Governor Kim Reynolds made headlines last week with two vetoes: blocking language targeting the attorney general, and rejecting a medical cannabis bill that had strong bipartisan support in both chambers.

A provision she didn’t veto drew little attention. For the foreseeable future, it will prevent Iowa courts from using a tool designed to make the criminal justice system more fair to defendants of all races and income levels.

Reynolds should appreciate the value of the Public Safety Assessment (PSA), since she works closely with two former State Public Defenders: Lieutenant Governor Adam Gregg and the governor’s senior legal counsel Sam Langholz. But last year she ordered a premature end to a pilot program introducing the tool in four counties. The governor’s staff did not reply to repeated inquiries about the reasoning behind Reynolds’ stance on this policy.

Notably, the owner of Iowa’s largest bail bonding company substantially increased his giving to GOP candidates during the last election cycle, donating $10,100 to the governor’s campaign and $28,050 to Republicans serving in the state legislature.

“RICH PEOPLE WHO ARE A DANGER TO SOCIETY CAN PAY THEIR WAY OUT OF JAIL, WHILE POOR PEOPLE WHO POSE NO THREAT TO THE COMMUNITY CANNOT”

Senate File 615, setting the justice systems budget for fiscal year 2020, contained the following passage:

The public safety assessment shall not be utilized in pretrial hearings when determining whether to detain or release a defendant before trial, and the use of the public safety assessment pilot program shall be terminated as of the effective date of this subsection [July 1, 2019], until such time the use of the public safety assessment has been specifically authorized by the general assembly.

The Laura and John Arnold Foundation developed the tool by analyzing data from “750,000 cases from approximately 300 jurisdictions.” Here’s how it works (emphasis added):

- The PSA uses administrative data to produce two risk scores about a defendant: one predicting the likelihood that the individual will commit a new crime if released pending trial, and another predicting the likelihood that they will fail to return for a future court hearing. Scores fall on a scale of one to six, with higher scores indicating a greater level of risk. The PSA also flags defendants that it calculates present an elevated risk of committing a violent crime.

- This objective information can help judges gauge the risk that a defendant poses. However, the PSA does not replace the judge or impede a judge’s discretion or authority in any way.

- The decision about whether to release or detain a defendant always rests with the judge. […]

- Our research has shown that the current pretrial decision making process often results in high-risk defendants being released from jail to await trial, while low-risk defendants are frequently detained. This means that rich people who are a danger to society can pay their way out of jail, while poor people who pose no threat to the community cannot.

- This has negative consequences for individuals, families, and communities, and it disproportionately impacts communities of color and low-income individuals.

- In analyzing the system, we found that judges do not often have access to basic information, such as a defendant’s criminal history, and decisions are frequently made in an entirely subjective manner or with the use of fixed bail schedules.

The nine factors “that most effectively predicted new criminal activity, new violent criminal activity, and failure to appear” were:

- current violent offense

- pending charge at the time of the offense

- prior misdemeanor conviction

- prior felony conviction

- prior violent conviction

- prior failure to appear pretrial in past two years

- prior failure to appear pretrial older than two years

- prior sentence to incarceration

- age at current arrest

The PSA score does not reflect a defendant’s “race, gender, ethnic background, income, substance abuse, mental health, employment status, marital status, or any demographic or personal information other than age.”

“WE HAVE A PROBLEM WITH DISPROPORTIONATE MINORITY CONFINEMENT”

Iowa has long been known for racial imbalance in the criminal justice system, one reason our state has been named among the worst places for African Americans. People of color are treated disparately at every stage of the process: arrests, charging decisions, pretrial detention or bail, and sentencing.

Top judicial branch officials had that problem in mind when they introduced the PSA in some of Iowa’s most populous counties, which also contain the largest number of black or Latino residents. Polk County courts began using the PSA in January 2018. The pilot program expanded to Scott and Woodbury counties (Quad Cities and Sioux City) last March and to Linn County (Cedar Rapids metro area) in July.

Tara Becker-Gray and Thomas Geyer reported for the Quad-City Times in April 2018,

Ultimately, the goal is to prevent defendants who otherwise would be eligible for bond to be held because they don’t have the money to post it, Assistant Scott County Attorney Steve Berger said.

“I think that’s what mostly attracted our (Iowa) Supreme Court to this process,” he said. “They view that it is inherently unfair that people can’t get out of jail simply because they don’t have money,” he said.

