“If you didn’t know anything about this process, and I told you how it was set up, you would think that a right-wing Republican set this process up, because it really makes it harder to vote than it should be,” Julián Castro told a room full of Iowa Democrats at Drake University on December 10.

Castro’s campaign organized the town hall (which I moderated) to highlight problems with the Iowa caucus system and a calendar that starts with two overwhelmingly white states.

Now that Castro has ended his presidential bid, it may be tempting to dismiss his critique as sour grapes from a candidate who wasn’t gaining traction in Iowa.

That would be a mistake. Castro is only the most high-profile messenger for a sentiment that is widespread and growing in Democratic circles nationally.

If Iowa Democrats want to keep our prized position for the next presidential cycle and beyond, we need to acknowledge legitimate concerns about the caucuses and take bigger steps to make the process more accessible.

CASTRO’S CASE AGAINST THE CAUCUSES

For the extended version of Castro’s views on Iowa’s role, you can watch the video from his town hall at Drake or read the full transcript, which Eric Appleman transcribed and published at Democracy in Action.

Castro’s argument boils down to three points:

1. Iowa and New Hampshire are demographically not representative of the country or the Democratic Party.

2. Caucuses are inherently flawed because of the many barriers to participation and the lack of a secret ballot.

3. The country and party have changed a lot in the five decades since a Democratic task force approved a calendar putting Iowa and New Hampshire first.

DENIAL AND DEFLECTION WON’T CUT IT ANYMORE

For years, influential Iowa Democrats rarely acknowledged any problems with how we manage our first-in-the-nation responsibility. Asked about an emergency room worker who couldn’t get the night off to attend the 2008 caucuses, then state party chair Scott Brennan told a New York Times reporter, “there’s always the next cycle.”

Since I started writing about exclusionary or unrepresentative features of the Iowa caucus system in 2007, I’ve often been told the caucuses are “not an election,” but a neighborhood meeting geared toward party-building. (As if the chance to weigh in on the next presidential nominee isn’t the only reason 99 percent of caucus-goers choose to spend a winter evening in a crowded room.)

When the unusually close result in 2016 sparked demands for a recount and frustration that no one could say for sure whether more Iowans showed up for Hillary Clinton or Bernie Sanders, party leaders reflexively defended our “quirky” and “unique” process. They implied that people who wanted to know how many Iowans stood in each candidate’s corner didn’t understand that caucuses “don’t always lend themselves to clear results.”

Members of the Iowa caucus review committee formed in the spring of 2016 rejected calls to release raw numbers for each candidate in addition to the delegate count. The party will release a head count next month, but only because of new Democratic National Committee requirements for caucus states.

Even now, one occasionally hears Iowans invested in the status quo make a virtue out of the caucus system’s obvious flaws. The Des Moines Register’s business model relies on caucus coverage. The newspaper’s longtime political columnist Kathie Obradovich wrote in September,

caucuses are not intended to be convenient. In fact, caucuses should be inconvenient. The entire process works the way it does because it forces voters to give up most of an evening in the middle of winter. Voters who are willing to make that much of a sacrifice for participation are also going to be willing to educate themselves about the issues and the candidates. Many of them are going to be willing to donate money or time to help get that candidate elected.

Helping to select the next president shouldn’t be an endurance test. And anyone who has worked or volunteered for a presidential campaign can vouch for the fact that many Iowans are well-informed and deeply invested in a candidate, but unable to attend the their precinct caucus for various reasons.

ACCEPTING WHAT WE CANNOT CHANGE

Castro has argued that it’s hard to reconcile the Democratic Party’s longstanding reliance on black voters with starting the presidential race “in two states that hardly have any African Americans at all.” He got some pushback during the town hall from Iowans who noted that people of color do live here. They include around 120,000 African Americans and some 200,000 Latinos.

I don’t mean to erase the experience of any group, but the latest available data indicate whites not identifying as Latino comprise about 85 percent of Iowa’s population. While some of our communities have a lot of diversity, as a state we do not reflect the demographics of the U.S. or the Democratic Party in particular.

