For weeks, Governor Kim Reynolds told reporters at her daily news conferences that “data” and “metrics” informed her approach to slowing the spread of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) in Iowa.

That narrative flew out the window on April 27, when she unveiled her plan to lift some mitigation measures statewide and allow many kinds of businesses to reopen in 77 Iowa counties, effective May 1.

Reynolds and Dr. Caitlin Pedati, the state medical director and epidemiologist, sought to spin the new policy as “evidence-based.” In reality, they are betting Iowans’ lives on the potential for data collection that has barely begun.

MOVING AWAY FROM “AN AGGRESSIVE MITIGATION STRATEGY”

A few minutes into her April 27 news conference, Reynolds touted her steps “to protect Iowans during an unprecedented time.”

However, this level of mitigation is not sustainable for the long term, and it has unintended consequences for Iowa families. So we must gradually shift from an aggressive mitigation strategy to focusing on containing and managing virus activity for the long term, in a way that allows us to safely and responsibly balance the health of our people and the health of our economy.

Reynolds noted that Iowa “has specific locations where virus activity is widespread” as well as areas where COVID-19 “is sporadic, and other locations where there is no activity at all.”

Narrator: that we know about.

For the governor, the uneven spread of COVID-19 across the state means “we can take a targeted approach to loosening restrictions on businesses in counties where there is no virus activity” or where case numbers have been “consistently low” and on a “downward trend.”

The proclamation issued the same day continues many mitigation policies (such as closures of theaters, casinos, hair salons, museums, and playgrounds) through May 15 but “loosens social distancing measures in 77 Iowa counties effective Friday, May 1.”

In the 77 counties, the proclamation permits restaurants, fitness centers, malls, libraries, race tracks, and certain other retail establishments to reopen in a limited fashion with public health measures in place.

Reopened businesses will be required to limit customers to 50 percent of their typical capacity. (I would welcome insight from people in the hospitality industry on whether restaurants can operate profitably under those conditions.) Other restrictions include spacing out exercise equipment at gyms, prohibiting fitness classes larger than ten people, and keeping children’s play areas closed at shopping malls.

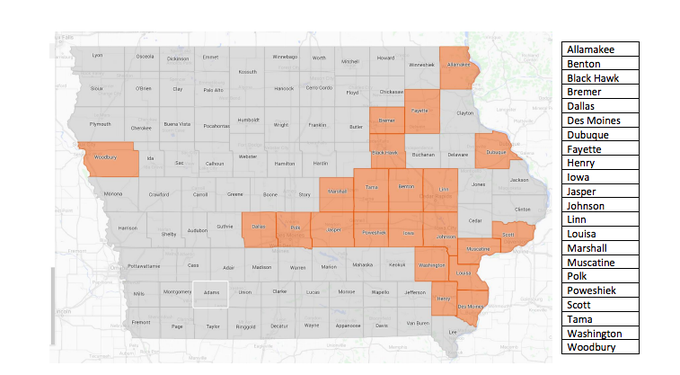

The 77 counties are gray on this map, which Caroline Cummings of Sinclair Broadcast Group helpfully posted on Twitter. Most restrictions on business and recreation will remain in effect for the counties marked in orange and listed to the right. A little more than half of Iowans live in the 22 orange counties.

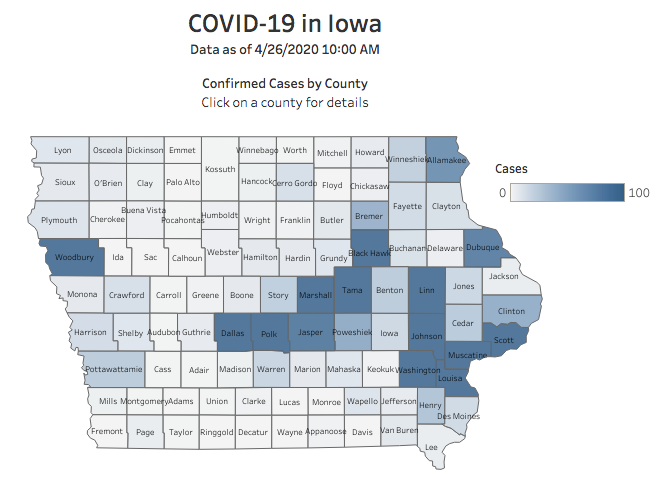

The counties where Reynolds continued most mitigation measures either have many confirmed COVID-19 cases or border counties with large outbreaks, shown in darker blue on the state’s official coronavirus website.

THREE RESTRICTIONS TO BE RELAXED STATEWIDE

The governor’s latest order allows elective surgeries to resume, even though the Iowa Department of Public Health has instructed health care providers to reuse some personal protective equipment that was designed for a single use. Because of the PPE shortage, I anticipate some hospitals will decline to schedule elective surgeries until after Iowa’s COVID-19 infections have peaked. On the other hand, such procedures are a money-maker for hospitals and especially for outpatient clinics.

After Reynolds previewed parts of her plan on April 24, Dr. Megan Srinivas, an infectious disease specialist in Fort Dodge, told Bleeding Heartland,

Throughout Iowa, including in western Iowa, we already have a PPE shortage and health care workers are being required to use protective gear repeatedly, which was never how PPE was intended to be used. If we re-open, we are going to have a further drain on this limited supply. This puts everyone at higher risk for COVID infection.

