago that our county get all long term care residents and essential healthcare workers in our County tested and we’ve yet to get a response back on that, but a multi-million dollar corporation like GMT puts in a request and gets approved in a day when said organization has only had one positive case.

Sharp was understandably annoyed. Reynolds had announced on April 16 that the IDPH was creating “strike teams” to conduct COVID-19 testing at long-term care facilities or large businesses “where outbreaks are occurring or anticipated.” Bremer County was among the first group of Iowa counties to document a nursing home outbreak; by mid-April, Bartels Lutheran Retirement in Waverly had identified at least nineteen cases. The state confirmed the first COVID-19 death in the county on April 23. Four Bremer residents had died by mid-May.

Moreover, the county was in the northeast Iowa region where Reynolds imposed stricter limits on social gatherings during the second half of April, due to increased coronavirus spread.

Bremer County’s Emergency Manager Kip Ladage recalled in an October telephone interview that he had requested COVID-19 testing for area long-term care employees through the state’s normal process, using software called WebEOC. That software sends requests to the state’s Emergency Operations Center, which forwards the inquiry to the appropriate department (the IDPH for pandemic-related matters). Ladage didn’t attempt to contact anyone at the governor’s office or state public health directly. “I have to follow the channels.”

GMT was not similarly constrained.

“THEY SAID THAT THEY WOULD OF COURSE COME HELP US OUT”

During a telephone interview in December, GMT’s president and CEO Steve Snedegar confirmed that “someone at Summit” contacted the governor. He wasn’t sure who spoke to Reynolds. Neither the governor’s communications staff nor anyone from Summit Ag responded to messages seeking to clarify whether Rastetter (the CEO) or another Summit Ag executive reached out to Reynolds, when that conversation occurred, and whether they communicated over the phone or by some other means.

GMT contacted the Bremer County Health Department first, Snedegar explained. “We were told that they couldn’t do anything for us.” Since the company is among the area’s larger employers, “I escalated.” GMT had been following COVID-19 safety protocols from the beginning, Snedegar said, but knowing how the virus had spread in some of Iowa’s food processing plants, “We didn’t want to have that sort of problem here.”

He noted that at that time, people often waited weeks to access COVID-19 testing. GMT has three factories in Waverly and a total workforce of just over 230 employees, working three shifts. Snedegar didn’t want to risk an outbreak that could spread into communities “all up and down Cedar Valley.”

Kramer told local reporter Anelia Dimitrova of the Northeast Iowa newspaper group that the confirmed case had been out sick before testing positive, “so the risk of exposure was minimal.” Nevertheless, GMT leaders sought to test all employees as a precaution.

Someone from GMT reached out to the IDPH, Snedegar told me. They were either unresponsive or said they couldn’t help.

So we took it to the governor’s office. I knew that there were some people within Summit that might have some connections to the governor’s office, and so that’s what we did.

And they contacted the governor, and next thing you know I’m getting a call from a guy on her team, and they said that they would come, they would of course come help us out. You know, they had to get approval for it, but they said that they would of course come help us out.

Snedegar couldn’t remember who called from the governor’s office and later said he couldn’t locate that name in his email records. He was sure it was a man. Policy advisor Jake Swanson and communications director Pat Garrett were among the governor’s staff copied on a planning email sent out a few days before the GMT testing. Reynolds’ chief operating officer Paul Trombino III was involved in many aspects of the COVID-19 response as well.

Dimitrova’s article about the strike team visit noted, “The Iowa National Guard delivered the tests, helped set up the premises, ensured the lined employees stayed 6 feet apart while waiting to be tested and delivered the tests to the University of Iowa labs.”

The National Guard “did a terrific job,” Snedegar told me. “I was super impressed with how organized they were.” Every test taken at GMT that day came back negative.

FEW COMPANIES RECEIVED IOWA NATIONAL GUARD HELP WITH TESTING

Beginning last June, I have periodically asked the IDPH for details on the strike team program. How many sites had Iowa National Guard assistance with COVID-19 surveillance testing? What criteria were used to select counties for deployment of a team to test employees at nursing homes, food processing plants, or other large manufacturers? Communications staff never responded to those messages over the summer.

