Gerald Ott of Ankeny was a high school English teacher and for 30 years a school improvement consultant for the Iowa State Education Association.

Before critical race theory (CRT) was named and studied in universities and used to frame legal arguments (and fell into disrepute among Republicans), I learned enough to qualify me as WOKE, at least on a scale with Iowa Governor Kim Reynolds—a low bar, I admit.

It’s a bold claim, one based mainly on the fortuitous experiences of my youth, all before Iowa’s governor was born.

As we know, Reynolds was born and reared in Iowa. She graduated from I-35 High School in 1977, and entered a typical middle-class life of occasional college classes, marriage, children, parenthood, jobs, and local politics beginning in the Clarke County treasurer’s office during the 1990s. She was elected to the Iowa Senate in 2008.

In 2010, the Republican nominee for governor, Terry Branstad, asked her to join him on the ticket. She did; the team won. She completed her college degree at Iowa State University while serving as lieutenant governor.

After Governor Branstad became ambassador to China in 2017, Lt. Governor Reynolds became the 43rd governor of Iowa.

We don’t know what books Reynolds read in high school, but in the 1970s, Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird was the most frequently taught novel. The book frames several themes … empathy and character being two. Did she learn about apartheid in Cry, the Beloved Country a 1948 novel by South African writer Alan Paton?

We don’t know whether she sang about John Brown’s Body or The Battle Hymn in grade school. We don’t know if she studied the Civil War, Lincoln, or the Gettysburg Address. Did she memorize the preamble to the Declaration of Independence? Or to the Constitution?

Whatever she read, watched, or studied, she has never claimed her own public high school education or college classes were tainted with malicious indoctrination by abusive teachers trying to imprint a liberal bias or pornographic images in her head.

Nor has she claimed her own daughters were subject to indoctrination or liberal influence by their public school teachers.

Nor does she say she complained to local school officials about texts, materials, songs, lessons, or library books that may have encouraged her daughters to judge others based on race, gender or sexual identity, rather than by the content of their character.

So, it’s no exaggeration to say matters of race, gender, or sexual identity, or labels or unhealthy stereotypes, or wickedly liberal indoctrination had little opportunity to enter or corrupt Reynolds’ brain in her early life, at least up until she read the “how-to” manual for red-state governors.

Reynolds must have studied the manual pretty well, because by 2021 she felt sufficiently schooled on race, inequality, and other allegedly divisive concepts to offer and sign legislation, which (she claimed) targets the teaching of critical race theory and other concepts in government diversity trainings and classroom curriculum. It’s like an oath red-state governors must take.

When she signed the new law, the Des Moines Register quoted her as saying, “Critical Race Theory is about labels and stereotypes, not education. It teaches kids that we should judge others based on race, gender or sexual identity, rather than the content of someone’s character. I am proud to have worked with the legislature to promote learning, not discriminatory indoctrination.“

Her words are not original. The flawed analogy is standard fare in right-wing speeches. The line is a misappropriation of a few words from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s famous speech, given in summer of 1963 at the Lincoln Monument in the nation’s Capitol. He famously calls for freedom to ring from every mountaintop.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day down in Alabama, with its vicious racists, . . . one day right there in Alabama little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers. I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight, and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. “I Have A Dream” Speech (in part), August 28, 1963. From Teaching American History. (accessed July 23, 2023).

King’s speech is great American literature, as finely crafted as the Declaration of Independence, the Preamble to the Constitution, or Lincoln’s Address at Gettysburg after a great battle in 1863 where 50,000 men were killed, maimed, or captured, testing whether the nation would split in two with African-Americans continuing to be enslaved or hold together with African-Americans becoming free citizens.

Today, politicians in some parts of the U.S. are again aiming to define what constitutes history, and to shape what teachers are allowed to present.

Florida governor Ron DeSantis’ intervention into the teaching of Black history dates at least to summer 2021. That June, the state Board of Education banned “critical race theory,” a catchall term used on the right to denote various teachings about race, and the New York Times’s 1619 Project from classrooms. DeSantis spoke to the board before its meeting, telling the members that “some of this stuff is, I think, really toxic” and that “we will not let them bring nonsense ideology into Florida’s schools.”

