Gun violence doesn’t originate at the schoolhouse door, and it won’t be solved there. Our policy making and political rhetoric urgently need to reflect this reality.

Nick Covington is an Iowa parent who taught high school social studies for ten years. He is also the co-founder of the Human Restoration Project, an Iowa educational non-profit promoting systems-based thinking and grassroots organizing in education.

Around 7:45 on the morning of January 4, I was headed home after dropping my daughter off at her elementary school when I thought nothing of pulling over for an Iowa Highway Patrol car, lights and sirens blaring, headed west. Hours later, as reports came in, I saw state troopers were among the first on the scene at Perry High School, at the edge of a small Iowa town about 30 minutes due west of my own. A 17-year old student had inaugurated another year of gun violence in American schools, killing a 6th grader and injuring five other students and two staff before taking his own life.

Those dopplered sirens were an unsettling connection between my ordinary morning drop-off routine and the nightmare that had visited families of a nearby community; another sign of the persistent and unique exposure to gun violence that only the United States allows.

Even as the scene in Perry was being investigated, predictable responses and vicious rumors flooded social media. Among the most common was a renewed call for “hardening” schools as potential sites of gun violence, which by various accounts can mean controlling access to a single entry point, installing bulletproof glass and metal detectors, hiring armed guards, arming teachers, or all of the above.

The last bout of “school hardening” discourse took the form of “door control” following the murder of nineteen students and two teachers at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas. This year, GOP presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy has criss-crossed Iowa repeatedly calling to shut down the federal Department of Education and use the money to fund “three armed security guards in all schools.”

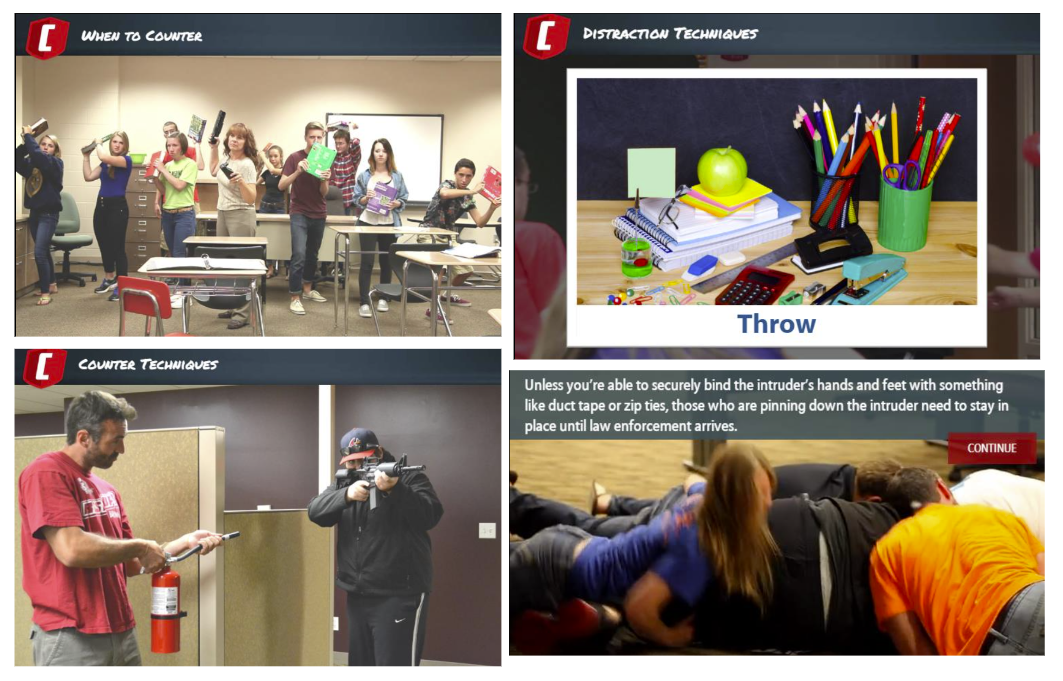

But the security-industrial complex of school hardening goes back a quarter-century to Columbine High School. As any student, parent, and school worker can attest, in the wake of the Columbine mass shooting in 1999, schools made significant changes to building accessibility and security protocols. A legion of private vendors, contractors, and consultants also emerged to sell districts, school leaders, and parents on any number of products and services: security cameras, School Resource Officers and private security guards, lockdown drills, lockdown shades, classroom door locks and emergency supplies, bulletproof backpack inserts, tourniquet and bleed control kits, “ALICE training,” and so on.