The governor is also allowing farmers’ markets to operate, provided they give space only to food vendors and take other steps to promote social distancing. Whether all markets will open this summer remains unclear. The city of Des Moines has not yet issued a permit for its downtown market, which typically attracts large crowds, beginning the first Saturday morning of May.

Iowa Senate Minority Leader Janet Petersen said in a statement, “Iowans don’t want to be used as guinea pigs.” With the state “experiencing staggering daily infections” and “record-high deaths,” it’s “not the time to try to make people happy by randomly reopening segments of the economy like crowded farmers markets.”

Finally, Reynolds is exempting religious groups from the ban on social gatherings larger than ten people. She explained at her news conference that she took the step “recognizing the significant constitutional liberties involved.”

Her proclamation states that houses of worship or hosts of spiritual or religious gatherings “shall implement reasonable measures […] to ensure social distancing of employees, volunteers, and other participants, increased hygiene practices, and other public health measures to reduce the risk of transmission of COVID-19 consistent with guidance issued by the Iowa Department of Public Health.”

Nevertheless, the gesture to Christian conservatives will likely accelerate the spread of the virus. Dr. Eli Perencevich, an infectious disease specialist and epidemiologist at the University of Iowa, highlighted two reasons attending a religious service is more dangerous than, say, grocery shopping. Exposure to a person carrying the virus for more than 30 minutes “is a huge risk factor. You don’t stand next to someone in a grocery for 60 minutes.”

In addition, “Singing releases a huge number of droplets. Singing in choirs/church is a very high risk activity for spread.” Perencevich linked to an article about a early March choir practice in Washington state that led to dozens of COVID-19 cases and at least two deaths.

I hope most religious organizations will realize it’s wiser to hold services and Bible study online for the foreseeable future. Regular church-goers are more likely to be in age cohorts at elevated risk of dying from COVID-19.

WHY NOW?

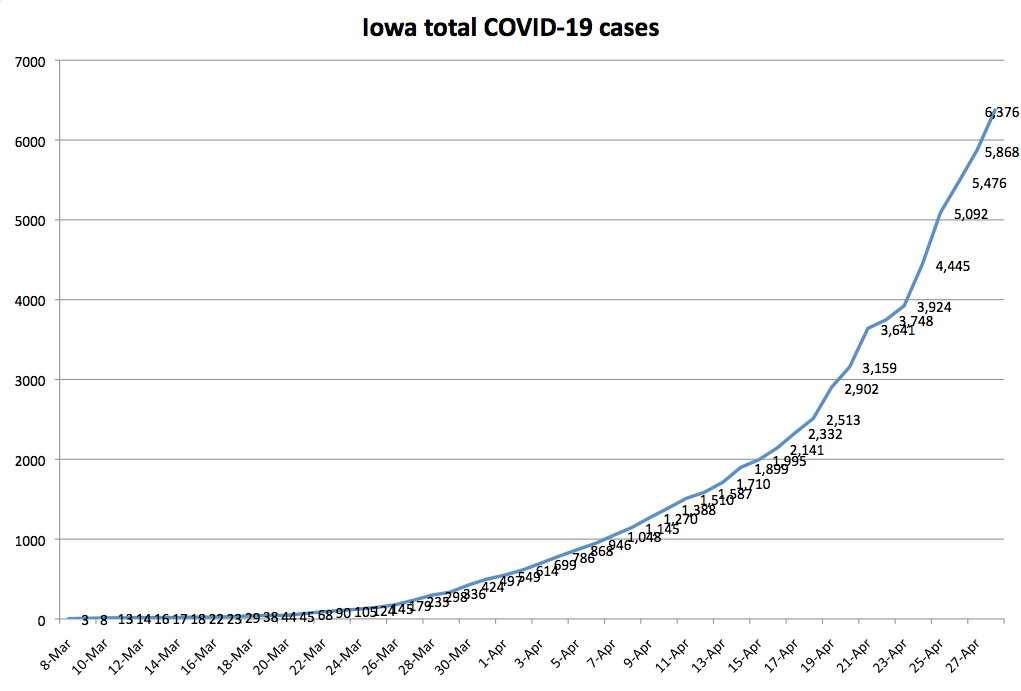

The timing of Reynolds’ latest proclamation is a head-scratcher. Weeks ago, the governor indicated she wouldn’t relax mitigation policies until COVID-19 infections had peaked (which IDPH officials incorrectly predicted would happen in late April).

The state’s Public Health Deputy Director Sarah Reisetter first asserted that Iowa’s curve was flattening on April 9. Reynolds alluded to that supposedly promising trend during her April 13 media availability, adding, “These signs are encouraging, but they are not a reason enough for us to let up on our mitigation efforts at this time.” She said cases and deaths were on track to increase until late April. “I want to open up this state as soon as we can, but I want to do it in a responsible manner. We don’t want to open it up, just to have to shut things back down again.”