“We have a problem with disproportionate minority confinement,” Wayln McCulloh, district director for the 7th Judicial District Department of Correctional Services, said. “We know that persons of a lower socio-economic stratum in society are more likely to be incarcerated.”

A few months into the Scott County experiment, judges there had “followed the recommendation of the PSA 35 percent of the time.”

The pilot project was slated to run through 2019 but ended early, on the governor’s orders. State Representative Gary Worthan, the top Iowa House Republican on the Justice Systems Appropriations subcommittee, added language to a budget bill last year that would have prohibited courts from using the PSA as of July 1, 2018. When Reynolds signed that bill, she item vetoed the relevant section but instructed executive branch agencies to stop participating after December 31, 2018. Judges rely on the Department of Corrections to provide data for each defendant’s PSA score.

“WITHOUT THE ASSESSMENT, A LOT OF THESE FOLKS WILL SIT IN JAIL”

The initial draft of the latest justice systems budget, which the Iowa Senate approved along party lines on April 15, did not address the PSA. Worthan inserted the language as part of his committee amendment the following week. The move was overshadowed by another part of Worthan’s handiwork, which would have reduced the attorney general’s authority to make legal decisions.

When the House debated this bill, Democratic State Representative Marti Anderson offered an amendment to strike the language about the PSA (her remarks begin around 6:44:00 of this video).

This program, this public safety assessment, infuses fairness in our system. And it gives judges the opportunity to use an assessment that’s been tried and tested and can help them decide if the person can be safely released on their own recognizance.

Without the assessment, a lot of these folks will sit in jail, because a judge does not want to take the chance of having someone go out on their own recognizance and harm somebody. I don’t understand why we would ever prohibit the use of an evidentiary-based public safety assessment, by our judges […].

FAUX CONCERNS ABOUT “TRANSPARENCY”

Urging his colleagues to reject Anderson’s amendment, Worthan spoke for less than a minute and raised only vague objections (6:46:35 of the video).

We have folks in our caucus who are concerned with the transparency of the process, and not real comfortable with the assessment as it stands at this point. So until we can resolve those concerns, I’m going to ask that we leave this piece in the bill.

Worthan’s pretext is not credible. The PSA’s nine factors are all related to verifiable facts about the defendant and the case. Without the tool, Iowa judges make more subjective decisions about bail, which is less transparent.

Anderson pointed out in her closing remarks, “These assessments are presented in open court. They are transparent. And they have been tested and are evidentiary.” Nevertheless, House Republicans voted down the amendment along party lines. The following day, the Iowa Senate approved the revised budget bill, again with all Republicans in favor and all Democrats opposed.

By signing this language into law, Reynolds ensured that the PSA cannot be revived in Iowa unless the legislature authorizes its use, which won’t happen under GOP control.

Why wouldn’t Republicans want to make the justice system more fair for defendants who are not wealthy?

FOLLOW THE MONEY

Plans to bring the PSA to Iowa raised alarm bells for Lederman Bail Bonds, which stands to lose business if more defendants are released pending trial without having to post bail. Legislative records show the Midwest’s largest bail bonding company had not retained lobbyists in earlier years but hired a team before the 2018 session to lobby the legislative and executive branches of state government.

High-powered Des Moines attorney Doug Gross made false claims about the PSA in two guest columns for the Des Moines Register, published in November 2017 and January 2018. Gross did not disclose to the Register’s editors or readers that Lederman Bail Bonds had hired some of his law partners as lobbyists.

When Worthan tried to block the PSA in April 2018, he gave the same excuses about “transparency” while admitting to the Des Moines Register that he’d talked to representatives of bail bonding companies. As mentioned above, Reynolds temporarily spared the PSA with her item veto but set an end date for December 31, 2018.

