New restrictions on absentee voting prevented hundreds of Iowans from having their ballots counted in the June 7 primary election, Bleeding Heartland’s review of data from county auditors shows.

About 150 ballots that would have been valid under previous Iowa law were not counted due to a bill Republican legislators and Governor Kim Reynolds enacted in 2021, which required all absentee ballots to arrive at county auditors’ offices by 8:00 pm on election day. The majority of Iowans whose ballots arrived too late (despite being mailed before the election) were trying to vote in the Republican primary.

Hundreds more Iowans would have been able to vote by mail prior to the 2021 changes, but missed the new deadline for submitting an absentee ballot request form. More than half of them did not manage to cast a ballot another way in the June 7 election.

The new deadlines will trip up many more Iowans for the November election, when turnout will likely be about three times the level seen in this year’s primary, and more “snowbirds” attempt to vote by mail in Iowa from other states.

ABOUT 150 BALLOTS MAILED BEFORE ELECTION WERE TOSSED

For many years, mailed ballots could be counted in Iowa if they arrived by the Monday following election day, and the envelope was postmarked by the day before the election. Since the U.S. Postal Service doesn’t always attach postmarks, a law approved in 2019 required county auditors to order barcodes for absentee ballot envelopes. The concept was that the barcode could help election officials determine whether a late-arriving ballot had entered the postal system no later than the day before the election.

Republican wiped that away in 2021 by enacting many new restrictions on early voting. The law remains in effect as litigation challenging its constitutionality proceeds. A “sure count” deadline of 8:00 pm on election day now applies to all absentee ballots, regardless of postmark. The law also moved the first day auditors could mail ballots to voters from 29 days to 20 days before the election, increasing the risk that voters would be unable to return their ballots in time.

Bleeding Heartland contacted all 99 county elections offices by phone or email, asking the same set of questions.

1. How many absentee ballots postmarked on or before June 6 arrived too late to be counted?

2. How many ballots rejected because they arrived too late were for the Democratic primary, and how many were for the GOP primary?

3. What was the earliest postmark on a ballot that arrived too late in your county?

A little more than 60 counties either had no late-arriving absentee ballots, or were unable to discern a postmark on any of the ballots that came in after election day. (If the 2019 law had remained in effect, some of those ballots lacking a postmark would have been countable, thanks to the barcode.)

The remaining counties received one or more ballots that were not tallied this year but could have been counted under the old law, because they were postmarked on or before June 6.

At least 149 Iowans (94 attempting to vote in the Republican primary and 55 attempting to vote in the Democratic primary) were disenfranchised for that reason.

The real number of voters harmed by the new deadline is likely higher than what I was able to confirm, because a few auditors declined to retrieve the requested data. Notably, Dallas County Auditor Julia Helm and Scott County Auditor Kerri Tompkins, both Republicans, refused to check the late-arriving ballots for postmarks. So the 149 does not include any of the sixteen ballots in Dallas County or the eleven in Scott County that came in too late to be counted. It’s probable that some of those were postmarked before June 7.

The majority of late-arriving ballots were postmarked June 6. However, dozens had been mailed earlier. The nineteen ballots that couldn’t be counted in Black Hawk County included some postmarked on June 1 or 2 and one postmarked on May 23. Dubuque County had one late-arriving ballot postmarked May 29.

Although Iowa Republicans are less likely to vote by mail than Democrats, they are vulnerable to delivery delays, because mail from rural areas is usually processed in a different county. More than 20 rural counties had between one and five late-arriving GOP absentee ballots. In contrast, Polk County had just one ballot arrive late with a June 6 postmark, and Linn County had none, thanks to sorting centers in Des Moines and Cedar Rapids.

The worst mail delivery problems affected Clinton County.

EXCLUDED BALLOTS COULD HAVE CHANGED OUTCOME OF ONE RACE

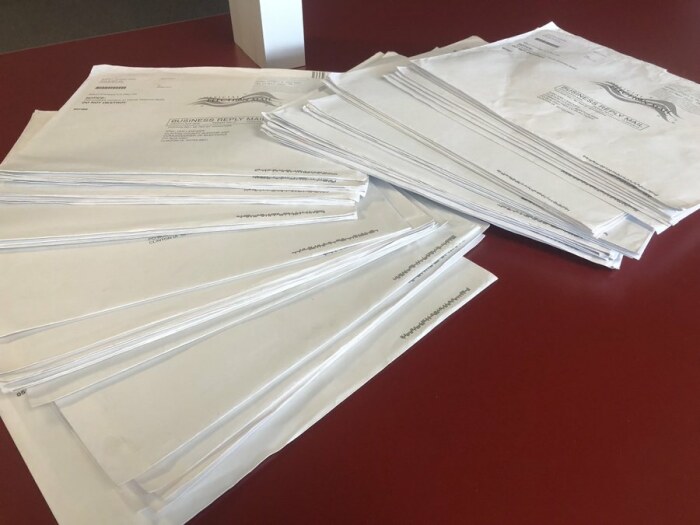

About a quarter of Iowans disenfranchised by the sure count deadline live in Clinton County. According to Auditor Eric Van Lancker, 53 ballots arrived on June 9. Of those, 35 were postmarked on May 27 (eleven days before the primary), one was postmarked June 3, six were postmarked June 4, and eleven had no postmark.