The campaign has since shifted to state lawmakers. Between 2021 and 2023, the Republican-dominated legislature — with DeSantis’s guidance and encouragement — adopted a raft of laws restricting teaching about sex, gender, race and racism. One such measure that took effect in July 2022, known as the “Stop WOKE Act,” prohibits teaching that an individual, by virtue of his or her race or color, “bears responsibility for … actions committed in the past by other members of the same race.” Signing this law in April 2022, DeSantis promised: “We are not gonna use your tax dollars to teach our kids to hate this country or to hate each other.”

“All the ways Ron DeSantis is trying to rewrite Black history : From laws to standards, Florida’s governor is shaping and limiting what students can learn,” By Hannah Natanson in Washington Post, July 24, 2023

If a democracy depends on youngsters carrying forward the lessons of the past, public schools and educators can not be satisfied with ignorance.

It’s hard not to see that result in findings by the Southern Poverty Law Center in a late 2016 online survey of 1,000 U.S. high school seniors. Fewer than one in 10 identified slavery as the central cause of the Civil War – even though South Carolina, the first to leave the Union, explicitly cited protecting slavery as the reason in its secession declaration.

All We Are is Memory by Donna Bryson, In this special edition, host Kim Vinnell follows two Reuters journalists on their personal journeys to confront family connections with slavery and racial violence. Plus, the investigation into more than 100 lawmakers with slaveholding ancestors. A must read.

School children must sing the songs of freedom, recite the poems, and learn and practice the fine arts of a democracy—at the ballot box and in all public and private life. Denying a kid’s right to be fully educated is treasonous and detaches a youngster from the essence of being an American.

Did you, too, O friend, suppose democracy was only for elections, for politics, and for a party name? I say democracy is only of use there that it may pass on and come to its flower and fruit in manners, in the highest forms of interaction between people, and their beliefs – in religion, literature, colleges and schools- democracy in all public and private life.

Walt Whitman 1819-1892

Becoming Woke to America

I want to be clear, my education did not qualify me as an expert in any academic or collegiate understanding of race, inequality, and other, quote, “divisive concepts.” Merely as an emerging WOKEster.

I did take a class in Civil War history at Grand View University just as the pandemic started, so our class retreated into ZOOM. Thanks to the lectures and readings Professor Kevin Gannon provided, I learned a bunch (became, so to speak, a bit “woke”) about the Civil War, Reconstruction, and the laws, history, and personalities of those grueling times. (Dr. Gannon is now Professor of History at Queens University of Charlotte.) So yes, Virginia, studying American history will make your brain grow.

Is it CRT or racism or both?

At an Iowa legislative committee meeting in February 2021, State Representative Bobby Kaufmann took offense saying he was not a “racist” because he had been the floor manager for new, more restrictive voter laws.

He criticized a document available to Ames teachers on the district’s website. He said “it’s garbage” and “inaccurate” to teach kids that there are racist motivations behind some voting restrictions.

“By having crap like this—the very equity that you’re trying to achieve—there’s being created a new inequity.”

Kaufmann’s logic escapes me, but his complaint raises the question: Can a man or woman who plans, writes, and passes a law designed to discriminate based on race not be considered racist?

CRT does not attribute racism to white people as individuals or even to entire groups of people. Simply put, critical race theory states that U.S. social institutions (e.g., the criminal justice system, education system, labor market, housing market, and healthcare system) are laced with racism embedded in laws, regulations, rules, and procedures that lead to differential outcomes by race. Sociologists and other scholars have long noted that racism can exist without racists.

However, many Americans are not able to separate their individual identity as an American from the social institutions that govern us—these people perceive themselves as the system. Consequently, they interpret calling social institutions racist as calling them racist personally. It speaks to how normative racial ideology is to American identity that some people just cannot separate the two. There are also people who may recognize America’s racist past but have bought into the false narrative that the U.S. is now an equitable democracy. They are simply unwilling to remove the blind spot obscuring the fact that America is still not great for everyone.

Why are states banning critical race theory? Rashawn Ray, Alexandra Gibbons, The Brookings Institution. November 2021

Black Codes were racism embedded in laws. In November 1865, following the Civil War, the government that President Andrew Johnson had set up in Mississippi passed a set of oppressive laws that only applied to African Americans known as the Black Codes. Other Southern states quickly followed suit. The intent of these laws was to restrict African Americans’ freedom, and compel them to work for white employers in a situation reminiscent of slavery.

KIDADA WILLIAMS: The basic purpose of the Black Codes was to recognize that slavery has been abolished, but to make sure that there is as little change from slavery to freedom as possible.