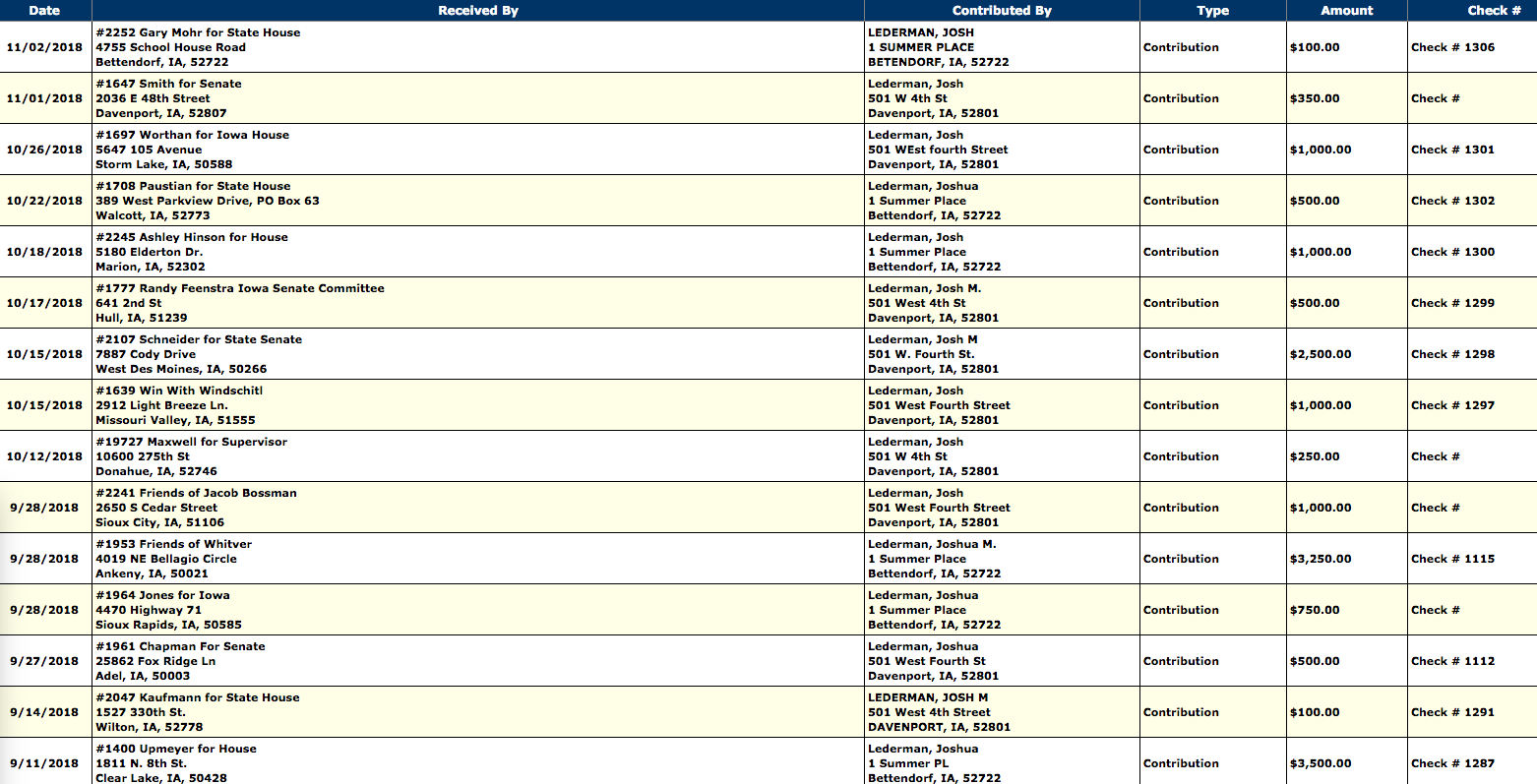

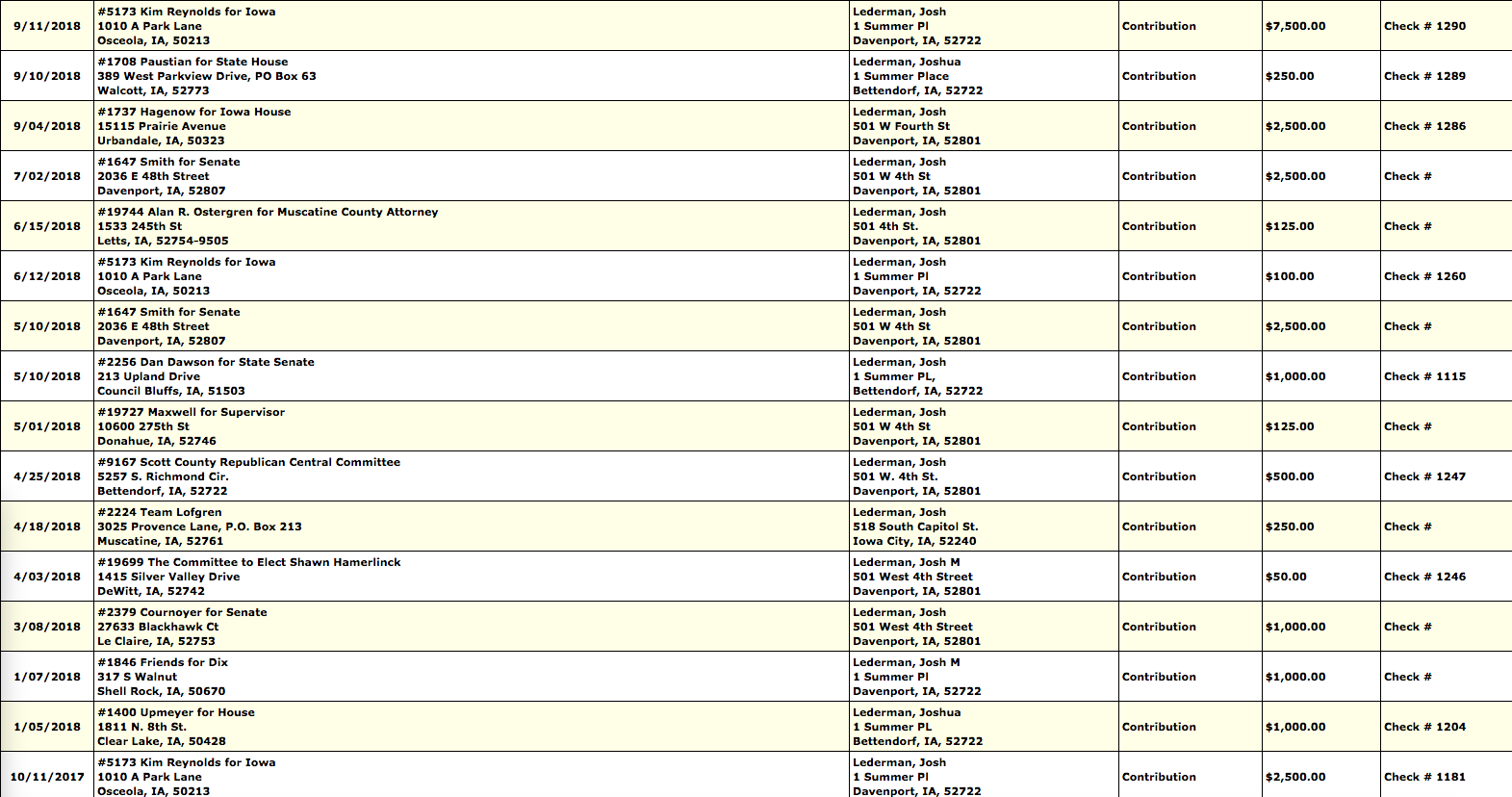

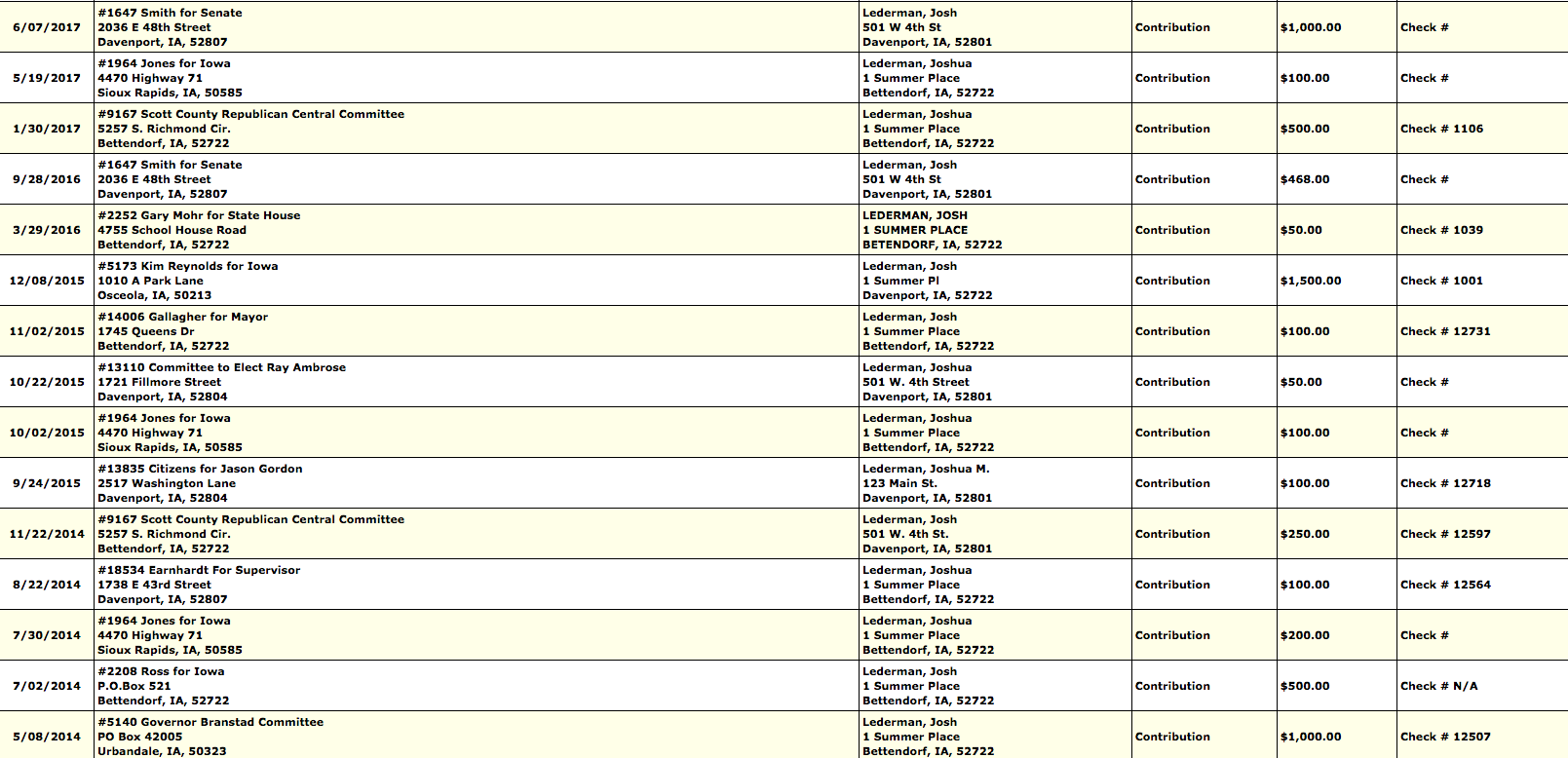

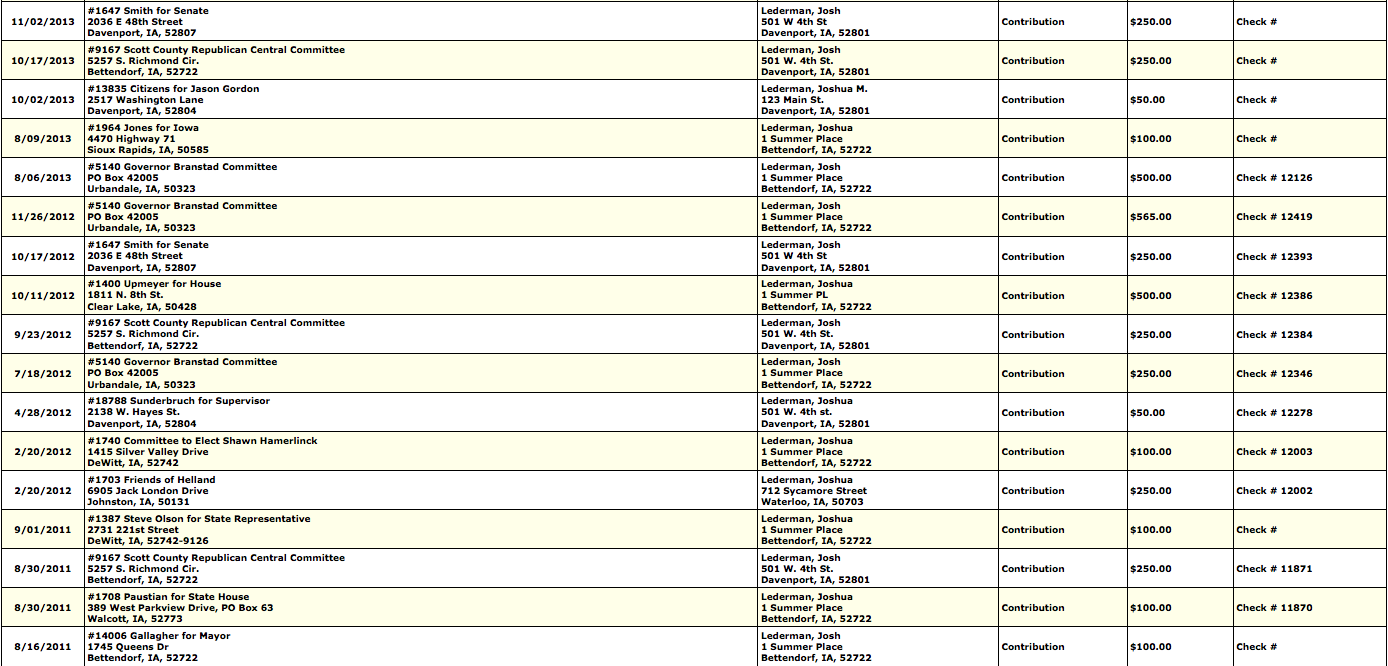

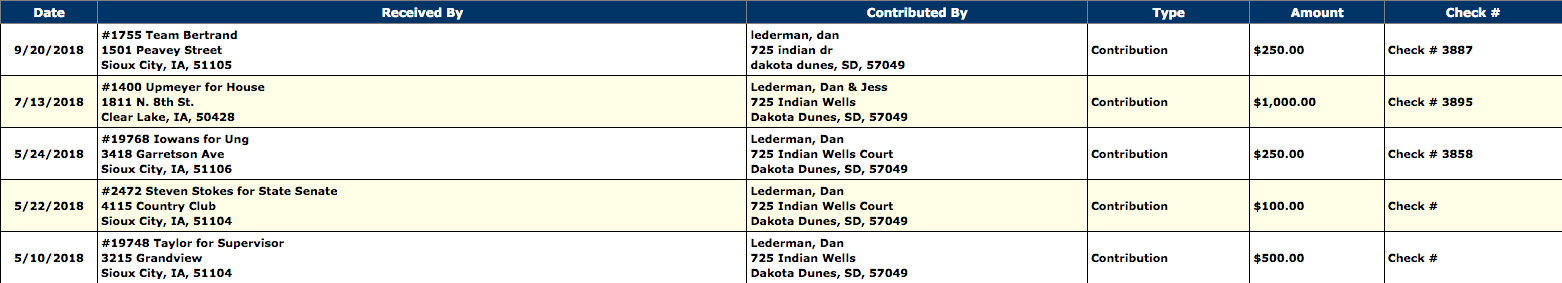

Using the Iowa Ethics and Campaign Disclosure Board’s search engine, I looked up political contributions to state or local candidates by the four Lederman brothers who run the company. The details are enclosed below for those who want to check my math.