On April 24, Reisetter speculated that COVID-19 infections would peak in Iowa in two to three weeks, and Reynolds announced what was then the highest number of newly confirmed cases and deaths for a single day. Yet minutes later, the governor described what she called an “opportunity to start to open Iowa back up in a phased and responsible manner.” She thanked “every Iowan for making our comeback possible. Today we’re taking the first steps to get life and business back to normal.”

What “comeback”?

In retrospect, it seems clear that regardless of the statewide trend, Reynolds was determined to start scaling back restrictions on May 1.

“JUST HANG WITH US FOR TWO MORE WEEKS”

In a recent post called “The Iowa COVID-19 peak that wasn’t,” I included Reynolds’ closing remarks from her April 17 news conference to illustrate the mixed messages that have become a staple of her public comments.

Only one day earlier, Reynolds had issued an order limiting “social, community, recreational, leisure, and sporting gatherings” for fourteen northeast Iowa counties to “people who live together in the same household.” At every media appearance that week, she had urged Iowans to stay home as much as possible.

But she ended that April 17 news conference on an upbeat note.

And while this has been a really tough week, I want you to know there are a lot of really positive signs out there as well. And this team is not only working hard to make sure that we’re taking care of vulnerable Iowans, not overwhelming the health care system, and really making sure that we flatten the curve.

But we also every day are looking at ways that we can open it back up, this economy, and let Iowans get out there and do what they do so well.

So, hang in there, there’s, you know, it’s been a tough week, but there’s also a lot of positive signs that we’re seeing out there. So if you just hang with us for two more weeks and be responsible, and stay at home if you’re sick, only go out for essential services, work from home if you can, and really do your part, then we’ll do our part, and we’re going to get Iowa opened up again. So thank you, I appreciate that.

Two weeks from April 17 happens to be May 1. It would be useful to know when the governor settled on that date.

One thing’s for sure: Reynolds and her advisers weren’t guided by modeling of COVID-19 spread in Iowa under different social distancing scenarios.

“IN THE PROCESS OF REVIEWING THE MODEL”

Epidemiologists routinely use statistical modeling of disease spread to evaluate mitigation policies. The IDPH team led by Dr. Pedati developed a bizarre twelve-point scale instead.

Reynolds and Reisetter (who had no public health background before landing her current job) have periodically cast doubt on the value of modeling, saying a model is only as good as the assumptions plugged into it. In contrast, Reisetter told reporters on April 13, “every recommendation that we’ve been making has been based on what is actually happening here in Iowa.”

State officials signed a contract with the University of Iowa’s College of Public Health on April 7, Ryan Foley reported for the Associated Press.

The contract calls for a model that will predict the number, severity and timing of future infections, hospitalizations and deaths. The model would be modified to predict how shifts in strategies, such as a stay-at-home order, might change public health outcomes.

The contract says the model is intended for use by the department “internally with other state agencies to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic.” It bars the university from publishing any findings before April 2021 unless approved by the state epidemiologist.

Barbara Rodriguez reported on April 27 that the University of Iowa researchers had delivered a report to the state.

Joe Cavanaugh, head of the biostatistics department at the university’s College of Public Health, told the Des Moines Register that the report given to the Iowa Department of Public Health includes “Iowa-specific models” using data from publicly available sources.

Cavanaugh confirmed the report’s existence to the Register on Thursday afternoon [April 23]. The Register has since made multiple requests to IDPH for the report, which has not been made public.

It’s unclear how long state officials have had the report. Pat Garrett, a spokesman for Reynolds, said on Monday morning in an email that the governor’s office and state public health officials are “in the process of reviewing the model and plans to share this information with the public.”

Some leaders would have analyzed the model before committing to roll back COVID-19 mitigation across much of the state. Then again, research has never been Kim Reynolds’ strong suit.

Reisetter downplayed the importance of the model when asked about Rodriguez’s reporting during the governor’s April 27 news conference. To hear her tell it, IDPH received a “white paper” from university researchers “early last week.” But “It wasn’t based on Iowa-specific information. That’s the third phase of the project. So we don’t have those results yet.”

Cavanaugh told Foley “his team has submitted two reports to the state that project the pandemic based on other models and publicly available data.” He also said “the work was done outside the scope” of the contract with the state (under which IDPH was to provide data to the researchers for use in developing a model). The university’s attorneys are considering whether it can be released under Iowa’s open records law.

UPDATE: The governor’s office provided both documents to the Des Moines Register. I’ve enclosed them at the end of this post. The researchers identified “a huge range of possible outcomes, from relatively low fatalities to catastrophic loss of life.” Given the “considerable uncertainty” in how many deaths Iowa could have (from 150 to more than 10,000), they recommended that “prevention measures should remain in place. Without such measures being continued, a second wave of infections is likely.” In the second report, they found the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) model for Iowa was “in line with plausible epidemic outcomes,” but that “a substantial risk of more severe spread remains,” and “It is far more likely that the model is underestimating the death toll than it is that the model is overestimating the death toll.”

If not modeling, what convinced Reynolds that “it’s time” to start opening things up?

“TESTING…ALLOWS US TO MAKE EVIDENCE-BASED DECISIONS”

The IDPH recently broadened testing criteria to allow for “surveillance testing” including some asymptomatic people living or working in settings with known COVID-19 outbreaks. Meanwhile, the state signed a $26 million no-bid contract with Utah-based companies to create a “Test Iowa” initiative.

