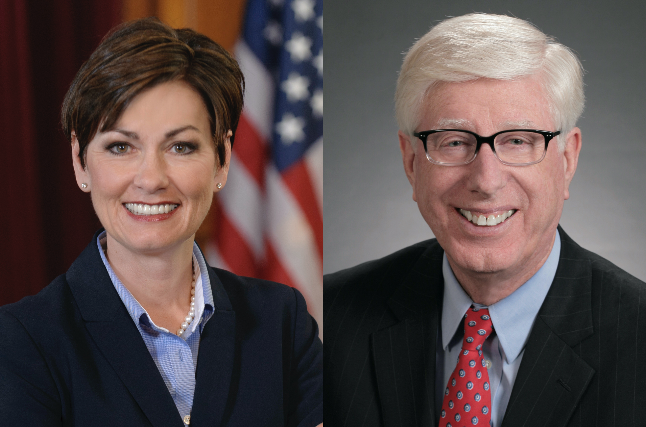

Governor Kim Reynolds denied 35 requests to sign Iowa on to multi-state legal actions during the first year of an unusual arrangement in which Attorney General Tom Miller ceded some of his authority.

Reynolds refused to allow the state to weigh in on lawsuits related to federal or state policies on immigration, reproductive rights, environmental regulation, consumer protection, gun safety, LGBTQ rights, and access to President Donald Trump’s personal records.

During the same time frame, the governor approved eighteen requests from Miller to join cases involving a wide range of legal matters.

The two officials struck what Miller called a “good-faith agreement” in May 2019 as a condition of Reynolds vetoing part of a bill that would have permanently constrained the attorney general’s power, and that of his successors. Under the deal, Miller retained his ability to join multi-state letters and investigations but promised

he will not prosecute any action or proceeding or sign onto or author an amicus brief in the name of the State of Iowa in any court or tribunal other than an Iowa state court without the consent of the Governor. He retains the authority to participate in litigation or author letters in his own name, as Attorney General of Iowa.

No other state attorney general operates under similar constraints.

Miller acknowledged last year that the deal meant “generally I will not be suing the Trump administration.” Reynolds has consistently refused to allow Iowa to join any lawsuit or amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) brief opposing a federal policy.

Draft legal filings and correspondence between staff for the attorney general and the governor’s senior legal counsel, Sam Langholz, are largely exempt from Iowa’s open records law, which shields attorney-client communication and attorney work product from public view.

But in response to Bleeding Heartland’s request, communications director Lynn Hicks compiled a summary of lawsuits and amicus briefs the Attorney General’s office forwarded to the governor’s office. That document, enclosed at the end of this post, lists all requests through last week, the anniversary of the compromise that secured Reynolds’ item veto.

REQUESTS DENIED

The cases where Miller would have joined multi-state efforts, if not for the governor’s objection, fall into seven categories.

Humane treatment and due process for immigrants, asylum seekers

Miller sought to join amicus briefs in nine cases that challenged Trump administration policies toward immigrants and asylum seekers. Reynolds said no every time.

If Miller were able to freely exercise the authority Iowa Code provides to the attorney general, the state would have joined a brief supporting the plaintiffs’ motion for summary judgment in U.T. v Barr. They were challenging a federal rule that bars humanitarian relief for asylum seekers from the “Northern Triangle countries” (El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras).

In two cases, Miller wanted to advocate for preliminary injunctions blocking the U.S. Department of Homeland Security from applying the Third Country Transit Rule, which bars asylum for applicants who traveled through another country en route to the U.S. without applying for asylum there ( Al Otro Lato v. Wolf and East Bay Sanctuary Covenant v. Barr).

Plaintiffs in Grace v. Barr challenged a Justice Department decision to deny most asylum claims based on gang violence or domestic violence.

Similarly, Miller wanted to support plaintiffs challenging federal rules and a presidential proclamation that would make it harder for immigrants to obtain green cards and visas (MRNY v. Pompeo and John Doe #1 v. Trump).

Iowa was unable to take a stand against two Trump policies designed to increase deportations. One case involved the president’s decision to terminate temporary protective status for Haitians (Saget v. Trump). The other challenged a 2019 rule on “expedited removal,” which expanded fast-track deportations “without a fair legal process such as a court hearing or access to an attorney” (Make the Road New York, et al. v. McAleenan).

Finally, Reynolds showed little empathy for immigrant children kept in filthy warehouses last summer. Miller asked to sign on to an amicus brief in Flores v. Barr, seeking to enforce the 1997 Flores settlement agreement “requiring immigration agencies to hold such minors in their custody in facilities that are safe and sanitary.”

