Bruce Morrison is a working artist and photographer living with his wife Georgeann in rural southeast O’Brien County, Iowa. Bruce works from his studio/gallery – a renovated late 1920s brooding house/sheep barn. You can follow Morrison on his artist blog, Prairie Hill Farm Studio, or visit his website at Morrison’s studio.

When we found the acreage here in southeast O’Brien County 20 years ago, it was the perfect fit for us. We had a few trees and a small bit of wooded habitat with nice spring ephemerals, and some great hillside gravel slopes with actual native prairie remnants, something that has become less easy to find in Iowa.

This little spot may not be on the super quality charts, but even places like ours are disappearing much too frequently. The photographs shown here depict a little piece of what once was, when prairie habitats covered most of what is now Iowa.

We first found ten species of native grasses in the pastures here…types like Prairie Muhly, Western Wheat Grass, Scribner’s Panic Grass, June Grass, and more common types. This gave us hope we would eventually find at least “some” native forbs (prairie wildflowers).

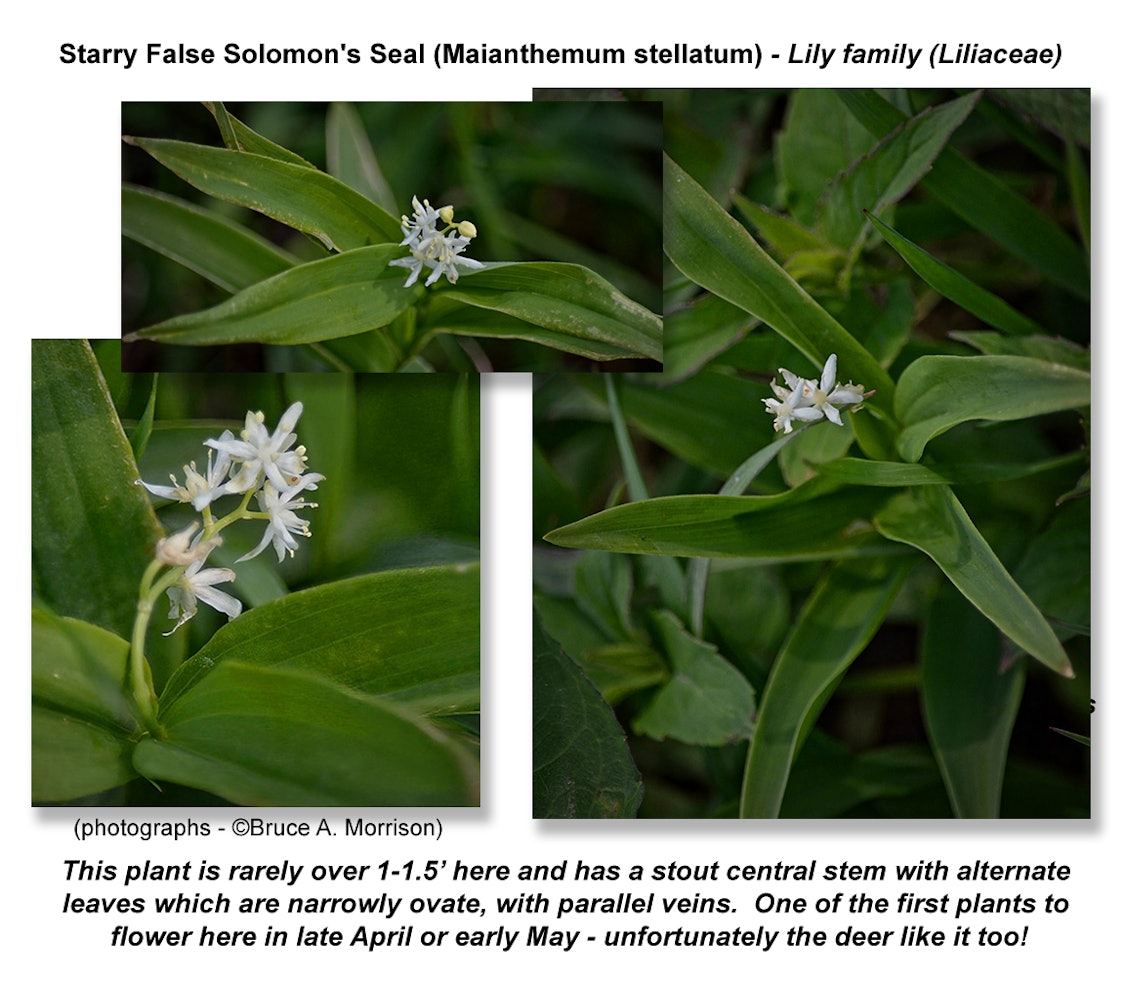

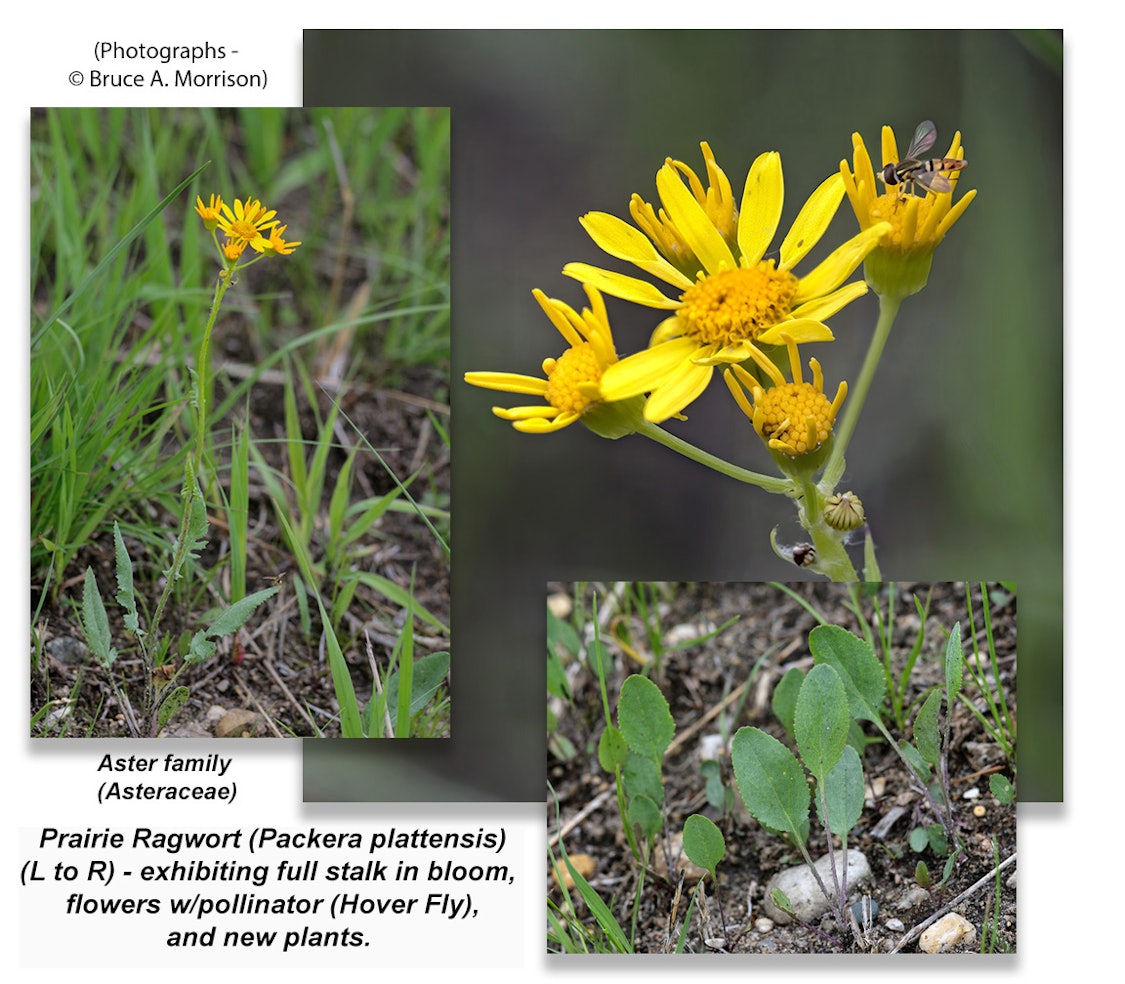

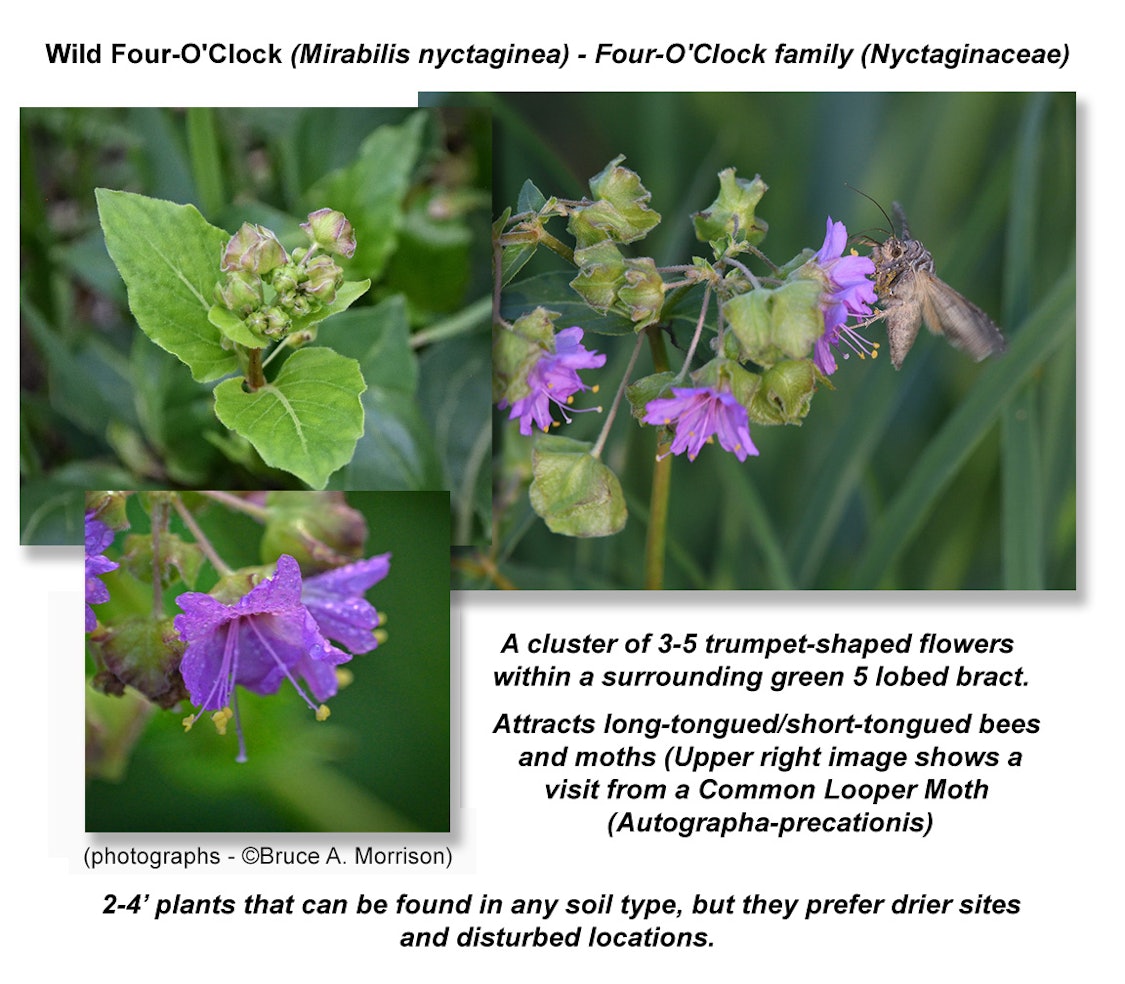

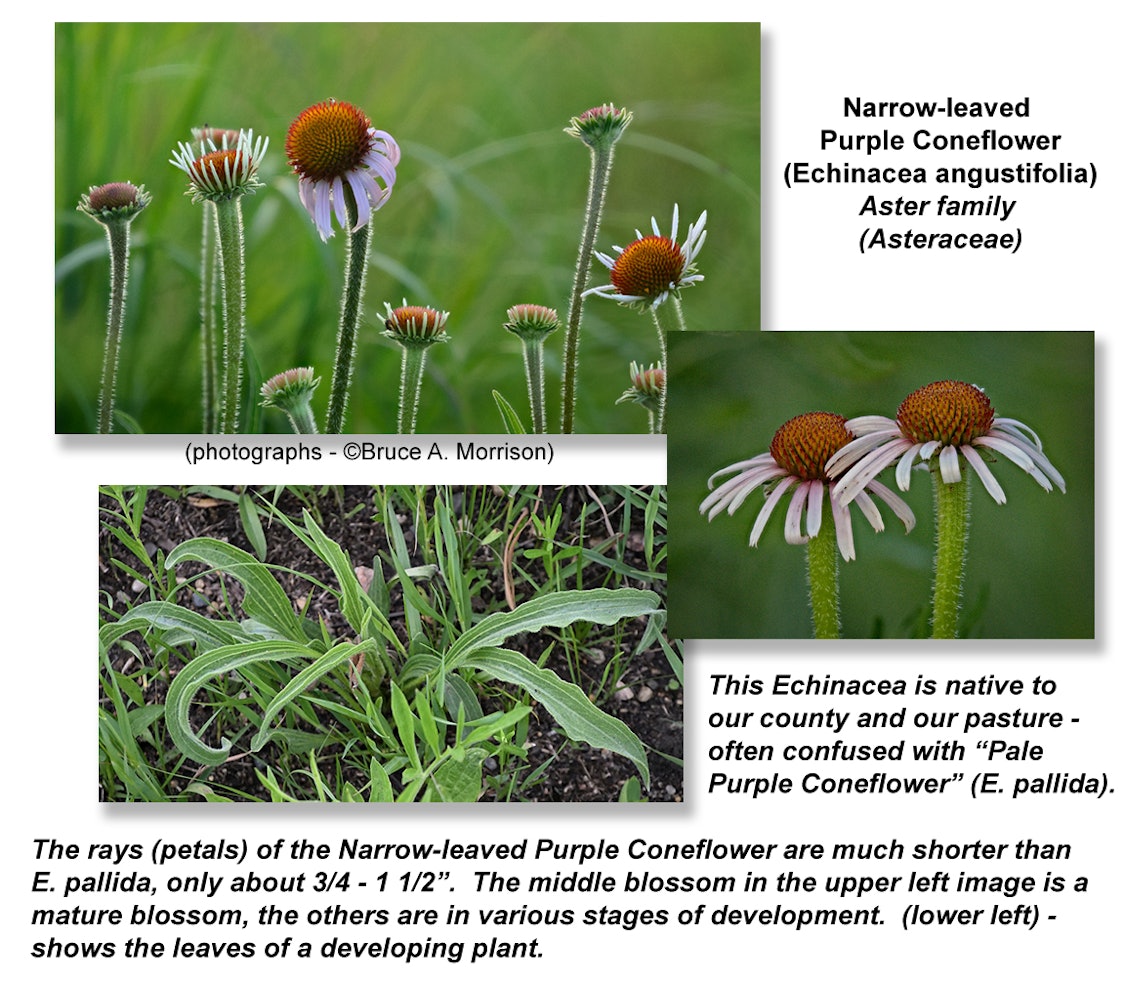

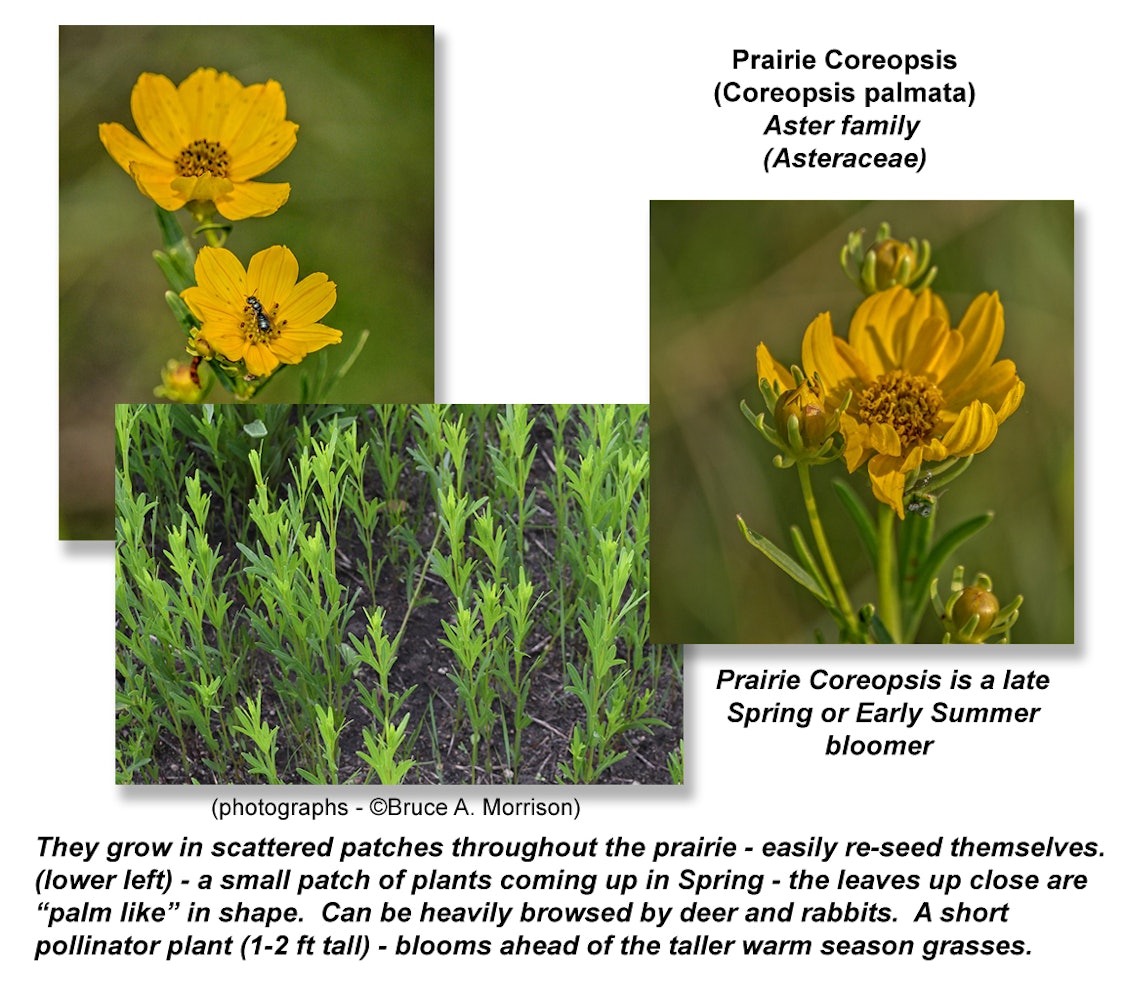

We did a burn late that first Fall. The first year we noticed a few of the most common forbs like Starry False Solomon Seal, Canada Anemone, Blue-eyed Grass, Prairie Ragwort, Gray-headed Coneflower, Wild Four O’clock, Obedient Plant, Stiff Goldenrod, and others.