Experts agree that mass testing is a necessary component of any plan to reopen the U.S. economy.

Reynolds and the state’s epidemiologist have apparently concluded that the potential to test more Iowans for COVID-19 is enough.

Considering that only about 250 people were tested at the first site in Des Moines this past weekend, I was surprised to hear Reynolds declare at her April 27 news conference,

Expanding testing is a significant advantage that we have in Iowa. Many states don’t yet have the capacity to test more of their citizens. Currently, on a per capita basis, one in every 82 Iowans have been tested for COVID-19. And soon we’ll continue to be be able to expand our testing, for up to 3,000 more Iowans a day, once all of the test sites are open and at full capacity. And that’s on top of what we’ll be able to do, that we’re already doing.

Testing, as I said, is another tool that allows us to make evidence-based decisions about how to mitigate and manage the virus with precision, whether at a macro level or down to a specific county, community, or zip code.

With the reality is, that we can’t stop the virus, that it will remain in our communities until a vaccine is available. Instead we must learn to live with COVID virus activity without letting it govern our lives.

We’re a long way from conducting an extra 3,000 tests per day. So far, the Test Iowa assessment prioritizes health care workers. Others are unlikely to qualify, even if they have symptoms suggestive of coronavirus.

Reynolds said a drive-through testing site will be set up this week in Waterloo (where a Tyson pork plant spawned a huge outbreak). But that’s nothing like the breadth of testing you would need to “manage the virus with precision” across Iowa, or even state with confidence (as Reynolds did repeatedly) that COVID-19 is not present in fifteen counties that have no confirmed cases.

Richard Lindgren lived in Decatur County for many years. He commented on Twitter,

This is all wishful thinking by @IAGovernor. If you only test the sickest you keep the numbers down. Should be true random testing in the zero-case counties like Decatur. With only 8500 pop, if you blitzed in with 100 tests you would have a statistically-significant sample. ->

— When God Plays Dice (@RKLindgren) April 27, 2020

Srinivas, the infectious disease doctor in Fort Dodge, told me she was “very concerned” about Reynolds’ reopening plan.

We do not have sufficient data nor is adequate testing being done to generate the data needed to safely re-open at this time. The Harvard study released last week demonstrated that we needed to increase our testing capacity to at least 150/100,000 people before we could safely consider re-opening. We’re not at that point. Additionally, we haven’t peaked in cases or deaths per several reputable models. Re-opening prior to peaking only drives our curve higher and endangers more lives.

If Iowa were administering some 4,650 COVID-19 tests each day, we’d be at the level of about 150 tests per 100,000 residents. We’re not close to collecting that much data yet. Also, the Harvard study calls for casting a wider net.

In most states, people who had severe symptoms, worked in health facilities or were otherwise hospitalized were given priority for testing. The goal of the testing level recommended by the [Harvard] researchers would be to test nearly everyone who has mild or severe flulike symptoms, and an average of 10 contacts for each person who tests positive for the virus.

The State Hygienic Laboratory’s criteria do not currently permit all sick Iowans to be tested. Even with symptoms, people need to be hospitalized, over age 60 with underlying conditions, living in a congregate setting, or part of the essential workforce.

Reynolds assured reporters that areas with increased virus activity will remain closed. “We’re learning more all the time,” and “as we’re able to do additional testing and the case investigation and contact tracing,” IDPH will be able to respond rapidly to a cluster of COVID-19 infections and “hopefully get in front of it, and not see a huge spike in the numbers.”

That’s a good goal, but we weren’t able to stop big outbreaks in Woodbury, Black Hawk, and Polk counties. How can the governor be so sure we can get ahead of the next clusters?

“WE’RE ADDING NEW TOOLS AND RESOURCES ALL THE TIME”

It’s bad enough for Reynolds to over-sell the Test Iowa program. Seeing the state epidemiologist push the same line was more disturbing.