Reproductive rights

Eight cases involved access to abortion or contraception. Although Reynolds was sure to decline–after all, she did sign a near-total abortion ban later ruled unconstitutional–Miller kept asking.

Six of the cases were about state efforts to restrict abortion:

Federal rules were at the center of the other two cases in this category. Miller would have signed amicus briefs supporting the city of Baltimore’s challenge to “a rule that bars Title X family planning grantees from providing or referring patients for abortion” (Mayor & City Council of Baltimore v. Azar). He also would have backed efforts by the states of Pennsylvania and New Jersey to challenge exemptions to the contraception mandate in the 2010 Affordable Care Act (Trump v. Pennsylvania/ Little Sisters of the Poor v. Pennsylvania).

Environmental regulation

Seven cases fall into this group. Before Republican lawmakers and Reynolds acted to curtail his authority, Miller had worked with other states to oppose Trump rollbacks of the Clean Power Plan and other policies of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Last summer, Reynolds stopped Miller from joining a multi-state challenge to the EPA rule replacing the Clean Power Plan (New York v. EPA).

Around the same time, Miller sought unsuccessfully to sign a brief supporting plaintiffs in Union of Concerned Scientists v. Wheeler. They were challenging a new regulation that will prevent many academic scientists (but not corporate-funded ones) from serving on the EPA’s science advisory boards.

California sued to block a National Highway Traffic Safety Administration rule that pre-empted state regulations on greenhouse emission standards for cars and zero emission vehicles (California v. Elaine Chao). The state is also the lead plaintiff in a suit opposing a rule that rolls back “the greenhouse gas emissions and fuel economy standards for model year 2021-2026 passenger cars and light trucks,” according to Hicks (California v. EPA).

Miller would have signed a brief supporting the plaintiff challenging a Federal Energy Regulatory Commission practice used to block judicial review while pipelines are being built (Allegheny Defense Project v FERC).

Most recently, Reynolds prevented Iowa from joining New York’s lawsuits over the Refrigerant Management Rule under the Clean Air Act and the EPA’s decision not to enforce numerous monitoring and reporting requirements, citing the COVID-19 pandemic (both cases are called State of New York v. EPA).

Consumer protection

Reynolds rejected four requests in this area. Three of those decisions are not surprising. Miller wanted to support the U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which faces a lawsuit claiming that vesting substantial executive authority in the agency violates the separation of powers (Seila Law v. CFPB). Republicans have been trying to hobble that agency since its creation.

Plaintiffs in four consolidated cases are challenging “train crew staffing requirements and the preemption of state safety standards” (Transportation Workers v. Federal Railroad Administration). Republicans often side with business against such regulations.

The governor didn’t want Iowa to support student borrowers who are claiming they were erroneously denied loan forgiveness (Weingarten v. U.S. Department of Education). Reynolds is a big fan of Education Secretary Betsy DeVos.

The last case in this group is a head-scratcher. Miller would have signed a brief backing the Securities and Exchange Commission’s authority to use civil actions to try to recover money obtained through fraud (Liu v. SEC). Who’s against that?

Gun safety

Miller asked to join one multi-state lawsuit and three amicus briefs in cases related to firearms regulations, a non-starter for a governor endorsed by the National Rifle Association. In State of Washington et. al. v. U.S. Department of State, the plaintiffs are trying to halt rules deregulating 3-D printed guns.

Two briefs supported state authority to enact restrictions on large-capacity ammunition magazines (State of Vermont v. Max B. Misch and Duncan v. Becerra, a challenge to California’s ban).

The last case in this category was New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. City of New York, a challenge to the city’s ban (later repealed) on “transporting a licensed, locked and unloaded handgun to a home or shooting range outside city limits.”

LGBTQ rights

The first request Reynolds denied under her “good-faith agreement” with Miller happened last June. The attorney general wanted Iowa to sign a brief supporting the plaintiffs in three consolidated cases on whether Title VII (which prohibits sex discrimination) also bans employers from discriminating on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity. Last year, the governor’s staff did not answer my questions about whether Reynolds believes employers should be able to fire an employee or not hire an applicant after learning the person is gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender. Such action has been illegal under the Iowa Civil Rights Act since 2007.

Reynolds also refused to let Iowa sign a brief holding that it is discriminatory for a school to refuse transgender students access to common restrooms (Grimm v. Gloucester County School Board).