The upshot is that Joshua Lederman gave more generously to Reynolds and Republican lawmakers, beginning in late 2017. He had donated $250 to Governor Terry Branstad’s campaign in 2012, $815 in 2013, and $1,000 in 2014, the last time Branstad was on the ballot. Lederman gave Reynolds’ campaign committee $1,500 in 2015 and nothing the following year. Then he donated $2,500 to Reynolds in October 2017, $100 the following June and $7,500 in September 2018, when the governor was in a tight race against Fred Hubbell.

Lederman’s gifts to GOP members of the Iowa House and Senate followed a similar pattern. His donations to Republican lawmakers or statehouse candidates totaled $1,100 in 2012 (four candidates), $350 in 2013 (two candidates), $700 in 2014 (two candidates), $100 in 2015 (one candidate), $518 in 2016 (two candidates), and $1,100 in 2017 (two candidates).

In contrast, last year Lederman spread $28,050 around to the campaigns of nineteen GOP legislators, including four-figure contributions to the top Republicans in each chamber: House Speaker Linda Upmeyer, House Majority Leader Chris Hagenow, Senate Majority Leader Bill Dix, Senate Majority Leader Jack Whitver after Dix’s retirement, and Senate President Charles Schneider. Worthan received $1,000, despite having no Democratic challenger in his House district. Lederman gave to Senator Dan Dawson and Representative Ashley Hinson for the first time; both served on the justice systems budget subcommittee.