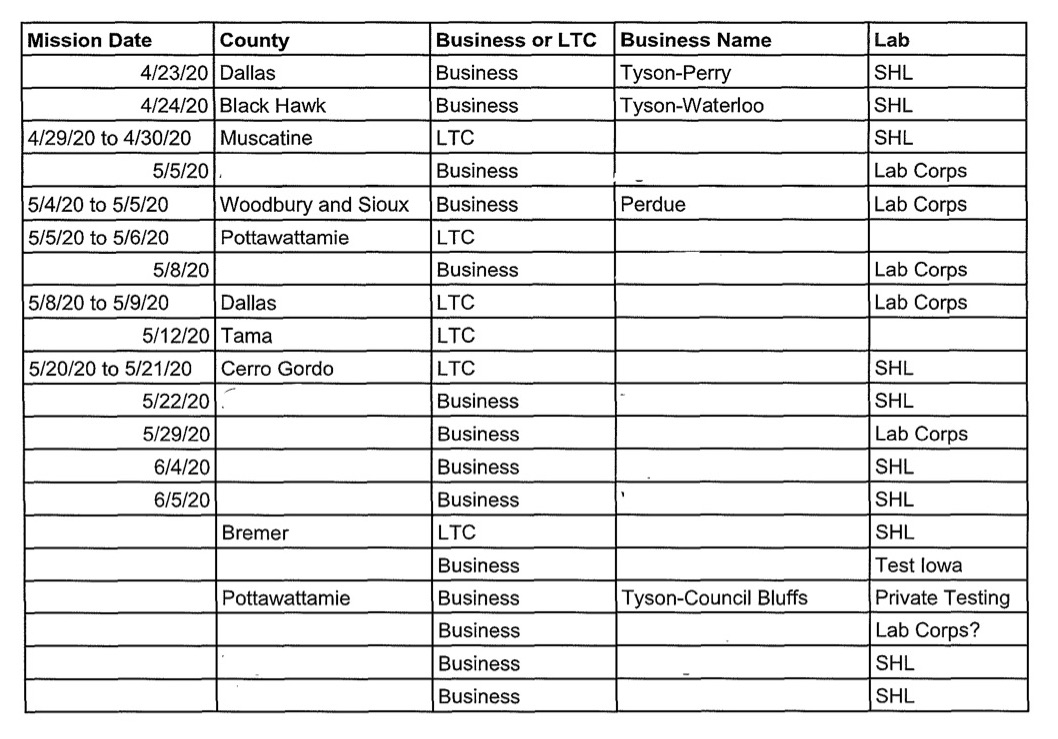

IDPH has yet to provide most of the records I requested in December related to the program, or even an estimate for the cost to retrieve and review some of those documents. However, on January 12 the agency’s top communications staffer Sarah Ekstrand shared one page, purporting to list all strike team visits.

A few corporate names are listed, presumably because the state-assisted surveillance testing at Tyson or Perdue meatpacking plants already received widespread media coverage.

The agency withheld some company names, citing a provision in Iowa Code that says information about a disease “may be reported in public health records in a manner which prevents the identification of any person or business named in the report.” As discussed above, the May 22 testing occurred at GMT Corporation. The Waukon Standard reported that a strike team visited the AgriStar meat and poultry processing plant in Postville (Allamakee County) on May 5.

I wasn’t able to determine where strike teams conducted COVID-19 testing on May 8, May 29, June 4, or June 5. (Please contact me if you have further information.)

Although this document shows fourteen strike team visits to businesses, only nine have a date attached. Ekstrand clarified on January 20 that the five undated rows should not have appeared on the chart. “There were no state staff or assets deployed to those sites. IDPH was not involved in the testing at those sites so we don’t have date documentation.”

How is it possible that the state’s public health agency doesn’t have a record of when mass testing occurred at any large Iowa workplace? Ekstrand replied, “The sites with no dates were locations that indicated they needed testing, then, secured their own testing either through local public health or a private testing group.”

That is plausible. I separately confirmed that the wind blade manufacturer TPI Composites contacted the governor’s office in April after identifying “a significant number of cases” at their Newton facility. The state provided COVID-19 test kits only, TPI’s general counsel said via email in December. MercyOne nursing staff administered the tests, which the State Hygienic Laboratory processed.

Assuming Ekstrand has provided accurate information, strike teams involving the Iowa National Guard were deployed to nine workplaces from late April through early June. UPDATE: The Iowa Department of Public Health disclosed in April 2021 that strike teams were sent to at least five other businesses during that date range.

The contrast Bremer County’s health administrator highlighted eight months ago remains striking: while her county’s emergency manager was left hanging for weeks, GMT got approved quickly after learning of a single COVID-19 case in its workforce.

ONLY SIX COUNTIES RECEIVED STRIKE TEAM TESTING FOR NURSING HOMES

Reynolds acknowledged on May 5 that “many counties” had reached out seeking a strike team. She said state officials “remain focused on targeting communities where [virus] activity is increasing or already high,” a message she repeated later that month.

But not all counties with rising case counts were able to obtain National Guard assistance for testing long-term care workers last spring.

Public health officials in Dubuque County, an early hot spot and the site of Iowa’s first confirmed coronavirus death, requested a strike team on April 29 to test residents and employees at a nursing home with an active outbreak. County health executive director Patrice Lambert also asked for a Test Iowa site to address rising cases elsewhere in the Dubuque area. State officials told Lambert those resources weren’t available but ended up sending 1,000 test kits to the county, on the condition that Dubuque government and health care organizations arranged for testing locations and personnel.