ERIC FONER: The key to the Black Codes was what they call vagrancy laws, things like that. Every adult black person was required to sign a labor contract for the year with a white employer. If they didn’t do that they would be considered a vagrant and they could be fined. And if they couldn’t pay the fine they could be auctioned off to someone who would pay the fine, and then they’d have to work off the fine for that person.

PBS: Reconstruction: America After the Civil War

Mine Eyes Have Seen the Coming of the Lord

My dad was an Air Force chaplain. When he left the service, he took a church in Mound City, Kansas. Mound City is located in Linn County next to Missouri’s western border about eighty miles straight south of Kansas City. I started fifth grade there in 1953.

Right off my dad joined the town’s American Legion. He became friends with a Black man, also an airman who had flown missions during WWII. Dad hired him to paint our house. I helped, so we got acquainted and became friends. His name, curiously, was Billy Graham. I asked him if he was named after the famous television preacher. “No, I’m older,” he said, “he ‘as named after me.” I got the joke, and we both laughed.

Billy would have known the meaning of “woke” as it began appearing in the 1940s. It was first used by African Americans to “literally mean becoming woken up or sensitised to issues of justice,” as per linguist and lexicographer Tony Thorne. But in 2014, as per VOX, following the police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, “stay woke” suddenly became the cautionary watchword of Black Lives Matter activists on the streets, used in a chilling and specific context: keeping watch for police brutality and unjust police tactics.

In the years since Michael Brown’s death, “woke” has evolved into a single-word summation of leftist political ideology, centered on social justice politics and critical race theory. This framing of “woke” is bipartisan: It’s used as a shorthand for political progressiveness by the left, and as a denigration of leftist culture by the right.

Baptist preachers got “fifth” Sundays off to take vacations or supply elsewhere. On one fifth Sunday, Billy Graham asked my dad to speak at his African church in the segregated part of town where he lived. My mother and I went along. The music was loud and happy.

Afterward, a deacon in our church came to our door and cautioned my dad against speaking there again. “We keep them separate here,” he told Dad at the door where we gathered. When Dad understood what the deacon wanted, he stepped outside to continue their conversation, which I didn’t hear. That didn’t stop me from scooting across the highway to visit Billy pretty often.

In fifth grade, our class learned and sang a song about John Brown whose “body lies a-moldering in the grave/ But his soul goes marching on.” We learned several verses, including the one about him freeing slaves: “John Brown died that the slaves might be free / John Brown died that the slaves might be free / His soul goes marching on.”

We didn’t learn the backstory or much of the context of the song. Vaguely, I understood John Brown stuck up for enslaved “Negroes,” as our teacher said. She told us Black (she said “colored”) Union soldiers marched to the song during the Civil War, a piece of American history still pretty vague to us fifth graders.

We learned the John Brown song for a school performance as part of the town’s centennial celebration. The melody, first stanza and chorus have stuck with me since.

As I said, our music teacher Mrs. Carr didn’t tell us much about John Brown or what he had done. I think she thought we already knew about him because there was a street in town named John Brown Drive.

At the centennial concert, when we fifth graders finished our John Brown song, Mrs. Carr pointed to the junior high students who rolled into the Battle Hymn of the Republic, another Civil War song.

Of all the songs written during the Civil War, the Battle Hymn has been a fixture in patriotic programs for over 160 years and is still sung in schools and churches across the nation, but more so in the North. With its many biblical allusions, in particular the line, “In the beauty of the lilies Christ was born across the sea,” I always assumed the Battle Hymn was a church song. But …

In the “Battle Hymn,” there is no separation of church and state. The United States is a divine vessel propelled on the rough seas by the breath of God. Indeed, the nation’s wars have often been imbued with providential fire. Americans on both sides of the Civil War came to see the struggle as a holy war, with Christ and his armies arrayed against the Beast. One Pennsylvanian soldier wrote: “every day I have a more religious feeling, that this war is a crusade for the good of mankind.”

The Atlantic Magazine

As far back as I can remember, high school music students in Iowa have preformed the Battle Hymn at the Annual All-State Music Festival, a production shown statewide on public television and featuring the state’s elite student musicians. No doubt Governor Reynolds has attended a concert.

The song’s lyrics ask “us” (the Civil War-era masses who heard the song) to be willing to die to free the slaves, a big ask in 1861. As sung by 21st century All-State students, the call might be a summons to “live for”social justice i.e. “to make men free,” which (arguably) slips into the gray area of instruction banned by Iowa’s new state laws outlawing critical race theory.