When Iowa’s whiteness comes up in this context, the most common rebuttal one hears is that Iowans propelled Barack Obama to the 2008 nomination. Castro responded at the town hall,

one exception does not prove the rule on anything. […] And the idea is not that it can never happen, it’s that it’s a lot harder, it makes it more difficult, because the diversity that’s represented in a lot of other parts of the country is not represented here.

As many commentators have observed, Pete Buttigieg has polled better in Iowa than Castro or Cory Booker, both of whom were mayors of larger cities than South Bend, have extensive federal government experience, and more advanced degrees. Race is likely not the only relevant factor, but who thinks whiteness has nothing to do with it?

Some defenders of Iowa’s status question the impact of race, given that Joe Biden leads the polls in South Carolina, which has a much larger percentage of African-American voters. Castro has responded that starting in more representative states is not mainly about helping candidates who are not white. It’s about giving people of color a chance “to elect their first choice candidate,” whoever that may be. As things stand now, voters in more diverse states “have less people to choose from,” because candidates doing poorly in Iowa and New Hampshire typically drop out.

A Drake University undergraduate (and person of color) returned to this point when asking the final town hall question. Current polling doesn’t suggest that starting in a “state that’s more diverse, makes much of a difference.” Castro’s answer was powerful.

Watch this exchange. pic.twitter.com/QpEIiYBj8X

— Sawyer Hackett (@SawyerHackett) December 12, 2019

From Eric Appleman’s transcript:

Well, I mean, I take your argument, but I think that if we accept that argument, which is basically that the diversity of the state doesn’t make a difference, does the diversity of a company make a difference? Does the diversity of university make a difference? Does the diversity of a newspaper or media outlet make a difference? To say that it doesn’t make any difference in this context, I believe is basically to say that no company, university, no media outlet, television and film, also shouldn’t have a responsibility to evaluate the diversity of their enterprises. If we’re not even going to make the effort to ensure that our democracy itself reflects our country’s diversity and our party’s diversity, why should the private sector do that? And, you know, I don’t know if any one candidate in this election would be doing better if another state were going first. But I do believe that overall, and in the long term, absolutely you would have different outcomes if different states went first and second versus tenth or fifteenth.

Residents of Iowa and New Hampshire can’t magically make our states more diverse. Our whiteness shouldn’t automatically disqualify us from going first and second. But it does mean that when the DNC revisits the calendar after November 2020, the burden will be on us to show why we deserve to keep our early spots. We must do everything we can to make our nominating contests as representative as they can be in other ways.

That will require an attitude adjustment in both states.

ACCEPTING THAT BARRIERS ARE REAL

How hard is it to attend a caucus? Consider the 2016 turnout in Iowa and Connecticut, states with similar-sized electorates. Dozens of candidate visits, massive amounts of media coverage, and the combined efforts of hundreds of campaign staffers here helped bring about 171,000 Democrats to their precinct caucuses.

In contrast, more than 322,000 Democrats cast ballots in the closed Connecticut primary, which took place after 36 other states had voted, when Clinton had more or less locked up the nomination. Clinton visited that state once before the primary, while Sanders did not campaign there.

Also worth noting: the non-binding 2016 primaries in Nebraska and Washington attracted far more voters than did the more important caucuses those states held earlier in the year. About 33,460 Nebraska Democrats attended their caucuses, but more than 80,000 cast ballots for Clinton or Sanders in the meaningless primary two months later. The disparity was even greater in Washington: turnout reached 230,000 for the caucuses in March and about 800,000 for the “beauty contest” primary in May.

CHANGING WHAT WE CAN

Iowa can’t switch to a primary without amending state law. Even if we tried, New Hampshire law says that state must hold the first primary. We’re stuck with a caucus if we don’t want to vote for president in June. But we could do more to help Iowans take part in the caucuses.

Castro has often remarked that our nominating system hasn’t changed since 1972. It’s not for lack of trying! Since the early 1980s, Democratic leaders in Iowa and New Hampshire have worked together against efforts by other states to jump ahead.

