Herb Strentz reviews current political divisions over examinations of systemic racism. -promoted by Laura Belin

Our nation’s long, tortured, and systemic racism was marked in late May by several commentaries and observances, which help explain why the adjectives “long,” “tortured,” and “systemic” are appropriate and, unfortunately, will likely remain so.

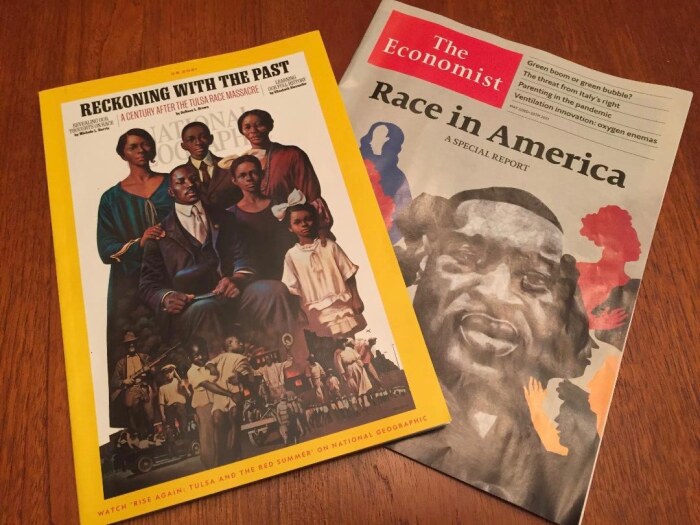

The June issue of National Geographic offered a centennial retrospective of June 1, 1921, when “a white mob massacred as many as 300 people in the prosperous Black district of Tulsa, Oklahoma.” The New York Times offered an interactive account of the massacre.

May 25 also marked the first anniversary of the murder of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The Economist, a British weekly, offered a cover story, commentary, and Special Report on Race in America. A provocative point made by The Economist’s statistics and analysis is “America is becoming less racist but more divided by racism.”

To be systemic, racism does not have to be manifested on a mass scale, as in Tulsa, or in the countless individual assaults or killings, like what happened to Floyd. A dictionary definition is “policies and practices that exist throughout a whole society or organization, and that result in and support a continued unfair advantage to some people and unfair or harmful treatment of others based on race.”

That describes pretty well what National Geographic, The Economist, and others are talking about.

When The Economist observed Americans are becoming “more divided by racism,” that dynamic is evident in how many conservatives and some state legislatures have reacted this year to examinations of structural racism.

The 1619 Project, a lengthy and continuing commentary about the impacts of slavery upon our society, led to a 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Nikole Hannah-Jones of the New York Times. It also led Republican state legislators around the country to try to limit public school use of curriculum guides from the project, supposedly because it painted a distorted picture of U.S. history.

Also under criticism is critical race theory, which deals with manifold causes of racism. Critics say the theory blames too many of us for racism. Hannah-Jones, who led the 1619 Project, now holds the Knight Chair in Race and Investigate Journalism at the University of North Carolina School of Journalism. Despite faculty and university recommendations, the UNC board of trustees denied a recommendation to grant her tenure, but approved a five-year contract instead.

In talking about Republican opposition to the project she spearheaded, Hannah-Jones told CNN, “If you look at the rhetoric of Senator (Mitch) McConnell and of state legislators all across the country that are trying to get bills passed to prohibit the teaching of the 1619 Project, it’s not about the facts of history. It’s about trying to prohibit the teaching of ideas that they don’t like.”

Hannah-Jones’ Iowa credentials (she grew up in Waterloo) did not spare her and the 1619 Project the wrath of some Iowa Republicans. State Representative Skyler Wheeler sponsored House File 222 to cut some funding for Iowa public schools and colleges if they used parts of the 1619 curriculum. At a House subcommittee meeting in February, Wheeler called the 1619 project “leftist political propaganda” and “revisionist history.”

“Of course the main argument in the project is that America is inherently racist, founded on slavery, racism and bigotry,” Wheeler said. “However that’s simply not true. America is the only majority-white country in the world to elect a Black president, and we’ve done it twice.”

The measure advanced from subcommittee on a party-line vote but did not clear the House Education Committee before the legislature’s first “funnel” deadline. It was therefore not eligible for debate on the House floor.

Those opposed to critical race theory, an academic approach to the causes of systemic racism, raise objections similar to those raised by critics of Project 1619.

Their take on it is summarized in a publication of Hillsdale College, a private conservative liberal arts college in Michigan:

Critical race theory is an academic discipline, formulated in the 1990s, built on the intellectual framework of identity-based Marxism. Relegated for many years to universities and obscure academic journals, over the past decade it has increasingly become the default ideology in our public institutions. It has been injected into government agencies, public school systems, teacher training programs, and corporate human resources departments in the form of diversity training programs, human resources modules, public policy frameworks, and school curricula.

A contrary view is found in the Sojourners magazine, a liberal Christian magazine that opposed Donald Trump’s presidency and is published by the American Christian social justice organization Sojourner.

The crux of the article by Kenyatta R. Gilbert, a professor at the Howard University School of Divinity in Washington, D.C., is summed up in fourteen words: “Critical theory is threatening only to those who are fighting to preserve white propriety.”

Academic and theological discourse differs from political rhetoric, which brings us to Mississippi Governor Tate Reeves and a predecessor, James K. Vardaman, governor from 1904-1908, and then U.S. senator.

For his part, toward the end of April, which he had proclaimed as Confederate Heritage Month, Reeves also declared, “There is no systemic racism in America,” and there is no systemic racism in the state’s administration of justice.

Those declarations would not sit well with Vardaman, who as a state legislator helped in the drafting of laws and adoption of a revised state constitution in 1890. He said at that time, “There is no use to equivocate or lie about the matter … Mississippi’s constitutional convention of 1890 was held for no other purpose than to eliminate the n*gger from politics.”

Systemic racism, anyone?

What gives me pause is not a quote from Reeves or Vardaman, but this from Thomas Jefferson. The quote is among those etched on the Jefferson Memorial — you know, that’s near the place of the January 6 insurrection:

“Indeed, I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just, that his justice cannot sleep forever. Commerce between master and slave is despotism. Nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate than that these people are to be free.”

And maybe racism need no longer be systemic.

Herb Strentz was dean of the Drake School of Journalism from 1975 to 1988 and professor there until retirement in 2004. He was executive secretary of the Iowa Freedom of Information Council from its founding in 1976 to 2000.

Top image: Photo by Joan Strentz of recent magazine covers provided by the author and published with permission.

No Comments