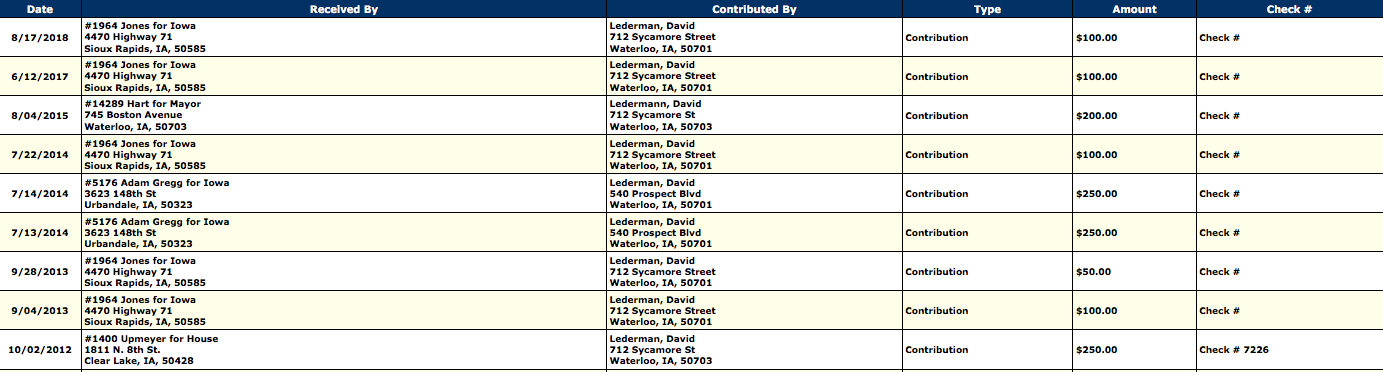

The other brothers involved in the business gave smaller amounts, primarily to legislative candidates in their areas, though Dan Lederman also donated $1,000 to Upmeyer in July 2018.

Lobbyists representing Lederman Bail Bonds donated to some Republican lawmakers or Reynolds last year; for instance, Matt McKinney gave $250 to Hagenow. Since those lobbyists all represented multiple clients, their gifts can’t necessarily be tied to the attempt to gut the PSA.

This episode underscores a major flaw of the Iowa legislature’s reporting system. Lobbyists are supposed to register for or against any bill on which they are actively engaged, and “undecided” when they are watching a bill but haven’t taken a position. Lederman’s lobbyists registered the company undecided on Senate File 615 on April 12. That made sense, because the first draft budget was silent regarding the PSA. The lobbyists should have–but did not–change their registration after Worthan’s committee rewrote the bill to terminate the PSA until “specifically authorized by the general assembly.” That language served no one’s interests but bail bonding companies.

People claiming to care about transparency, as Worthan does, should insist on accurate lobbyist declarations. A change in lobbying on a bill can alert the news media and members of the public that lawmakers altered the content in a significant way.

CUTTING OFF THE PROGRAM MADE SOLID RESEARCH IMPOSSIBLE

Reynolds’ veto message last year said in part,

I disapprove of these sections because I believe that we should consider and study ways to create a fairer pretrial system that protects the public. But I also understand that the legislature and other stakeholders have questions about the PSA and whether it considers all of the appropriate factors. For that reason, I am instructing the agencies of the executive branch to continue their participation in this pilot program until December 31, 2018. At that time, the pilot will be concluded and further use of this assessment suspended until the data from the pilot can be analyzed. If, after studying the data and research conclusions, it is found that this program will be in the best interests of the public, then new legislation should be considered that authorizes the PSA or similar risk-assessment tools.

Sounds reasonable. The trouble is, Reynolds made it impossible for experts to conduct a proper analysis.

The Arnold Foundation had arranged for Harvard Law School’s Access to Justice Lab to study the use of the PSA in Polk and Linn counties, using a randomized trial. Judges would receive PSA scores for half the defendants on their docket and would make pretrial decisions without using the tool for the other half. Data collection was to continue through 2019, after which researchers would track all cases to determine which defendants failed to appear or committed new crimes. Court officials asked for a preliminary report in December. Its findings were predictable.

From the executive summary:

When the PSA and the randomized evaluation launched, the A2J [Access to Justice] Lab warned that, because many criminal cases can take a year or more to reach disposition, and because a sufficient number of cases must reach disposition to allow statistical analysis, credible information on the PSA’s effects would not be available until three to four years after launch. At LJAF’s request, however, the A2J Lab agreed to produce a report by December 3, 2018, discussing the results for the small fraction of randomized cases that had reached resolution by mid-fall of the same year.