That cooperation produced an unfortunate side effect. For a generation, our party leaders have made placating New Hampshire Secretary of State Bill Gardner a higher priority than giving thousands of disenfranchised Iowans a voice in choosing the president.

I can’t count the number of times I’ve suggested to Democratic insiders that we should hold a straw poll caucus like Iowa Republicans do, or provide some absentee or early voting option for those who can’t attend in person. Invariably, I’ve been told we could never do that, because Gardner would think it’s too much like a primary. Top Democrats have said the same thing out loud on many occasions.

The Iowa Democratic Party’s original plan to offer a “virtual caucus” by phone in February 2020 appeared to be designed to suit Gardner, who objects to anything resembling a ballot here. When the DNC nixed the phone-in caucus for security reasons, Iowa pursued an expanded satellite caucus program.

The satellite caucuses are a welcome addition. I would have appreciated the opportunity to participate when I was living abroad. But let’s not kid ourselves. The 99 approved locations for February 3 (click here for the full list) should accommodate several hundred people, perhaps a few thousand. It’s not going to expand participation by even 5 or 10 percent.

People who don’t drive, or can’t leave their homes at night due to a disability or caregiver responsibilities, won’t have access to any satellite caucus. Neither will most shift workers and snowbirds. Tens of thousands of people in those groups might have had access to a virtual caucus. An Iowa poll by Selzer & Co for the Des Moines Register last February found that a phone-in option could have expanded participation in the Democratic caucuses “by nearly a third.”

Another group disenfranchised by the current system are those who prefer to keep their political preferences private. After the demise of the virtual caucus, Castro released a statement calling the DNC’s action “an affront to the principles of our democracy.” I asked him about that during the town hall. He explained,

You need to in the least, the Iowa caucuses needs to open up the ability of people to participate at different times, and essentially to have an early voting component to it. And not make people show up in one place at one time, and by the way, without a secret ballot, right, there’s no secret ballot.

That means that let’s say that you’re an employee, and you show up and your supervisor’s there at the same caucus, or the owner of your business, if you work for a small business. And, you know, how do you feel if that person is passionate about a candidate, and they’re saying, hey, come over here with me, you know.

He added that he’d hoped the virtual caucus would clear a path for people in “mixed status families” to participate. In the Latino and Asian-American community, a lot of people have one or more undocumented immigrants in their household. They may fear drawing public attention to their families. “And so the more that you can provide the intimacy of a secret ballot and their ability to participate that way, the more likely they’re going to be to show up during this Trump era, especially. The virtual caucus would have been a little bit better than the traditional caucus at that.”

On a related note, I’ve heard of small business owners who choose not to caucus because they don’t want to alienate customers by publicly supporting a candidate.

WHAT NEEDS TO HAPPEN AFTER 2020

Although Iowans may see Castro as a sore loser, he didn’t offer any new ideas about our beloved tradition. People from around the country have long complained about the lack of diversity in Iowa and New Hampshire. As a precinct captain in 2003, years before I thought I’d ever be writing about Iowa politics, I was troubled to realize how many highly engaged voters would not or could not attend their caucus.

Ideally, Democratic leaders in the early states would have gotten ahead of the curve. But the prevailing attitude here seemed to be, maintain a united front with New Hampshire and all will be well. No one was going to displace Iowa while President Obama was in office.

The Iowa Democratic Party introduced the satellite caucus concept last cycle, but the result was “mere tokenism”: four locations serving a total of 119 people (109 of them at one senior living facility).

Anger is growing among Democratic activists nationwide. Talented candidates of color have left the presidential race or failed to qualify for televised debates, while a white candidate with a thinner resume is in Iowa’s top tier.

Saving the caucuses may be a lost cause, if this year’s winner in Iowa doesn’t win the nomination, or if the general election candidate loses to Donald Trump.

Assuming there is a chance to keep our place in line, Iowa leaders need to press forcefully for making the caucuses inclusive: an early voting period and some kind of absentee ballot. New Hampshire leaders need to get over their hang-up about not allowing any whiff of a primary here. We’re going to sink or swim together. Iowa needs to be able to show that going forward, every eligible and interested voter will be able to register a preference for a presidential candidate.