Through the years we have made many more discoveries—some isolated to a specific location, others becoming widespread as we managed for natives.

Each spring here begins with great anticipation. It has been a long winter in the art studio, painting away the days and dreaming of the prairie!

It is hard to describe that wonderful feeling of finally being out in the pastures, getting much needed exercise after being cooped up inside so long. Hearing the birds and the many other critters day and night is such a tonic.

Late last fall we burned the north pasture west side hill and picked seed from the northeast and east pasture hillsides and bottom ground. I prefer planting in the fall; the seed has a natural period to lay and then germinate once the spring arrives. But it doesn’t always work the way you want.

The ideal fall planting is to broadcast just before a snow event, and so I did last December. We had a snow event forecast for the 15th, so I worked into the dark the night before, broadcasting seed on the freshly burned ground. I looked forward to the snow blanketing everything until spring thaw. Yea, right.

We had our first ever winter derecho on December 15, 2021, bringing 75 mph+ winds and snow (but mostly wind). Apparently the hillside burned and freshly seeded pasture was completely blown clean. Not a flake of snow remained, and I could not find evidence of the seeding whatsoever. Well, best laid plans and all that, as they say.

Much of this particular area had been part of a grove, which the former owners had cut down and planted to brome. We’ll try again next year.

The spring was late here in the northwest corner of the state. Very dry and cooler than normal, so plants were about two weeks behind.