Similarly, local officials in Buena Vista County “made our own strike team” to test nursing home residents and staff, county public health coordinator Pam Bogue told the Storm Lake Pilot-Tribune in mid-May. Several meatpacking plants are located in Storm Lake, and outbreaks there fueled Iowa’s worst explosion of coronavirus cases. Even now, Buena Vista County has a far higher rate of total COVID-19 cases per capita than any other Iowa county: 19.9 percent of residents have tested positive. Only ten counties in the entire U.S. have a higher share of the population confirmed to have been infected with the virus over the course of the pandemic.

Going back to the document IDPH provided, we can see that strike teams visited six counties to test long-term care facility workers.

Although this page indicates a strike team was in Tama County on May 12, contemporaneous news accounts show the National Guard helped set up testing for long-term care employees in Tama on April 22. I’m seeking to clarify whether IDPH brought the team back to that county a second time, or whether the chart lists the wrong date. UPDATE: Ekstrand confirmed on January 25 that the strike team testing occurred in Tama County on April 22 and April 23, not in May.

Media reports verify the strike team visits to Muscatine, Pottawattamie, Dallas, and Cerro Gordo counties (the last was available to some Worth County residents as well).

No date appears next to Bremer County, but Ekstrand said the testing happened there on May 28 and May 29, which is consistent with reporting in the Waterloo/Cedar Falls Courier. That testing was only for long-term care staff in Bremer. It wasn’t available to employees at a nursing home in Shell Rock, the Butler County town just down the road from Waverly.

Perhaps IDPH records will eventually shed light on why the state deployed National Guard personnel to test long-term care workers in some counties but not others. Notably, Bremer County’s strike team was scheduled the week after Sharp had complained GMT “went over local government” to put in its request.

SUMMIT AG’S TEAM GAVE GENEROUSLY TO REYNOLDS

Few Iowa GOP donors are more influential than Bruce Rastetter. He was among the largest contributors to the 2010 and 2014 campaigns of Terry Branstad, the current governor’s mentor. Not only did Rastetter give lots of cash–at least $140,000 to Branstad’s comeback bid and $70,000 to his final re-election effort–he regularly provided flights on a private plane as in-kind donations (see here and here). Rastetter has given $111,500 in cash and four free flights to Reynolds’ campaign committee since 2015. The most recent donation was a $25,000 check dated December 30, 2020.

The Summit Ag CEO’s brother Brent Rastetter gave the Reynolds campaign $10,000 on December 30. A state database shows his only previous donation to her campaign was for $500 in 2017. Brent Rastetter has long donated to a range of Iowa GOP candidates but wrote only one other five-figure political check in the past decade ($10,000 to Branstad’s campaign in 2013).

Several senior figures in Summit Agricultural Group also donated to the Reynolds campaign in late 2020:

Senior adviser Bill Laverack gave $15,000 on December 31. That was the Florida resident’s only recorded donation to any Iowa candidate or political committee in the past two decades.

Summit Agricultural Group president Eric Peterson gave $5,000 on December 29. It was his first recorded contribution to the Reynolds campaign and the first time he had written a check larger than $500 to any Iowa campaign.

Summit Ag Investors president Justin Kirchhoff gave $2,500 on December 30. Like Peterson, he had not donated to Reynolds before, nor had he made any political contribution exceeding $500 in Iowa.

Larry and Jill Graening, who founded GMT in 1973 and sold a majority interest to Summit Ag in 2019, are not large political donors. Over the past fifteen years, they have written only ten checks to Iowa committees, mostly to the Iowa Industry PAC or to Bill Dix, who represented a nearby area in the state Senate until March 2018. However, the Graenings did write a $150 check to the Reynolds campaign on December 17, 2020. State records show it was their first contribution to any Iowa political committee in five years.

Neither Snedegar nor anyone else on GMT’s management team has donated to the Reynolds campaign or made any contributions to Iowa political committees, according to state records.

I will update this post as needed with additional information on Iowa’s strike team program.

UPDATE: State Auditor Rob Sand announced on January 26 that his office will investigate the use strike teams. Referring to the emails between Bremer County’s public health administrator and a GMT employee, Sand said, “We don’t know what a review will uncover, but these emails are plain enough that a review is certainly necessary to promote transparency and encourage the most appropriate and effective pandemic response possible.”

Reynolds appears likely to contend that she approved testing for GMT not because of any relationship with Rastetter, but with a view to protecting manufacturing supply chains. The governor’s office provided the following statement to some reporters on January 26: “At a time when COVID-19 testing was scarce, our teams worked around the clock to get testing to long-term care facilities, food processing facilities, and companies critical to the supply chain.”

Top image: Governor Kim Reynolds speaks at a May 13, 2020 news conference, while Iowa Department of Public Health Deputy Director Sarah Reisetter looks on. Photo by Kelsey Kremer/Des Moines Register (pool). Email records show Reynolds approved COVID-19 testing for the GMT Corporation sometime between May 11 and May 18.

No Comments