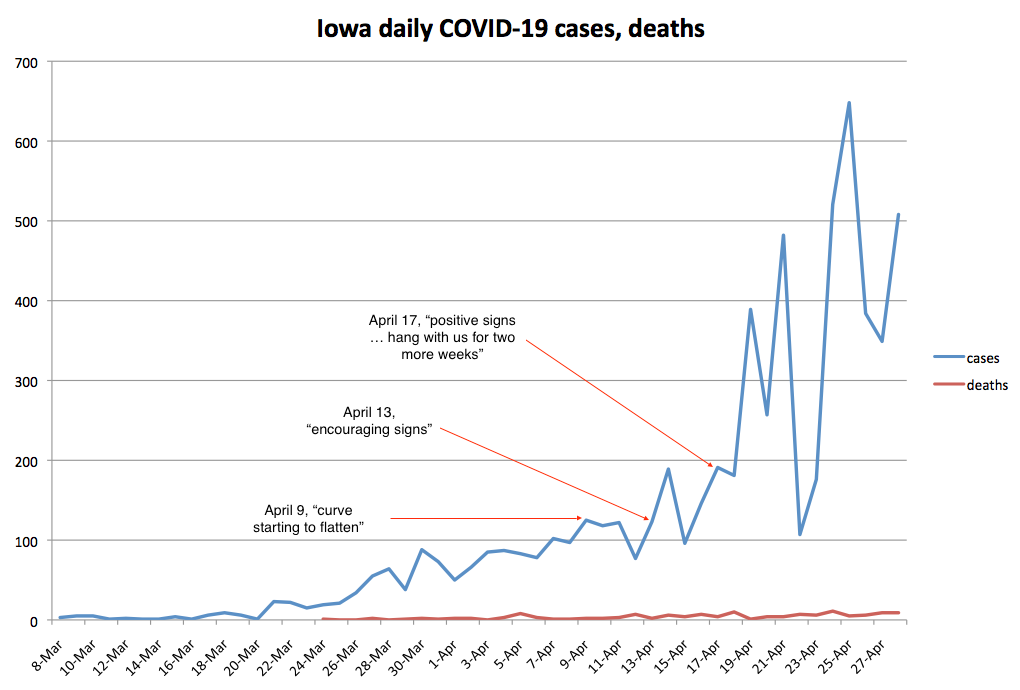

In this clip from the April 27 news conference, Adam Carros of KCRG-TV noted that officials had said Iowa’s curve was flattening on April 9. But symptoms onset and confirmed COVID-19 cases have spiked since then. “Do you still see a flattening of the curve happening? […] And what has changed to give you the confidence now that the data you’re looking at is accurate?” Reynolds thanked Carros for the question and immediately turned it over to Pedati.

I transcribed the doctor’s entire response, a master class in how to speak at length, deliberately and confidently, without getting around to answering the question.

Yeah, so I think you’re highlighting a couple of great ways that we’re able to look at information over time. We’re able to understand how trends can change. And it’s helpful to look at these things not just on a statewide level, but at a more, you know, maybe regional or community or county level, right?

And so I think that what Iowa has seen with our trend in cases over time is similar to what many states have seen, in terms of the activity. And where we start to see as we’re expanding testing resources, we’re able to identify additional cases, and we’re able to implement control measures in a more targeted way.

And so we continue to follow that information every day. It continues to be impacted by things like new resources and new tools that we’re implementing all the time as part of this public health response. And it’s an important thing for us to follow. It’s one of the many things that we follow to understand trends and what’s going on.

And because we’re adding new tools and resources all the time, we’re increasingly able to look at that quicker and at a more local level, so that, when we do notice something that may be driving a particular increase–whether it’s associated with a long-term care setting, a particular community or household, or other sort of congregate situation–we’re able to provide targeted resources and support to public health and clinicians and communities in those areas.

Does Pedati still think Iowa’s curve is flattening? She didn’t say.

Why is she confident the department now has an accurate snapshot of virus activity around Iowa? She didn’t say.

Nor did she admit that IDPH officials were wrong to suggest weeks ago that we were turning the corner, based on our state’s “epi curve.”

About that curve…

SYMPTOMS ONSET DATA NOT FLATTENING

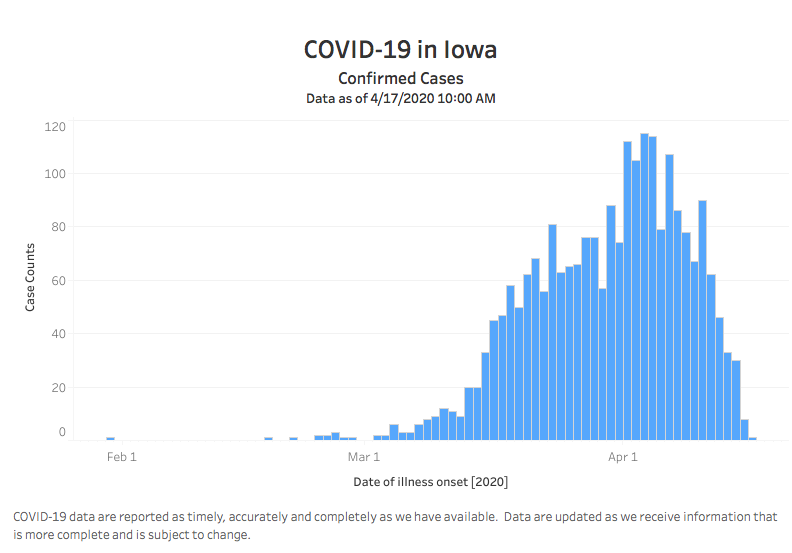

As newly confirmed case numbers rose in early April, exceeding 100 several days in a row, Reisetter told reporters on April 9 that the epidemiological curve “is starting to flatten, which means that Iowans are listening.” The next day, she elaborated,

So what we have been looking at is we’ve been looking at onset of symptoms data. So while, you know, the positive case results–and we have said all along that we anticipated last week was going to be a difficult week in terms of cases.

Again, at the beginning of this week, we said we were going–we fully expected to see our case numbers start to climb.