As the A2J Lab predicted, credible information about the PSA’s effects in Polk and Linn Counties is not yet available. Too few cases have reached disposition, and those cases that have reached disposition are not representative of the two jurisdictions’ overall arrestee profiles. At this time, based on the small amount of information available, the A2J Lab observes no credible evidence that PSA availability decreases or increases rates of incarceration, failure to appear, new criminal activity, or new violent criminal activity. […]

The A2J Lab’s evaluation design contemplated two years of randomization followed by a two-year follow-up period, the latter included so that cases could reach disposition and to observe post-disposition recidivism rates. The A2J Lab recommends that the evaluation be permitted to finish so that credible information on the PSA’s effects will be available to policy makers who decide whether its use should continue.

Republican lawmakers and Reynolds made sure that won’t happen. In future years, they will have a ready excuse for not authorizing the program: we haven’t seen data supporting it.

Iowa Judicial Branch communications director Steve Davis told Bleeding Heartland on May 28 that “the judicial branch does not plan to ask the legislature to expressly authorize the PSA tool next year.” Did senior court officials conclude the tool has no value? Or do their plans reflect the political reality that GOP lawmakers are not open to this criminal justice reform? Davis replied,

“The use of risk-assessment instruments to determine the likelihood of defendants failing to appear for court or re-offending while on release continues to increase throughout the country. As evidence increases regarding the predictability of these instruments, we hope that will provide more data to policy makers here in Iowa.”

The conservative group Americans for Prosperity advocated for the PSA program to continue. State director Drew Klein told Bleeding Heartland on May 22 that his conversations with the governor’s staff during the legislative session “centered around finding data to help justify extending [the] program. Unfortunately, the Harvard study failed to provide that data.” Klein asked those who had worked with the program for details on financial savings from not incarcerating individuals deemed to present no threat to the public, “but there seemed to be some challenges in pulling that figure together as well.” He added,

“We continue to believe that the PSA is a useful tool as we advocate for reforms across our criminal justice system and will be looking to other states for the data to help us demonstrate its value moving forward.”

Although Reynolds often touts her belief in fair shakes and second chances, she cut short an opportunity to reduce subjectivity and bias in Iowa courts. Keeping low-risk offenders in jail pending trial, solely because they cannot afford bail, is unfair to defendants and expensive for taxpayers.

The demise of the PSA is doubly unfortunate, given that Lieutenant Governor Gregg and Reynolds’ senior legal counsel Langholz should be champions for reducing barriers facing the indigent, having run the State Public Defender’s office.

The only winners in this scenario are the bail bonding companies.

Appendix: Donations from the Lederman brothers to Iowa candidates for statewide, state legislative, or local offices in recent years. (The Iowa Ethics and Campaign Disclosure Board does not track contributions to Iowa candidates for federal offices.) The next four images show gifts from Joshua Lederman.

Gifts from Dan Lederman:

Gifts from David Lederman:

4 Comments

Public Safety Assessment

Thank you, Bleeding Heartland for doing an in-depth story on this issue that got “lost in the frenzy” of the end of session rush to pass budget bills. We should not dictate to the Courts what they can and cannot use to do their job. The failure of this amendment to eliminate bad policy language from a budget bill for on a Party-line vote demonstrates Republicans are not interested in criminal justice reform and fairness. They choose to eliminate a policy that can assure public safety and allow poor people to be released from jail. It costs money to keep people in jail and it costs those people their jobs, freedom, and dignity. The public should be tired of such poor judgment in their representatives to the Iowa Legislature.

martianderson Thu 30 May 5:23 PM

Building a new jail

This assessment is timely in my county where a new jail is being sought by the sheriff. Sometimes we have to send overflow prisoners to other counties for jail space. It’s expensive to bring them back here for every day in court. When asked why these people are in jail before they have been convicted, county supervisors don’t know anything about the bail system.

iowavoter Thu 30 May 9:47 PM

the Polk County jail is also overcrowded

leading to extra costs for taxpayers as defendants are sent to other county jails.

Laura Belin Thu 30 May 11:31 PM

CNN follows your lead--

https://www.cnn.com/videos/us/2019/08/29/bail-bonds-industry-reform-investigation-drew-griffin-lead-vpx.cnn?fbclid=IwAR2khOjsdpV-UaLmfYAbhDIB6k36grR3WLXz0p5PWoPIuG0g_Xyqp1O9PDw

iowavoter Sun 1 Sep 9:58 AM