I hope the history and context of both songs are parts of the kids’ instruction at the Music Festival.

The poet and abolitionist Julia Ward Howe joined a party inspecting the condition of Union troops near Washington D.C. in 1861. To overcome the tedium of the carriage ride back to the city, Howe and her colleagues sang army songs, including “John Brown’s Body.”

One member of the party, Reverend James Clarke, liked the melody but found the lyrics to be distinctly un-elevated. The published version ran “We’ll hang old Jeff Davis from a sour apple tree,” but the marching men sometimes preferred, “We’ll feed Jeff Davis sour apples ’til he gets the diarhee.” Might the poet, Howe, the Reverend wondered, craft something more fitting?

The next day, Howe awoke to the gray light of early morning. As she lay in bed, lines of poetry formed themselves in her mind. When the last verse was arranged, she rose and scribbled down the words with an old stump of a pen while barely looking at the paper. She fell back asleep, feeling that “something of importance had happened to me.”

The editor of the Atlantic Monthly (at the time), James T. Fields, paid Howe five dollars to publish the poem, and gave it a title: “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

You can listen here to a 1908 recording of the song from “The Edison Phonograph Monthly,” featuring “Miss Stevenson, Mr. Stanley and Mixed Quartette.”

The Atlantic Magazine

John Brown

In seventh grade, we studied Kansas history and learned about “Bleeding Kansas.” We had a filmstrip about the Kansas-Nebraska Act and Kansas’s own civil war (circa 1854-1860) over whether the then-territory would enter the U.S. Union as a slave or free state. In that era, Mound City and the county thereabouts were centers of anti-slavery militia. PBS has gathered a unit of teaching resources.

According to PBS, John Brown was born into a deeply religious family in Torrington, Connecticut, in 1800. Led by a father who was vehemently opposed to slavery, the family moved to northern Ohio when John was five, to a district that would become known for its antislavery views.

During his first fifty years, Brown moved about the country, settling in Ohio, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and New York, and taking along his ever-growing family. (He would father twenty children.)

Working at various times as a farmer, wool merchant, tanner, and land speculator, he never was finacially successful — he even filed for bankruptcy when in his forties. He also participated in the Underground Railroad and, in 1851, helped establish the League of Gileadites, an organization that worked to protect escaped slaves from slave catchers. (PBS)

John Brown

Despite his contributions to the antislavery cause, Brown did not emerge as a figure of major significance until 1855 after he followed five of his sons to the Kansas territory.

There, he became the leader of antislavery guerrillas and fought against a proslavery attack on the antislavery town of Lawrence. The following year, in retribution for another attack, Brown went to a proslavery town and brutally killed five of its settlers. (See below.) Brown and his sons would continue to fight in the territory and in Missouri for the rest of the year. (PBS)

At the age of 55, John Brown moved with his sons to Kansas Territory. In response to pro-slavery raiders sacking of (free-state) Lawrence, Kansas, John Brown led a small band of men to Pottawatomie Creek on May 24, 1856. The men dragged five unarmed men and boys, believed to be slavery proponents, from their homes and brutally murdered them.

American Battlefield Trust

We learned the real John Brown had camped in the Mound City area prior to a raid into Missouri to free slaves. Our teacher said Brown had been a local hero in Linn County, then a Free State stronghold.

According to history posted on the Mound City town website: “While in Linn County, John Brown (AKA “Shubel Morgan”) usually made his headquarters at a Mr. Agustus Wattle’s house (an old stone house two miles north of Mound City) with a few men on whom he could depend. Wattle’s house, or its remnants, was still visible in the 1950s. Our seventh grade teacher took several of us kids to see the site and what was left behind. A real historic site, it was eerie to be where John Brown had once been.

On the 20th of December (1858), Brown’s men in two parties, one under his own command, and the other under command of J. K. Kagi, went into Missouri to liberate slaves. Brown’s party liberated ten slaves and returned. Kagi’s party liberated one slave and killed the owner, a German who could neither understand nor speak English.”