For this post, I’m only counting the 42 with a legible postmark, though Van Lancker noted that some of the eleven might have had a readable barcode if the 2019 law were still operative. He later learned from the U.S. Postal Service that due to a human error at one of the distribution centers, “a tag didn’t get pulled which caused the bin the absentee ballots were in to cycle through the system again, causing the delay in delivery to my office.”

Van Lancker told Bleeding Heartland that the 42 voters who mailed their ballots well before the election, to no avail, included 23 Republicans and nineteen Democrats.

Clinton County had a highly competitive GOP primary for county supervisor, with three contenders for two spots. The third-place candidate, Steve Cundiff, finished just seven votes behind incumbent Dan Srp.

SOME VOTERS DISENFRANCHISED BY HAND-DELIVERY RESTRICTIONS

Iowa’s 2021 law targeted Democratic “ballot chase” operations by making it far more difficult to hand-deliver someone else’s completed absentee ballot to the county elections office. (I am not aware of any criminal case in Iowa related to hand-delivered ballots, so there was no fraud problem that needed to be addressed.)

Under the previous law, voters could ask anyone to take the ballot in: a relative, friend, neighbor, contact from church, Meals on Wheels driver, or a campaign volunteer. But now, unless the voter is blind or physically disabled, the only Iowans who can collect and return a completed ballot are the voter, someone living in the voter’s household, or a family member to the fourth degree of consanguinity.

The new law allows blind or physically disabled voters to designate a “delivery agent” to return their ballot. The delivery agent must be a registered voter and can return at most two ballots per election, and can’t be anyone representing the voter’s employer, union, or a “person acting as an actual or implied agent” for a political party, candidate, or political committee.

Several county auditors told me they were aware of constituents who were unable to return their absentee ballot because they lived alone, did not drive, and had no family nearby to pick up the envelope.

How could they be sure? In some small counties, election workers called voters as the primary approached, to remind them to get their absentee ballot back in. (Larger counties typically don’t have the staff resources to make those calls to every person with a ballot outstanding.)

I heard one such story from Adams County Auditor Rebecca Bissell, a Republican who was critical of the early voting restrictions when the bill was pending in the legislature. She explained in a June 13 email:

We had only one ballot that wasn’t returned. We called the voter to remind them to get the ballot back and he informed us he had broke his leg and couldn’t get the ballot in to us in time for it to be counted. It was too late to mail it to us by the deadline. He didn’t have family that could be the courier and he didn’t know anyone who could bring back his ballot. In addition, he didn’t have a computer to get the form for a non-relative to return his ballot to us in time.

Many Iowans who are physically unable to hand-deliver their own ballots have no internet connection at home, and/or no way to print out a “delivery agent” form.

Expect many more problems along these lines before the general election, when between 1.1 million and 1.3 million Iowans will likely participate, compared to around 352,000 who cast ballots in the June primary.

“Smaller rural counties have a large elderly population who typically choose to vote absentee because of weather or health concerns,” Bissell said at a legislative hearing in February 2021. “Why are we making it harder for them to vote?”

HUNDREDS AFFECTED BY NEW DEADLINE FOR REQUEST FORMS

Not only did the 2021 law make it harder for Iowans to return absentee ballots on time, it made it much harder for voters to request a mailed ballot. Some county auditors had previously budgeted funds and staff time to send request forms to all registered voters in their jurisdictions. The new law prohibits such universal mailings. Auditors can send absentee ballot request forms only to individuals who specifically ask for one.

In addition, voters must now submit an absentee ballot request form to the county auditor by the close of business on the fifteenth day before the election. Iowans used to be able to request a ballot up to the tenth day before most elections.

That five-day shift was impactful. I asked auditors in Iowa’s ten largest counties the following questions:

1. How many voters in your county submitted absentee ballot request forms too late for the June 7 primary, which would have been on time under the previous Iowa law?

2. Of those voters who missed the new deadline for submitting a request form, how many were seeking to vote in the Democratic primary, and how many in the GOP primary?

3. Of those voters, how many in each party ended up casting a ballot in the June 7 primary some other way, and how many did not participate in that election?

Auditors in Polk, Linn, Johnson, Dubuque, Story, Black Hawk, and Woodbury counties were able to answer all of those questions. Across those seven counties, 589 people submitted absentee ballot request forms too late for this year’s primary, but would have been able to receive a ballot under the old law. Those included 337 registered Democrats, 230 Republicans, and some no-party voters (who may change their affiliation to participate in a primary).

Of those 589 Iowans whose absentee ballot request forms arrived too late, 262 managed to vote, either early in person or at a polling place on June 7. Democrats who were able to cast a ballot outnumbered the Republicans who did so, by 172 to 85.