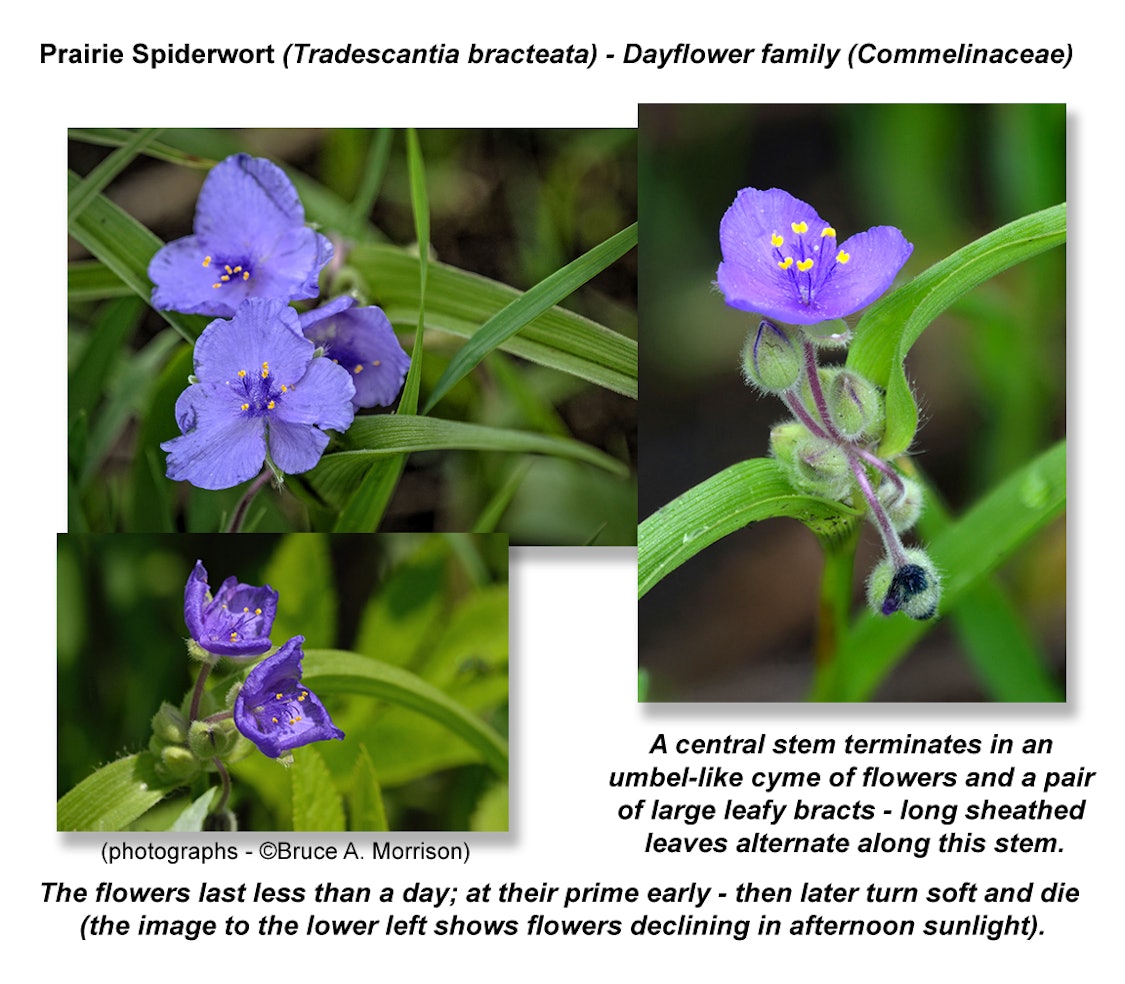

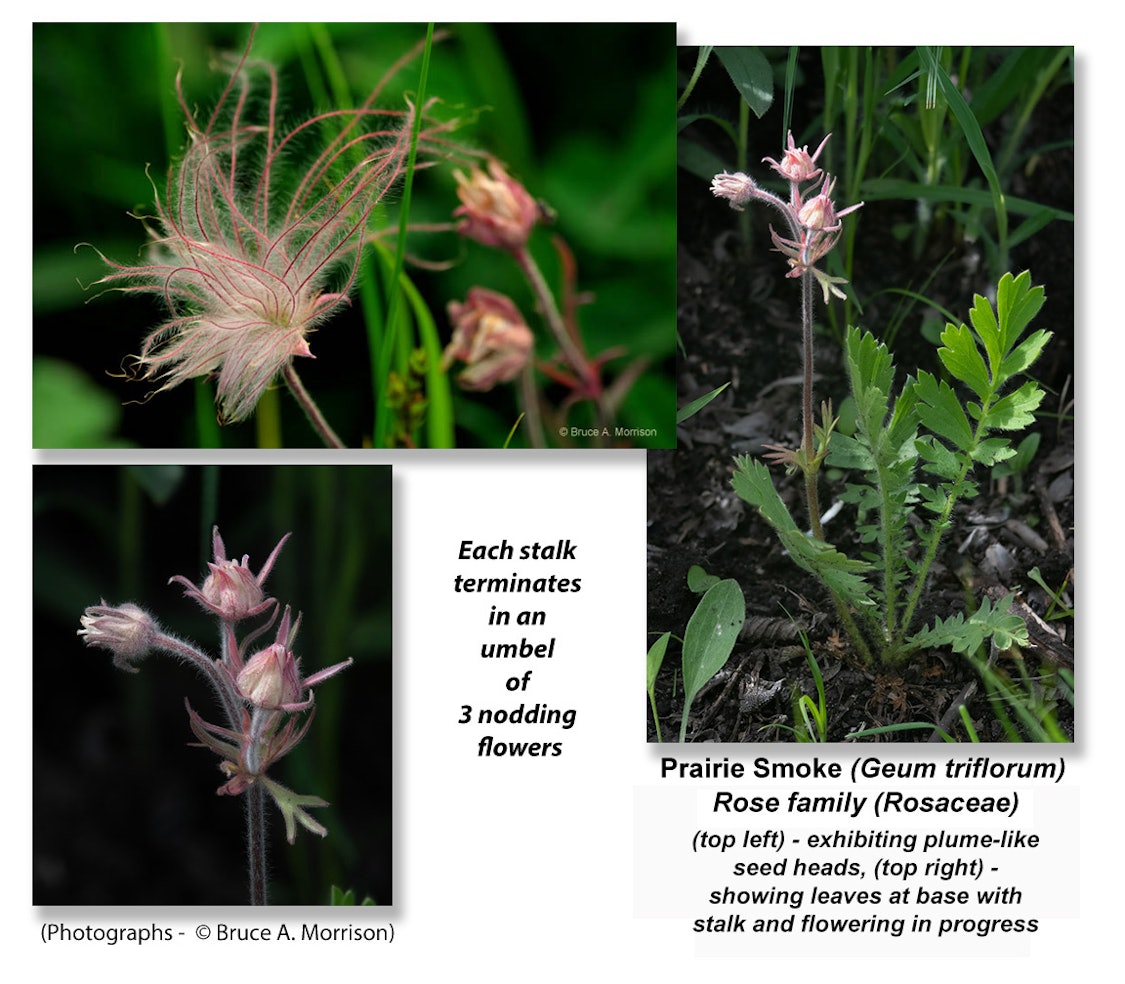

Then things started happening! It began as usual with with Starry Solomon seal, then Blue-eyed Grass, Prairie Spiderwort, Prairie Ragwort, and if we’re lucky, our first Prairie Smoke in several years will bloom!

Each year can be different, usually pleasant surprises abound. But some plants, like the prairie smoke, don’t always bloom. Some years, we’ll see the “plants” put up leaves but then that’s it.

Last year many things went dormant, and forbs and grasses that did bloom were much shorter in stature than usual. But we’ve had two or three other really dry summers in the 20 years we’ve lived here. Things usually show up again the following season.

Our two pastures are small. The north pasture abuts up against the neighbor’s pasture. His is so much larger and I’ve suffered pasture envy for years! The south pasture is small as well, and also butts up against the neighbor’s.

Our hillside driveway divides our acreage; the north side is approximately three acres, while the south side is just over one acre.

Small, yes, but we do have pasture buffers on each side of us plus a larger one across the gravel road out in front. We also benefit from the wildlife that spill over onto our property. The land in Iowa is so fragmented by agriculture; any corridors connecting habitat are a blessing for wildlife.

Much of the forbs and grasses on our ground were here already, yet due to very heavy grazing over the years, what we could find was often very sparse.

As I mentioned above, we had at least ten native species of grass. The first couple years we would cruise the “neighborhood” and watch for sources of seed to harvest to add to our pastures. There was Porcupine Grass and Prairie Cord Grass along the ditches just a hundred feet down the road from us, but these were missing here. Simple logic said it was likely here once as well. And the same thought persisted for other plants we’d find within the “neighborhood” and in the same soil types and slopes.

We’ve also collected seed from neighborhood forbs that we’d already found here on our own pastures – trying to increase existing populations. We’ve found nearly 50 types of forbs on the pastures through the years, and have added a handful of new plants that fit the location and soil type.