But when we look at our onset of symptoms data, that appears to be flattening. And that’s, that’s really the whole goal of public health mitigation efforts, is to see a flattening. […]

And so that’s what I was referencing is we’re looking at the epi curve related to onset of symptoms. And that curve appears to be looking fairly flat at this particular point in time. Which is why it is so important for the public to continue to do all of the things that they have been doing. […]

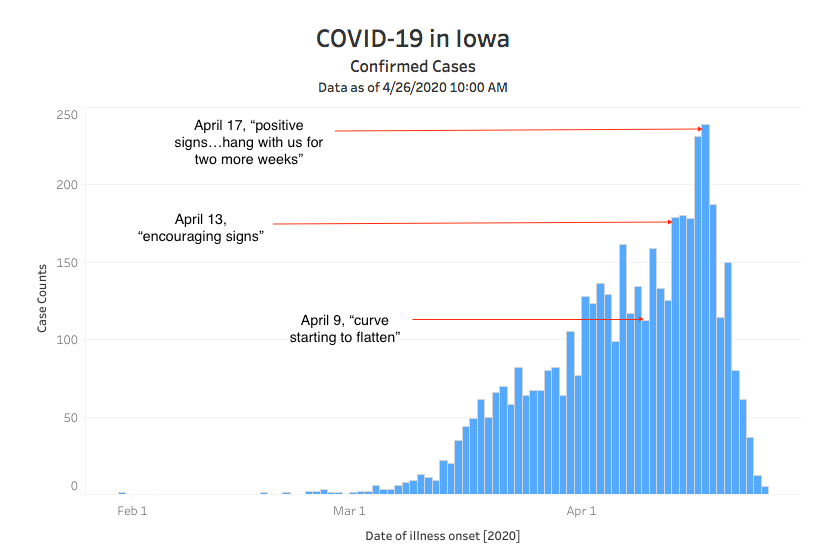

Here is the epi curve with data through April 17, the day the governor urged Iowans to “just hang with us for two more weeks.”

As Bleeding Heartland discussed here, a casual observer would think new cases started dropping off around April 10. You have to read the fine print to learn that this graph displays “date of illness onset.” Srinivas explained, “Since most people don’t seek care until a few days after initial appearance of symptoms, the most recent few days are going to be skewed and look disproportionately low.”

Indeed, now that we’ve filled in ten more days of data, you can see that Iowa cases, as measured by symptoms onset, increased sharply after April 10. This is the latest epi curve, as displayed on April 27. Note that the “y” axis goes twice as high as it did ten days ago.

The curve still creates the impression that newly confirmed cases have been declining since April 17. But this graph doesn’t show the date a given number of Iowans tested positive. It shows the date they reported they started feeling sick. People who were just infected and may not have symptoms or haven’t gone to the doctor yet won’t show up on this curve.

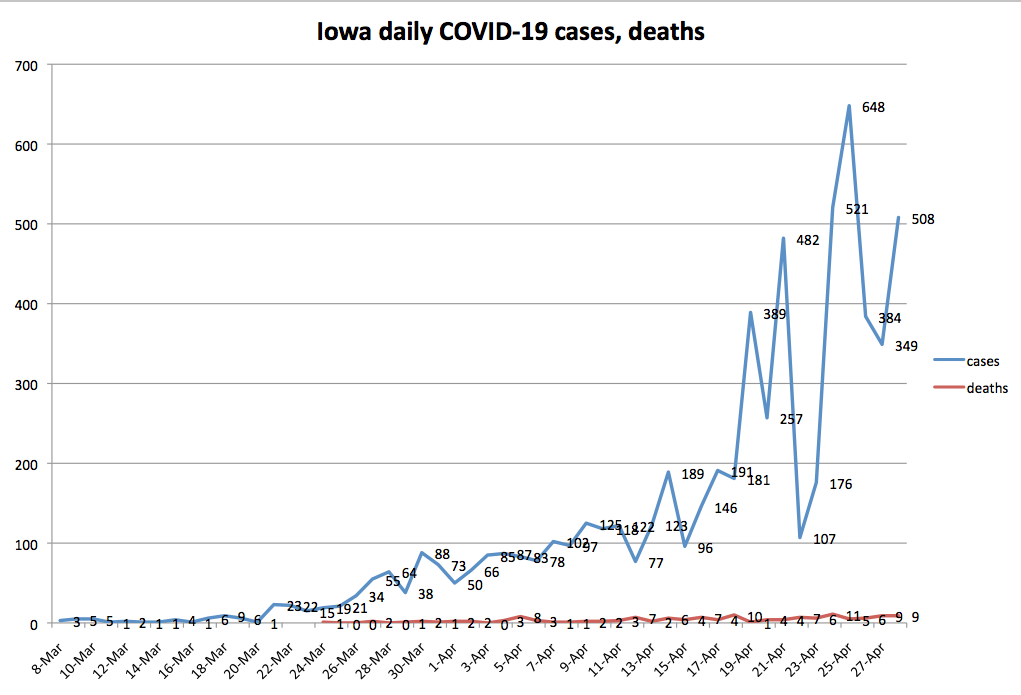

I created this chart using the numbers of new COVID-19 cases the IDPH has confirmed each day. You don’t have to be an epidemiologist to see our curve is not flattening.

But let’s see what an epidemiologist has to say.

