Iowa State University economist Dave Swenson compares Iowa’s per capita COVID-19 case rates and death rates to the numbers for neighboring states, the national average, and the best-performing state (Vermont). -promoted by Laura Belin

It is good that Iowans are getting their COVID-19 vaccinations apace. Iowa now ranks in the top half of states for having administered one dose, as gauged by percentage of population, and in the top third of the states for having administered a second.

No matter how well the state performs on vaccinations in the next few months, though, it will never excuse Iowa’s abysmal record over the past year in caring for its residents.

Iowa ranks seventh worst among the states in its incidence of coronavirus cases per capita, and 17th worst in its death rate. In short, Iowa’s political leadership, its perceived commercial imperatives, and its citizens unarguably came up short when compared with the rest of the U.S.

It all could have been more dire, some wag will say. Had Iowa the same case rate as nation-worst North Dakota, there would have been 22 percent more sick Iowans. Had Iowa the same death rate as New Jersey, where the pandemic emerged early and disastrously, it would have lost 51 percent more of its residents than it did.

But it all could have been so much better.

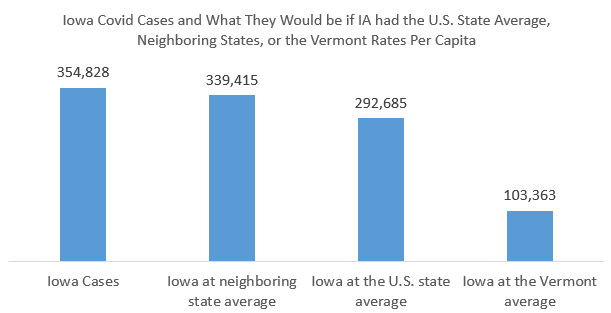

Comparisons with other states involve taking their standardized case rates per 100,000 residents and applying them to Iowa to see how much it might have fared if it had done at least as well as its bordering neighbors, the national average rate for all states, and Vermont, the hands-down gold standard in pandemic management in the U.S.

Why Vermont? Why not? Why wasn’t standing out among the best in the nation in terms of COVID-19 management Iowa’s goal from the outset? Why?

On a per 100,000 residents basis, Iowa had about 4.3 percent more cases than the average of its neighboring states, a group average worsened considerably by the very high rate found in South Dakota. It had 21.2 percent more cases than if it had the 50 state average, and a whopping 243.3 percent more cases than Vermont.

But it is the death statistic that gives one pause. On a per 100,00 residents basis, Iowa had 20.5 percent more deaths than its immediate neighbors averaged, 17.8 percent more than the national average, and 400 percent more deaths than Vermont did.

If Iowa could have done as well as Vermont, there would have been 4,700 fewer Iowa deaths. Let that sink in.

I advance three reasons for Iowa’s comparatively poor outcomes. First, leadership at the state executive and legislative levels were preoccupied with minimizing disruptions to both the political and commercial status quo more so than minimizing pandemic outcomes. State policy clearly prioritized doing the least necessary to manage the actual pandemic in terms of the scope of state responses, testing, targeted initiatives, federal guidance, acceptance and utilization of in-state expertise, and perhaps most of all its communication of all relevant information pertinent to maintaining an informed citizenry.

And it must never be forgotten that governor Kim Reynolds spent the month of October 2020 mostly engaging in partisan political activities while COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations were skyrocketing. Politics were her chief focus. No claim to the contrary is credible.

Second, the prerogatives of Iowa commerce hold great sway. Notoriously, rampant outbreaks within Iowa’s meatpacking and processing facilities were minimized, obscured, denied, and then when they could be no longer ignored, glossed over as just one more cost of doing business. Those operations’ collective responses were scandalous, and the state of Iowa did little to intervene early on. Iowa’s commercial restrictions hesitancy extended well-beyond slaughterhouses, for sure, but those instances stand out: their victims were disproportionately foreign born, minority, already marginalized, and clearly ill-served by the state even though their collective pandemic vulnerabilities were well documented beforehand.

Last, too many Iowans failed their neighbors. Some places did well, many others did poorly. Worst of all, and this applies as well to both state policy makers and to commerce, Iowa had more than ample opportunity to see exactly how this disease progressed and what the consequences were of unchecked spread. Many Iowans and communities were indifferent to, minimized, or misrepresented the seriousness of the pandemic.

Why couldn’t Iowa have been more like Vermont?

The pandemic threatened Vermont’s borders more severely and much sooner than was the case in Iowa or the Midwest. Their governor is a Republican, but their statehouse is overwhelmingly represented by Democrats. Policy and COVID-19 protective actions were bipartisan, and the result of that shared urgency was outstanding care and protection of its residents. They took the pandemic as it was, as they were told, not as they wanted it to be.

Iowa leaders brag about the state’s low unemployment rate, currently at 3.6 percent, as justification for its self-flattering balanced COVID-19 response. Vermont’s unemployment rate is 3.1 percent. Try again, Iowa.

There are other states down there with Vermont like Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Maine, New Hampshire, and Colorado. Those states are bigger and smaller than Iowa, and they run the spectrum from solid blue to solid red, yet they all massively outperformed Iowa.

That is their merit, and Iowa’s shame.

Top image: Spc. Ben Falkers with the 294th Medical Company Area Support operates a lane at a Test Iowa site at Kirkwood Community College in Cedar Rapids, Iowa on May 7, 2020. U.S. Army National Guard photo by Cpl. Samantha Hircock, in the public domain and available via Wikimedia Commons.

1 Comment

Thank you, Dave Swenson!

Iowa is fortunate to have you here, and I’ve talked with other Iowans who feel the same way.

Forty years ago, I would have believed that the facts and reasoning in the essay above would make a big difference in the next Iowa election, because I believed Iowans really cared about facts. I miss that belief.

PrairieFan Thu 15 Apr 1:32 PM