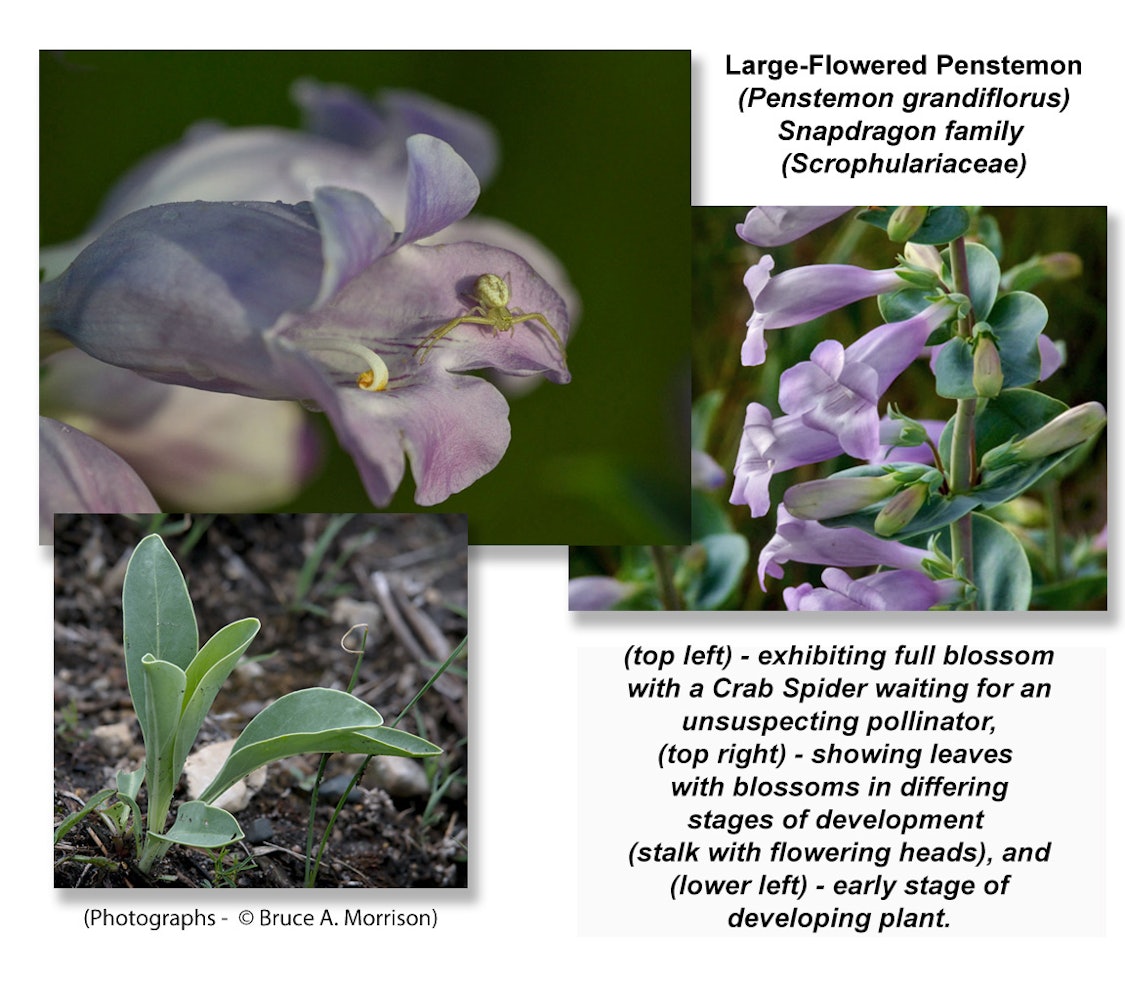

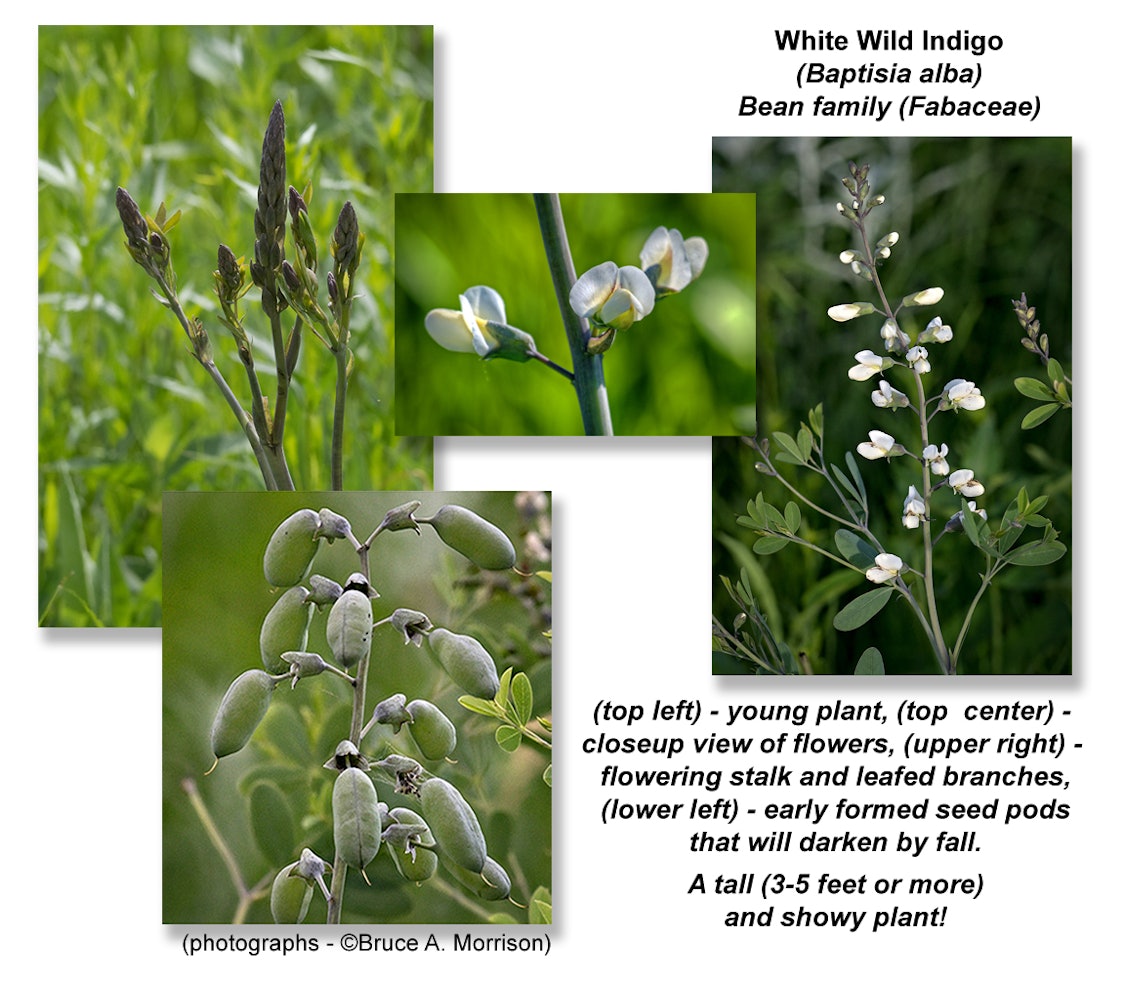

Some introduced forbs were Large-flowered Penstemon, Compass Plant, Anise Hyssop, Ground Plum, Prairie Lily, and White Wild Indigo. These were all found “near” us in natural areas with the same soil types – most were in gravely soils like our hill sides, others were found in mesic soil like our north and south pasture bottoms.

When working with or restoring prairie remnants, it’s helpful to show some restraint, limiting new plants to those that also exist in a reasonably close proximity, and in the same soil types and conditions.