Make no mistake, IDPH and Governor have made a tragic error. By misreading Iowa’s “symptom onset” epidemic curve, they’ve been incorrectly thinking the curve is flattening, when it is actually increasing.

Iowa opening up at the exact wrong time. Needed to wait 10-14 more days

— ??? ??????????? ? ? (@eliowa) April 28, 2020

Unfortunately, infections seem to be spreading faster in Iowa than in many other states. This interactive tool from the New York Times Upshot team shows that three of the six U.S. metro areas where the virus is spreading most rapidly are in Iowa: Sioux City (number 1), Waterloo/Cedar Falls (2), and Des Moines (6).

Meatpacking plant outbreaks are responsible for most of the COVID-19 cases in the Waterloo and Sioux City areas, which should set off alarm bells in much of western Iowa.

MEATPACKING PLANTS SCATTERED ACROSS THE REOPENING COUNTIES

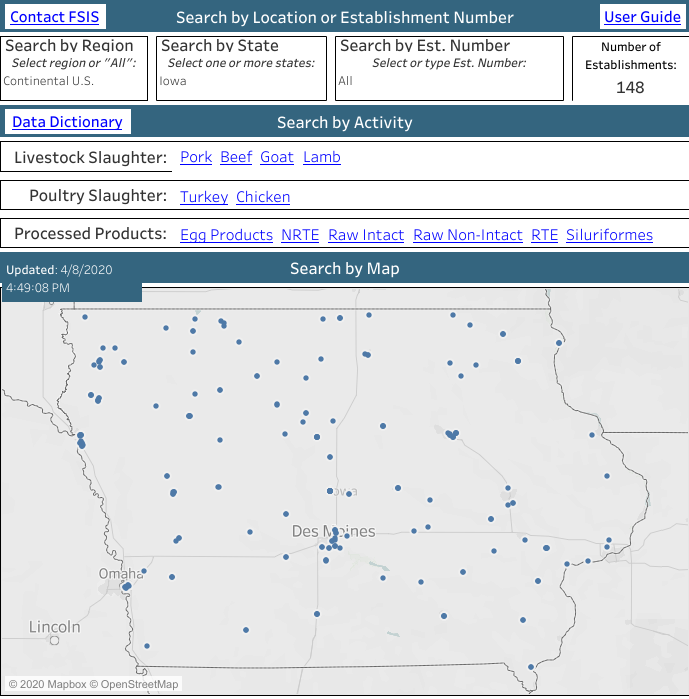

The blue dots on this map represent Iowa food processing facilities (primarily beef, pork, poultry, and eggs) that are subject to regulation by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. This is a screen shot; you can find the interactive version on the USDA’s website.

Look how many of those blue dots are in the gray counties, where Reynolds is lifting some of the COVID-19 mitigation measures.

In per capita terms, Tama and Louisa counties are experiencing huge coronavirus outbreaks that started in meatpacking facilities. What separates them from western counties like Crawford or Buena Vista or Sioux, where meatpackers are major employers?

Also worth mentioning: The Tyson plant in Perry (Dallas County), which recently closed for a few days due to a COVID-19 outbreak, is close to both Greene and Boone counties. How many workers at that facility live in counties that are about to open up?

Srinivas commented,

Western Iowa has potential to have an uptick in cases in the coming days. Prestage, a meat-packing facility in this area [Wright County], had a small outbreak earlier this week and we’ve seen several more people reporting symptoms and requiring testing. And that’s very early in the 14 day incubation period of the virus, so we’ll likely see more patients with symptoms coming forward in the next week to 10 days. Stating that western Iowa is safe from the virus in the midst of this recent spate of cases is very concerning.

NO ANSWER ON TRAVEL BETWEEN “OPEN” AND “CLOSED” COUNTIES

WHO-TV’s Dave Price wondered, what if people leave the closed areas to go out to eat or shop in a different county, and accidentally spread the virus. “People have to be responsible,” Reynolds said.

Chris Gothner of KCCI-TV returned to the topic later, asking Pedati, what makes you think that a patchwork opening of some counties will keep the disease from spreading? Reynolds jumped in to answer. “It’s based on a stabilization” of virus activity and the number of cases over the past fourteen days, she said. Again, the governor spoke as if Iowa already had a testing regime fully engaged, delivering results from every county.

Because of the additional tools that we have, we are now able to really drill down and look at the virus activity, from a state perspective, from a regional perspective, to a community perspective, and eventually, right down to the zip code. […]

As I said earlier, too, there are fifteen counties that have had no activity whatsoever. [Narrator: that we know about.]

And so they are at a place where we can start to, in a very responsible and safe manner, start to open up the counties and start to open up the state.

And I have confidence in Iowans that they are going to continue to be a part of the solution. They are going to continue to do the right thing. And we’re going to continue to see, hopefully, positive signs of that, and we’ll be able to continue to build on what we’re already doing.

Pedati stepped up to the lectern again, speaking generally about public health efforts to control disease outbreaks: collecting information, identifying people at risk, and implementing mitigations. She often puts COVID-19 in the context of other respiratory illnesses, which may be a way to burn time, or may be a tactic to convey that she is on top of this situation.