But 327 Iowans (about 55 percent of those who missed the deadline for request forms) ended up not voting in the primary election. More of them were Democrats (167) than Republicans (147). Assuming a return rate of about 90 percent for Iowans who receive an absentee ballot in the mail, some 300 additional voters in these seven counties would have been able to participate, if state lawmakers and the governor had not put new obstacles in their way last year.

Dallas County’s elections office provided no information about late request forms. The Scott County auditor confirmed that 161 of the 173 late-arriving request forms would have been on time prior to 2021, but did not provide a party breakdown or any information about how many of those voters were able to cast a ballot a different way.

Similarly, I learned that 31 of the 36 Pottawattamie County voters who submitted late request forms (mostly Republicans) would have been able to receive an absentee ballot under the previous law. I don’t know how many of those ended up voting in the primary.

In most of the large counties, the early deadline adversely affected more Democrats than Republicans—no surprise, because those counties lean blue, and Iowa Republicans are less likely to choose mail voting. But this problem is not limited to blue counties. The Sioux City Journal’s Jared McNett reported that across northwest Iowa, at least 162 voters submitted absentee ballot request forms too late. His research covered some of the state’s reddest counties, like Sioux, Lyon, and Osceola.

Again, all of these problems will be worse for the general election, which brings out more voters. Seniors will be disproportionately impacted. Woodbury County Auditor Pat Gill told me that of the 29 voters in his county who missed the request form deadline and subsequently did not vote, 23 were at least 60 years old.

Gill added in a June 17 email,

Here in Woodbury County, we were down about 1,500 requests from the 2018 primary which was the last similar election. The voters here were used to getting their ABRs mailed to them because I did it for years. Voters are just now figuring out that they will no longer have them mailed to them. I have fielded many calls from voters who are elderly and disabled that are angry about it, I believe there will many more this fall. I will send letters to all voters explaining the change to them but people do not read their mail.

Gill also said his staff had fielded calls from voters “anxious” about not receiving their ballots. For many years, Iowa county auditors could start mailing absentee ballots 40 days before the election. Republicans shortened the early voting window to 29 days in 2017 and to 20 days last year. Mail delivery often takes longer now as well. Woodbury County mail used to arrive the next day in many cases, but now is sorted in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, adding days to delivery times.

“Voters now have about a week to vote their ballot and drop it back in the mail,” Gill told me. “That may sound like plenty of time but it will take them some time to figure out that they can’t sit on those ballots like they are used to. There was just no valid reason for the legislature to do what they did.”

Story County Auditor Lucy Martin told me, “My own mailed absentee for this election took three days in both directions (Nevada to Ames, Ames to Nevada).” She is concerned about how the new deadlines will affect general election voters. In Story County alone, 145 absentee ballot request forms arrived too late for this primary, and 72 of those voters ended up not participating.

Martin recommends that Iowans wanting to vote by mail in November submit absentee ballot request forms “as soon as possible so that their ballots will go out in the mail on the first day of absentee voting (Wednesday, October 19).” Request forms can be submitted to county auditors offices from August 30 until October 24, which is fifteen days before the 2022 general election.

I now discourage Iowans from voting by mail unless they have no way to vote early in person and can’t make it to a polling place on election day.

SILENCE FROM PROPONENTS OF EARLY VOTING RESTRICTIONS

During the lengthy Iowa House and Senate debates over the 2021 election law, the bill’s Republican architects strenuously objected to accusations of “voter suppression.” State Senator Roby Smith and State Representative Bobby Kaufmann promised that it would still be easy to vote in Iowa.

Kaufmann went so far as to claim the bill “does not suppress a single vote.” He pointed out that some Democratic-controlled states have “sure count” deadlines—but failed to mention that in those states, election officials start mailing ballots much earlier than 20 days before the election, as is the case in Iowa. Since federal law requires ballots to be mailed to overseas and military voters 45 days before the election, there is no benefit to forcing county auditors to wait three and a half more weeks before they can send absentee ballots to other Iowans.

Neither Smith nor Kaufmann responded to Bleeding Heartland’s inquiries about voters disenfranchised in the 2022 primary. How was “election integrity” improved by hundreds of people not being able to participate? What would they say to Iowans who mailed their ballots before this election (in some cases before the end of May), only to have the ballots arrive too late through no fault of their own?

Communications staff for the governor and Secretary of State Paul Pate likewise ignored messages about Iowans who were unable to have their voices heard in the primary. Nor did Pate’s staff explain why the Secretary of State’s office didn’t ask every county auditor to compile the data I was seeking about late-arriving ballots and absentee request forms.

The secretary of state has talked a good game about making Iowa a place where it’s “easy to vote and hard to cheat.” But he apparently doesn’t want to find out how the 2021 law affected Iowans who tried to exercise their fundamental constitutional right. The previous legal standards didn’t facilitate any fraud or cheating.

Top image: Photo posted on social media by Clinton County Auditor Eric Van Lancker, showing dozens of absentee ballots that arrived too late to be counted for the June 7 primary.

1 Comment

Collateral Damage

Pate’s ham-handed attempt to play fast and loose with Iowa voting procedures disenfranchises those voters who’d likely agree with him politically.

dbmarin Fri 1 Jul 10:36 PM