Mound City — City Website

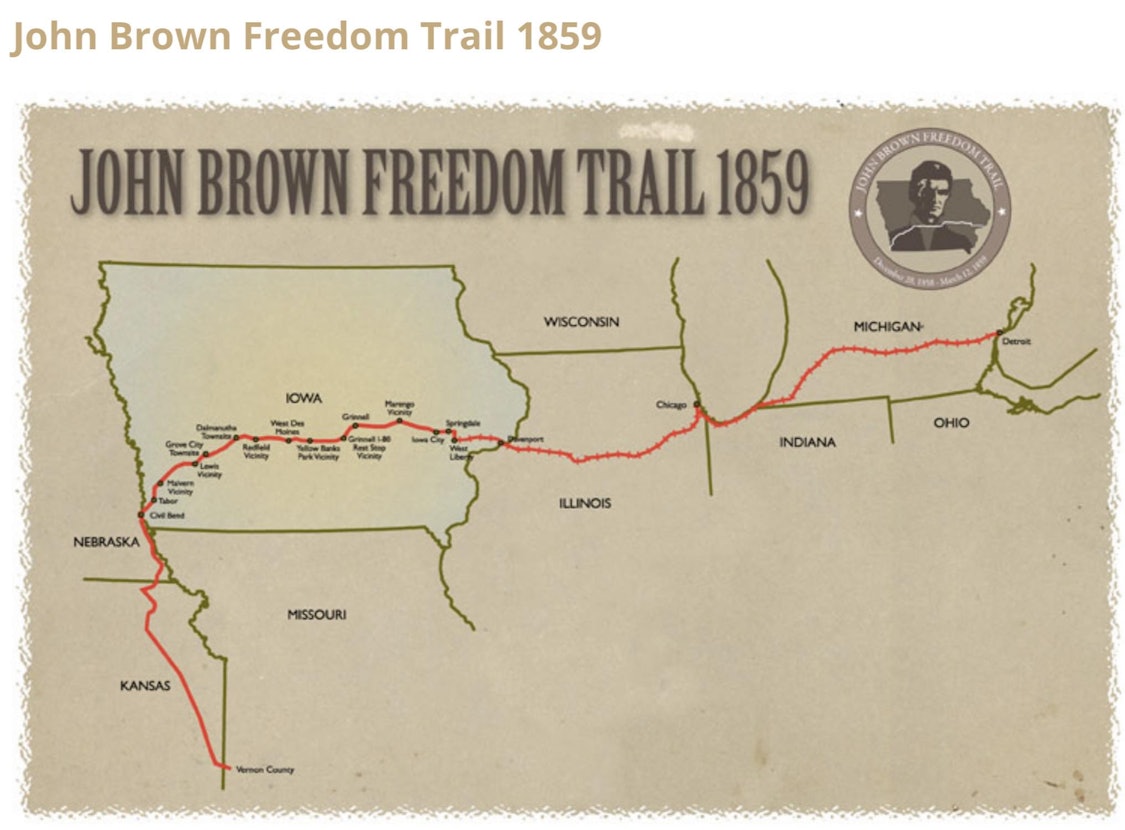

We learned Brown had escorted the dozen or so slaves to freedom in Canada, using the Underground Railroad that passed through Iowa and Illinois.

As per the Iowa Department of Cultural Affairs, after conducting a raid into Missouri on December 20, 1858, John Brown, with twelve men, women, and children freed from slavery, plus ten of his own men (including three Iowans), crossed into Iowa on February 4, 1859 to begin a fateful final journey across Iowa during February and March.

Antislavery and underground railroad participants who operated north-of-the-border states knew Iowa as their westernmost free-state link. The risks of this already dangerous activity of helping escapees increased on September 18, 1850 when the United States Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, that required all law enforcement to aid in the recovery of runaway slaves and prosecution of traffickers.

Brown was no stranger to the territory, having traveled in Iowa many times before. [Editor’s note: Daniel G. Clark has written for Bleeding Heartland about some of Brown’s travels, including his final visit to Iowa in 1859, and efforts by local historians to mark the Iowa Freedom Trail.]

This time was different, with some Iowa residents taking a dim view of Brown’s recent exploits (Pottawatomie Creek). In spite of this, supportive sympathizers aided the party as it proceeded.

Our teacher went more into the story, telling that Brown had led a raiding party of abolitionists to Virginia to try to start a slave revolt by taking over a U.S. armory at at place called Harpers Ferry. Several were killed. [Editor’s note: Iowan Edwin Coppoc was among those executed for participating in the raid on Harpers Ferry.]

The Good Lord Bird

For actor Ethan Hawke (as per the New York Times), disavowing white supremacy was the defining ideology of John Brown. Hawke played the white abolitionist in Showtime’s 2020 series “The Good Lord Bird.”