Access to Trump’s personal records

In Trump v. Vance, which was argued in the U.S. Supreme Court this month, the issue at hand is whether “a grand-jury subpoena served on a custodian of the president’s personal records, demanding production of nearly 10 years’ worth of the president’s financial papers and his tax returns, violates Article II and the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution.”

You can always count on Iowa Republican elected officials to do everything in their power to shield Trump from scrutiny. Naturally, Reynolds rejected Miller’s request to support the position taken by New York City District attorney Cyrus Vance.

CONSENT GIVEN

The document provided by the Iowa Attorney General’s office notes eighteen cases in which Reynolds agreed to multi-state legal actions.

State power

Six amicus briefs Reynolds approved could be characterized as efforts to assert state power in some way.

One defended an Arkansas law regulating reimbursement rates set by pharmacy benefit managers (Rutledge v. Pharmaceutical Care Management Association). Iowa has a similar statute.

Another supported efforts by Massachusetts to stay the federal Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s act to decommission a nuclear power plant (Massachusetts v. Nuclear Regulatory Commission).

One backed state Supreme Court rulings in Montana and Minnesota relating to jurisdiction over a non-resident corporation (Ford Motor Co. v. Montana Eighth Judicial District and Ford Motor Co. v. Bandemer).

One could reduce the number of lawsuits incarcerated individuals can file without paying court fees (Lomax v. Ortiz-Marquez).

Miller also wanted to support the idea that a state attorney general can pursue restitution against a defendant after “private litigants settle their claims against the same defendant” (Minnesota v. CenturyLink).

Finally, an amicus brief in a Minnesota case argued that sovereign immunity protects a state university against a certain kind of judicial review (Regents of the University of Minnesota v. LSI Corp).

Consumer protection

Four amicus briefs were about practices that harm ordinary people. One could argue that these cases were also about government power.

In North Dakota v. Purdue Pharma, Iowa supported North Dakota’s appeal of summary judgment in an opioid-related lawsuit.

The Pennsylvania v. Navient case “defends the states’ vital ability to enforce state and federal consumer protection laws against student loan servicers” that engaged in “various unfair and deceptive business practices.”

One brief supported the Federal Trade Commission’s action on “pay-for-delay” agreements between brand drug companies and generic rivals (Impax v. FTC).

Another argues that district courts can “enter an injunction that orders the return of unlawfully obtained funds” (Federal Trade Commission v. Credit Bureau Center, LLC).

Supporting agricultural interests

Iowa politicians from both parties have long opposed other states’ livestock animal welfare laws. So it was no surprise that Miller asked Reynolds to back the National Pork Producers Council’s challenge to a California ban on selling veal, pork, or eggs from “animals not raised in accordance with that state’s animal-confinement regulations” (National Pork Producers Council v. Ross).

The governor also agreed to support the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s decision to withdraw a rule on organic livestock and poultry practices (Organic Trade Association v. USDA).

Campaigns and elections

Miller made two requests in this area. Iowa signed a brief supporting the federal ban on robocalls (Barr v. American Association of Political Consultants), and one backing states that want to bind presidential electors to the state’s popular vote (Chiafalo v. Washington; Colorado v. Baca).

Multi-state settlements

U.S. Department of Justice v. Lehigh Cement Co. was a negotiated settlement for alleged air pollution violations. In the Endo case, Iowa received about $10,000 as compensation for “alleged anticompetitive conduct (pay-for-delay agreements) for the purpose and effect of obstructing generic competition for the branded drug Lidoderm.”

Protecting National Guard members

Iowa joined other states arguing that members of the National Guard are covered under the Uniformed Service Members Employment and Reemployment Rights Act, which prohibits discrimination against those “in a uniformed service” (Mueller v. City of Joliet).

Native American rights/tribal sovereignty

Reynolds agreed to let Iowa sign a brief that sought to preserve the the Indian Child Welfare Act’s provisions on adoptions (Brackeen v. Bernhardt).

Final note: Miller informed the governor’s counsel Langholz of 27 instances where other states invited Iowa’s participation, but the attorney general wasn’t interested in joining. Those cases are listed near the end of the document Hicks provided, under “Forwarded, but consent not requested.”

The governor’s office neither declined nor consented to one request after determining that Miller did not need Reynolds’ approval for an amicus brief signed by current and former attorneys general rather than by states. That brief argued that the Arizona attorney general can “represent the state as chief legal officer and sue the regents over a tuition increase,” Hicks explained.

Appendix: Document prepared by the Iowa Attorney General’s office summarizing requests to join lawsuits or amicus briefs through May 22, 2020.