We can preserve some elements of the neighborhood meeting for party-building (adopting platform resolutions, electing county committee members and convention delegates). Let everyone who only cares about the presidential race vote from home, or state a preference and then go home.

This change would have the collateral benefit of solving what John Deeth has called the “fundamental problem” of recent caucuses in Iowa’s larger counties: “enough rooms that are big enough simply do not exist.”

Castro will advocate for a new DNC task force to examine the calendar for the 2024 primaries.

People from different backgrounds, different experiences and they should get together and create a system of rank ordering these states. Some of the things that I believe should go into that are, how reflective the state is of the diversity of the party and the country, the size of the state and how easy or expensive it is to campaign in that state. Also, if we say that our values are that we want to make it easier for people to vote, how easy do those states make it for people to vote? Is there early voting? Is there vote by mail, you know, how many voting locations do they usually have in most of their, their areas? We can come up with a, a thoughtful, effective way to rank order the states, and then you also give an incentive to actually get better about how accessible they make voting to people.

Iowans can make a lot of points in our favor:

Whether a DNC task force would find those arguments more compelling than the case for starting in states with more diverse populations, I can’t say.

But I am sure our long run will end if Iowa Democrats don’t commit to correcting some of the caucus system’s real shortcomings before we go to the negotiating table.

“THIS IS ABOUT WHETHER WE’RE GOING TO LIVE BY OUR VALUES”

Iowans have a lot riding on remaining first to pick a president. At Castro’s town hall in Des Moines, Black Hawk County Democrats chair Vikki Brown (who is African American) warned that “if it wasn’t for the caucuses, we would be a deep red state, just like Nebraska. And I’m not looking forward to that.”

Many experienced hands believe organizing by presidential campaigns before the 1984 caucuses was crucial to Tom Harkin’s victory over an incumbent Republican U.S. senator that November.

Contenders and those with ambitions to run someday support down-ballot candidates and local party organizations through donations, headlining events, and sometimes assigning staff to help with GOTV. Last year, organizers for various presidential campaigns knocked doors for Democrats running for the state legislature, city council, or school board.

Besides the tangible benefits for the party, Iowa caucus-goers are fortunate to have the opportunity to see presidential candidates up close. For many (including me), the precinct caucus itself is fun and exciting.

I don’t want 2020 to be the last gasp of the Iowa caucuses as we know them. That’s one reason I feel so strongly that Democrats need to set aside feelings of defensiveness and accept Castro’s challenge “to take a look at our own house.”

Most of us won’t agree with how he proposes to change the calendar, but that shouldn’t stop us from improving our system. As Castro told the Drake town hall audience, “This is about whether we’re going to live by our values as Democrats who encourage more voting instead of limiting that voting.”

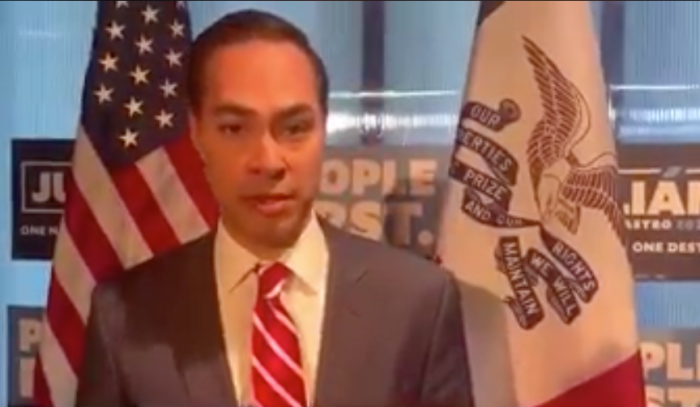

Top image: Screen shot from a video Julián Castro recorded immediately after his town hall meeting in Des Moines on December 10, 2019.