Screenshots by Nick Covington taken during a staff ALICE training in Ankeny schools in 2018

All of those measures were intended to reduce the likelihood and extent of gun violence at school; to prevent another Columbine from ever happening.

Yet there have been 394 school shootings since Columbine, impacting more than 360,000 students who have experienced gun violence at school. It defies reality to argue that schools haven’t undergone significant hardening since Columbine, and it misses the point that schools have become safer, more secure places at the same time school shootings have become more numerous and deadly.

Gun violence doesn’t originate at the schoolhouse door, and it won’t be solved there. Our policy making and political rhetoric urgently need to reflect that reality. Instead, elected officials have made communities less safe by under-funding social spending and school programming that contributes to community health and safety while expanding access and availability of firearms.

In a year when Iowa reported a budget surplus of $1.83 billion, Governor Kim Reynolds rejected participation in a federal program that would otherwise provide summer meal support in 2024 for Iowa kids from low-income families, calling the meager $2.2 million investment “not sustainable.”

Reynolds also announced a troubling “comprehensive review” of Iowa’s Area Education Agencies, which provide school psychologists, social workers, content specialists, and services for students with disabilities. The Republican-led legislature previously cut $30 million from the state budget for AEAs. Iowa schools have also had to do more with less, as multiple years of inadequate per pupil spending increases have failed to keep up with inflation. (Not to mention harmful education legislation targeted at so-called “divisive concepts” that have caused LGBTQ+ youth and their families to flee the state.)

So what does Gov. Reynolds plan to do with the nearly $2 billion surplus, if not reinvest it in Iowa families and communities that need it most? Reduce tax rates for the highest earners and corporations and expand state funding for private education, of course.

Just as it is uncontroversial to say smoking is directly linked to chronic illness and early death, the most consistent and uncontroversial conclusion from the study of gun violence as a public health threat is that more guns lead to more gun violence. More guns lead to more homicide, more homicides of police, more violence and intimidation, and more suicide—all disproportionately affecting the young, women, non-white, and low-income communities.

In 2021, guns surpassed motor-vehicle crashes, cancer, suffocation, and drug overdoses to become the leading cause of death for children in the U.S. Even before the 2023 legislative session, Iowa had among the weakest gun laws in the country. In spite of this, the Iowa House approved bills last year allowing guns to be kept in locked vehicles on school and college campuses, and allowing Iowans access to guns who were previously barred from carrying firearms.

According to the gun violence prevention group Everytown For Gun Safety, despite relatively low levels of gun violence overall, gun deaths per 100,000 Iowans have grown since 2011 at a much faster rate compared to the rest of the United States.

How can our leaders consider programs that support the health of Iowa kids, families, and communities “not sustainable,” while not applying the same label to their failed laissez-faire attitude toward gun policy? Why should our state’s response to the tragedy in Perry be to put more guns on school campuses and more public money into the pockets of private security vendors, instead of making a robust investment in public schools more broadly?

Why is the only vision our elected officials offer for Iowa’s future down the barrel of a gun?

Top image of a gun with school supplies in a classroom is by Africa Studio, available via Shutterstock.

3 Comments

Well Said

You’d think, by now, pro-gun policy elected officials would be embarrassed to offer their thoughts and prayers following yet another school shooting.

Their solution is more guns.

Bill Bumgarner Sat 6 Jan 8:24 PM

Ooops

Hit send too soon.

It was a good day when insurers walked away when some Iowa school boards thought it was sound policy to arm school employees.

The data is clear. More guns lead to more homicides and more suicides. The concept of a “good guy with a gun” is largely a myth.

Waiting periods, red flag laws and other proven common sense safety regulations are long overdue.

The Iowa legislature will do nothing . . . but offer thoughts and prayers after the next tragedy.

Bill Bumgarner Sat 6 Jan 8:38 PM

we have these problems because the people in charge aren't moved by these sorts of arguments and they win elections

seems likely the state will force insurance companies to cover arming staff and allow parents and all to bring guns into school parking lots in this upcoming session, no?

dirkiniowacity Sun 7 Jan 12:04 PM