According to Times writer Salamishah Tillet, a professor of African-American and African studies and creative writing at Rutgers University, the actor Hawke spent his early years in Texas “hearing Brown was a nut.”

“He was a white man who went to war against white people to help free slaves. He wasn’t nonviolent. White people call John Brown a nut … any white man who is ready and willing to shed blood for your freedom — in the sight of other whites, he’s nuts. As long as he wants to come up with some nonviolent action, they go for that, if he’s liberal, a nonviolent liberal, a love-everybody liberal. But when it comes time for making the same kind of contribution for your and my freedom that was necessary for them to make for their own freedom, they back out of the situation.”

Malcolm X Quotes in Goodreads

Actor Ethan Hawke said Brown was the most challenging, rewarding and politically urgent character he had played in his 35-year acting career. His seven-part film is part satire, part historical fiction, based on the 2013 National Book Award novel of the same name, written by the Black writer James McBride.

I found “The Good Lord Bird” to be a rough and tumble rendition that jerks at a viewer’s emotions. In today’s hysteria over race-related instruction, recommending the film to high school history students would, at minimum, stir notice. Of course, kids can watch the movie on television.

Brown’s life ended on the gallows in 1859 in Harper’s Ferry VA (now WVA) after an attempt to rally a slave insurrection by violently attacking a federal arsenal in the town.

Certainly, a disturbing image for a kid, one that left me, in junior high, wondering if Brown was a hero for his plan to free slaves — or a traitor for attacking a federal armory and killing people. Full story of Brown’s execution. Brown’s speech at his arraignment for attacking the armory has become a quotable piece of American literature.

I have, may it please the court, a few words to say. In the first place, I deny everything but what I have all along admitted — the design on my part to free the slaves. I intended certainly to have made a clean thing of that matter, as I did last winter when I went into Missouri and there took slaves without the snapping of a gun on either side, moved them through the country, and finally left them in Canada. I designed to have done the same thing again on a larger scale. That was all I intended. I never did intend murder, or treason, or the destruction of property, or to excite or incite slaves to rebellion, or to make insurrection.

This was (first paragraph) of John Brown’s last speech during his trial by by the Commonwealth of Virginia in Charles Town, Virginia (now part of West Virginia). Brown was executed December 2, 1859. An interesting fact of history is that, the evening before Brown was executed, a group of soldiers slept in the courtroom. One of them was John Wilkes Booth. Brown was, of course, executed for seizing the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry in October, 1859, for the purpose of arming slaves for an insurrection. In The National Center for Public Policy Research.

Aftermath

The impact of Harpers Ferry quite literally transformed the nation,” says Harvard historian John Stauffer, author of The Black Hearts of Men: Radical Abolitionists and the Transformation of Race. The tide of anger that flowed from Harpers Ferry traumatized Americans of all persuasions, terrorizing Southerners with the fear of massive slave rebellions, and radicalizing countless Northerners, who had hoped that violent confrontation over slavery could be indefinitely postponed. (Excerpt)

Before Harpers Ferry, leading politicians believed that the widening division between North and South would eventually yield to compromise.

After it, the chasm appeared unbridgeable. Harpers Ferry splintered the Democratic Party, scrambled the leadership of the Republicans and produced the conditions that enabled Republican Abraham Lincoln to defeat two Democrats and a third-party candidate in the presidential election of 1860.

“Had John Brown’s raid not occurred, it is very possible that the 1860 election would have been a regular two-party contest between antislavery Republicans and pro-slavery Democrats,” says City University of New York historian David Reynolds, author of John Brown: Abolitionist. “The Democrats would probably have won, since Lincoln received just 40 percent of the popular vote, around one million votes less than his three opponents.” (Excerpt)

While the Democrats split over slavery, Republican candidates such as William Seward were tarnished by their association with abolitionists; Lincoln, at the time, was regarded as one of his party’s more conservative options.

“John Brown was, in effect, a hammer that shattered Lincoln’s opponents into fragments,” says Reynolds. “Because Brown helped to disrupt the party system, Lincoln was carried to victory, which in turn led 11 states to secede from the Union. This in turn led to the Civil War.”

Harvard historian John Stauffer and City University of New York historian David Reynolds. Quoted in Smithsonian Magazine, October 2009 in article by contributor Fergus M. Bordewich.