Which again, as we understand more about this virus–and we still have more to learn–but what we do know, again, is that this is spread from one person to the next when they’re in close contact with each other, which is similar to what we’ve seen from other types of respiratory pathogens.

And like other respiratory pathogens, we often see differences in regions, particularly around populations or places where people gather, so congregate settings.

Speaking of congregate settings, every Iowa county has at least one nursing home. Visitor restrictions will remain in effect for the time being, but staff could spread the virus, or it could arrive along with a patient discharged from the hospital. The number of long-term care facilities with confirmed outbreaks just jumped from sixteen to 23 in one day. About half of the 136 Iowans who have died in the pandemic lived in nursing homes.

Back to Pedati, who sure has a lot of faith in “tools and resources.”

And so again, we use the information we have so far and what we know about the virus and how it behaves. We integrate that with what we know about who’s at highest risk. And that helps us to drive our control measures, which we’re able to do at varying levels in more targeted ways as we gather additional tools and resources.

And it’s again an example of a place where I think public health in general remains flexible as we get more information, and more of these tools and resources, and we’re going to continue to adjust, just like we would with the flu season or any other illness that public health professionals work to protect Iowans against.

The stakes are a lot higher here than when the IDPH adjusts during a regular flu season.

NO ANSWER ON ASYMPTOMATIC SPREAD

In the context of learning to live with the coronavirus, Reynolds “strongly” encouraged “all vulnerable Iowans,” including those with pre-existing conditions or over age 65, “to continue to limit their activities outside of their homes.” She asked all Iowans to “stay home if you’re sick.”

Erin Murphy of Lee Newspapers wanted to know, isn’t there a risk that asymptomatic people could spread COVID-19 from counties with many cases to those where more businesses are open? Pedati answered and began with a compliment, as usual.

Yeah, it’s a great question. And again, it’s an example of a place where I think as we learn more about this virus and its behavior, we’re able to better target our interventions and resources.

And so if somebody has been exposed and isn’t showing symptoms, so an asymptomatic person, that’s an example of a person public health would be recommending that they stay in their home for fourteen days, in order to limit the spread of the virus.

And so again, by using our public health tools and skills of case investigation and contact tracing, we’re going to try and be very targeted about the people who we think are at risk, the people who have been exposed. And again, our commitment remains to making sure that we stop the spread of this virus as much as possible, support our vulnerable Iowans, and share as much information as quickly as we can.

How would these asymptomatic people know they had been exposed? Why would it occur to them that they should isolate for fourteen days? How would they ever get to the point of being tested for COVID-19, let alone case investigation or contact tracing? Iowa’s current policy does’t even authorize a coronavirus test for everyone with symptoms.

The governor and state medical director are taking a huge leap of faith and dragging the rest of us along with them. I wouldn’t bank on COVID-19 infections peaking here anytime soon.

_________________________

Appendix: Documents prepared by the University of Iowa research team for the Iowa Department of Public Health

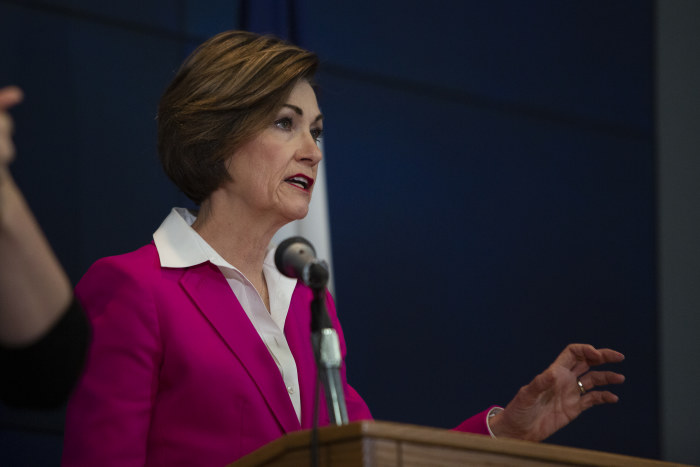

Top image: Governor Kim Reynolds speaks during a news conference on April 27, 2020. Photo by Olivia Sun/Des Moines Register, pool.

2 Comments

Why now?

Because word has gone out from the super secret Message Manager that all Republicans SHALL say 1 it’s not no dangerous after all and 2 it’s time to get back to work. I hear it from Hannity, Reynolds and my cousin Gail. Public safety, what an old fashioned concept.

John Whiston Tue 28 Apr 6:58 PM

Excellent summary, thanks for providing it!

An insightful point of view was also presented by Kathie Obradovich of the IOWA CAPITAL DISPATCH in a post titled “It’s the perfect time to reopen Iowa — politically speaking.” Here’s an excerpt:

“So what makes this the perfect time to start reopening the state? The ramp-up of testing is expected to lead to an increase in positive cases. The reopening of the state, regardless of how carefully it’s done, will also likely lead to an increase in positive cases as people return to work and begin to gather again outside their homes.

How many cases can be attributed to mingling at farmers markets versus an increased level of testing? How many cases might result if certain types of businesses are open starting May 1? We’ll probably never know. And if we don’t know, it will be harder to pin blame for more sickness and deaths on decisions to reopen the state.”

Sounds about right.

PrairieFan Wed 29 Apr 12:08 AM