6 Comments

Some reactions

“small business owners who choose not to caucus because they don’t want to alienate customers by publicly supporting a candidate.”—I hear this all the time about why small towns can’t populate even their own school boards. But a small town attorney who ran unsuccessfully for state house last cycle told me his ostentatious politics had no impact on his law practice one way or the other. So is there any evidence for some of the objections to caucuses?

The main reason the diverse field did not catch on either in IA or in national polls is that most of them are unknown names to the general public. The names who are most widely known have topped the polls all along until Buttigieg flashed in the pan.

There’s also the theory that minority voters are convinced by the anti-Obama reaction that another minority can’t win at this time. So starting in Iowa hardly makes a difference.

The people who can’t attend the caucus may feel personally shunned but they cannot claim broader participation might change the result. A caucus of a hundred Iowa voters would be too small, of course, but these caucuses attract many thousands of voters. Increasing participation by many thousands more would not produce a different result.

Tom Harkin said years ago that Iowa remains first because no one has a better idea. That’s still true. We should not tell Iowans that we will lose our roll if we fail to select the next President on Feb 3. (That in itself seems pretty anti-democratic with respect to all the other states) That warning prompts people to abandon the candidate they prefer and migrate to the candidate the press tells them will be most likely to win. Y’ know, like Hillary in 2016, or Kerry in 2004.

I’d like to hear about proxy voting as a way to expand participation. But I’m not sure the cure for imperfect democracy is always more democracy, so I’m skeptical it would quiet the jealous critics if we made changes. They are jealous–that is most of the story.

iowavoter Fri 3 Jan 10:08 PM

I don't think we can say for sure

that increasing participation by many thousands would not produce a different result.

The experiences of Nebraska and Washington in 2016 suggest the opposite. Bernie won both of those states’ caucuses easily, but Hillary won the primaries by a wide margin. If caucuses are much harder to attend for senior citizens, lower-income people, shift workers etc., there may be candidates who would do a lot better in a primary with higher turnout.

I believe Joe Biden will be hurt far more than Warren, Sanders, or Buttigieg by the demise of the virtual caucus, because his strongest bloc is older voters.

Laura Belin Sat 4 Jan 9:21 AM

My estimate

of the Democratic Primary vote is:

57% White

20% African American

15% Hispanic

6% Asian

The point that Iowa is ideological representative is a good one.

Dan Guild Sat 4 Jan 7:24 AM

this is across all primaries and caucuses?

Interesting.

Laura Belin Sat 4 Jan 9:21 AM

this is what the focus should be

Since we aren’t pretending to represent the whole state, we should focus more on OUR demographics, as a party, being first in the nation. I’d be interested to see sources–or see the IDP take on this sort of research–shouldn’t be awfully hard to do. i don’t think we should necessarily be first, but if we intend to stay first (and who doesn’t like having all the opportunities to meet candidates 100 times if you really want to) — but if not us, then who–where all those benefits exist for those not funded like the man who thinks he should skip the caucus and buy his way into the race later.

marytnurse Mon 6 Jan 11:55 AM

Making the Iowa Caucuses What They Are Not II

There is a time-tested method to gain disproportionate national press attention by a presidential candidate whose Iowa caucus campaign is on the ropes. To create an impression of uncommon political bravery, that candidate need only make a series of frontal assaults on the Iowa caucuses themselves.

The media, ever mindful of its residual obligation to give attention to “all sides” of every debated issue, feels duty-bound to balance all of the nice things that most of the vote-seeking candidates say about Iowa and its voters while they comb through the state’s 99 counties looking for support. The media achieves its illusion-of-balance by focusing attention on lone dissenting voices who spend their limited resources attacking the caucus system, itself, rather than campaigning in more traditional fashions.

Not since 1988, perhaps, when Al Gore, finding his fledgling campaign to be sinking in the dust of Iowa’s hustings, secured headlines by attacking the caucus system, has any Democratic candidate for president gained such attention by launching an Iowa-Caucus-Attack as has Julian Castros, most recently. Had Castros gotten as much press attention earlier-on, while promoting his candidacy for president on its own merits, the outcome of his campaign efforts might have been different, and better.

Whatever may ail the Democratic Party’s nomination system, it would be odd of the Iowa caucus system–the same system, the same people, who, in very recent years, has elevated the candidacies of persons irrespective of race (Barack Obama) or gender (Hillary Clinton)–were to be disproportionately blamed for its short-comings.

A presidential nomination system, for example, that, as in this cycle, invites no less than 24 candidacies into its process is bound to be confronted by unexpected, adverse consequences. Not the least of these consequences are the very real possibilities that serious issue discussions will be precluded and that a candidate’s celebrity status, most importantly, will determine the nomination process outcomes more than political experience or issue positions–no matter where (Iowa or otherwise) that nomination process begins or ends. If we remain a party that equates sound democratic (small “d”) nomination processes with 24 candidates-on-a-stage, we cannot claim to be surprised when–as did Donald J Trump three years ago after debating large stages of Republican Party candidates–a celebrity ambushes the party entirely. What if, after all, Ophrah Winfrey had decided to run for president? Think things would be looking differently for the other candidates competing in the Iowa caucuses right about now? No doubt Michael Bloomberg is onto something when he skips the Iowa caucuses and the early, smaller states in the nomination process altogether in anticipation of meeting a large field of candidates down-the-road, in states where media budgets promoting celebrities make all the difference.

Not often discussed in the criticisms and defenses of the Iowa caucus system are the original animating principles that were no less important back in 1972, when Iowa’s populist giant, Harold E Hughes, proposed fundamental nomination process reforms, that included caucus options, than they are today.

First, while Iowa need not necessarily always be first in the nomination process, it is also the case that Iowa provides a remarkably level playing field for any such process to begin. With 3 million people dispersed amongst 99 counties and approximately 950 cities, there are no political machines here. Coalitions created by activists to elect one person to one office one campaign year dissipate immediately after the election, to be re-created in some new way, by a different mix of persons and groups, to elect the next person to another office the very next election. Anyone seeking the Democratic party’s presidential nomination in any election cycle in Iowa must start from scratch. Such a situation does not characterize many states. Iowa’s uniqueness in this respect is a strength, not a weakness. Getting Iowa off the earliest stages of the nomination process will not likely improve the outcome at the end of the line.

Second, Iowa’s relatively small population, spread out over as many as seven media markets makes investments in media-driven campaigns problematic, if not economically-challenged. A campaign with limited resources can do as well–or better–than well-healed media-centered approaches, assuring that candidates must test-drive their messages in front of real people before they are catapulted into the more populated media-saturated larger states, places where large-budgeted celebrity candidates have built-in advantages, after the Iowa caucus experience concludes.

Third, a major–perhaps the most important, and deeply undervalued by the Gore-Castros critiques–virtue of the Iowa caucuses is that such meetings allow an opportunity for real people to get together in real places with real neighbors for a boisterous good time (a few hours of more authentic excitement than even Netflix movies can deliver its subscribers), no ringers, no known fraud, and, in the end, produce, sometimes brutally, very credible evidence to the rest of the nation as to which of the fledgling candidacies should likely not go forward.

Some of the caucus reform proposals–whether wittingly or not–would appear to be fashioned to turn the Iowa Democratic Party’s caucuses into some other version, although more deeply flawed, of the old-school Iowa Republican Straw Poll. Other proposals–the electronic satellite caucuses come to mind–would appear, at best, to deny the accountability that face-to-face in-person caucuses assure or, at worst, to invite the infiltration of non-resident operatives. To what end? At what, if any, gain?

The Iowa caucuses–one important part of Hughes’s post 1968-convention reforms designed to break the unit rule method of nominating presidential candidates, to reduce the dominating influence of power-brokers and to democratize the nomination processes, generally–were never intended to create a perfect system. Rather, as a small, yet important, early step of the nomination process, it is hard to imagine significantly improved system under which the Iowa Caucuses were to be significantly altered or eliminated, as most recently proposed by a disappointed Julian Castros on his way out the door.

JamesCLarew Sat 4 Jan 2:13 PM