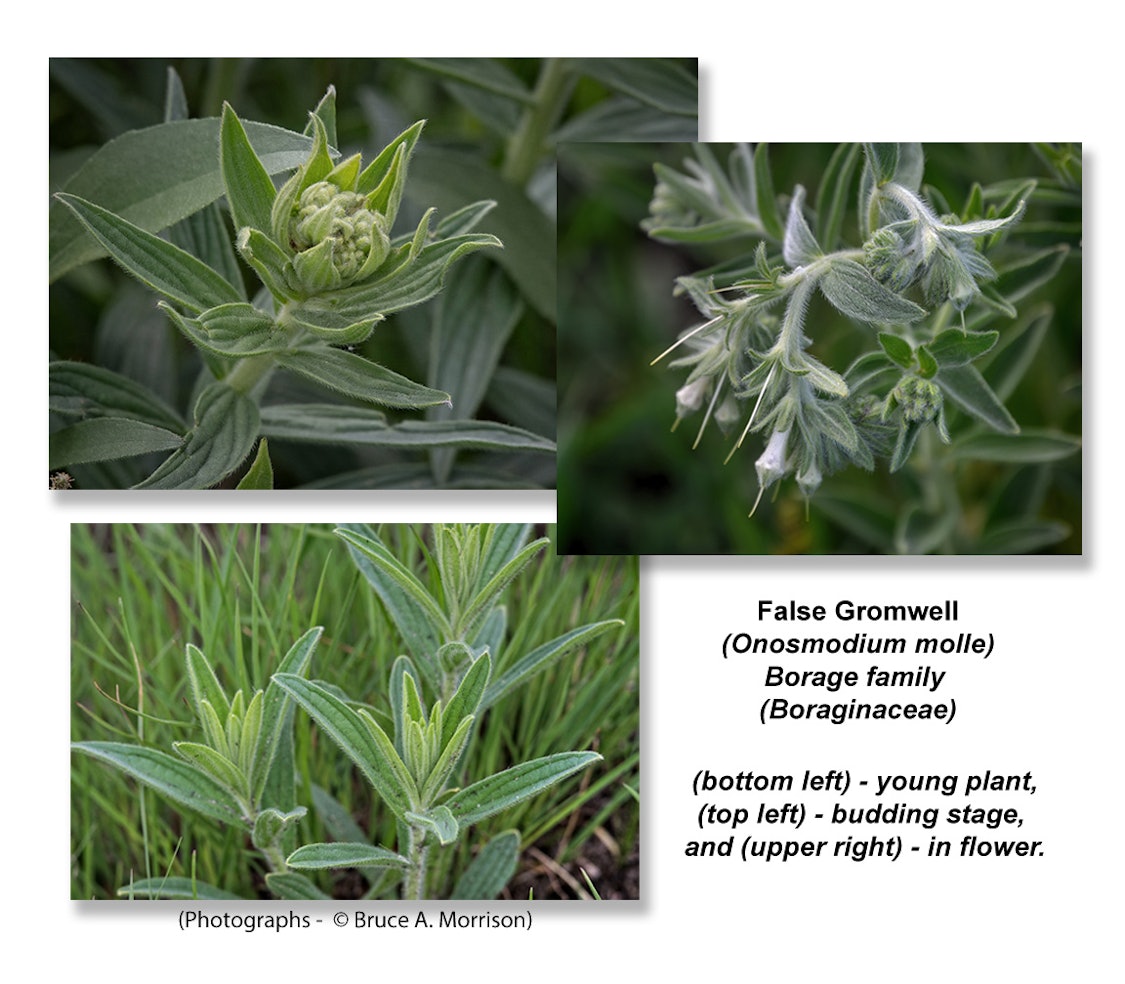

“False Gromwell with Prairie Phlox” (Onosmodium molle and Phlox pilosa) – color pencil drawing – ©Bruce A. Morrison)

“Canada Milk Vetch (Astragalus canadensis) – color pencil drawing – ©Bruce A. Morrison

This little piece of “what once was” is both a source of wonder and inspiration. I am a professional artist and photographer and will never run out of subject matter for paintings, drawings and photographs on this small remnant prairie and the surrounding countryside.

One of the things I’ve celebrated on canvas and drawing paper are the forbs and grasses of the prairie. I try to document them with the camera each year as well, of course, but there’s something more intimate about recreating bits and pieces of the prairie on paper or canvas.

“Big Bluestem in Bloom” (Andropogon gerardii) – color pencil drawing – ©Bruce A. Morrison

“Red Admiral on Swamp Milkweed” (Vanessa atalanta on Asclepias incarnata) – color pencil drawing – ©Bruce A. Morrison

It’s a renewed joy witnessing each day’s new plants and blossoms; the invertebrates they bring and depend upon; the wildlife that benefit from this habitat and food sources it provides. It all works hand in hand – everything is connected.

The brome pasture across the road has so many broken pieces, and the threads of its former self no longer can replicate what is across that graded gravel road separating us.

In the beginning I stated, “This little spot may not be on the super quality charts, but even places like ours are disappearing much too frequently.” I truly believe this.

This little piece of “what once was” is a gift for which we will always be grateful. We need to protect what we still have and pass it along. It is too important not to save for future generations!

7 Comments

This is fabulous!!!!!

I could rhapsodize about the photos and the species above, and mentally did that as I scrolled down. But I think it might be more helpful to offer a little advice to anyone who wants to do a prairie planting on a rural Iowa land parcel, large or small.

1) Find out the history of your land. If it’s a rowcropped field, has it been rowcropped for decades or just a few years? There are cases of some prairie plants coming back on cornfields that had only been cornfields for a few years, especially in parts of Iowa where tillage is not easy and soil is more sandy. It’s not common but not impossible.

2) If your land is pasture, or any permanent vegetation, don’t till or spray it until you have a good idea of what’s there. If possible, let the land grow for a full season and ID the plants. Overgrazed unmanaged prairie remnants don’t look like the lovely photos above. They can look really beat up but still hide surprising species and potential.

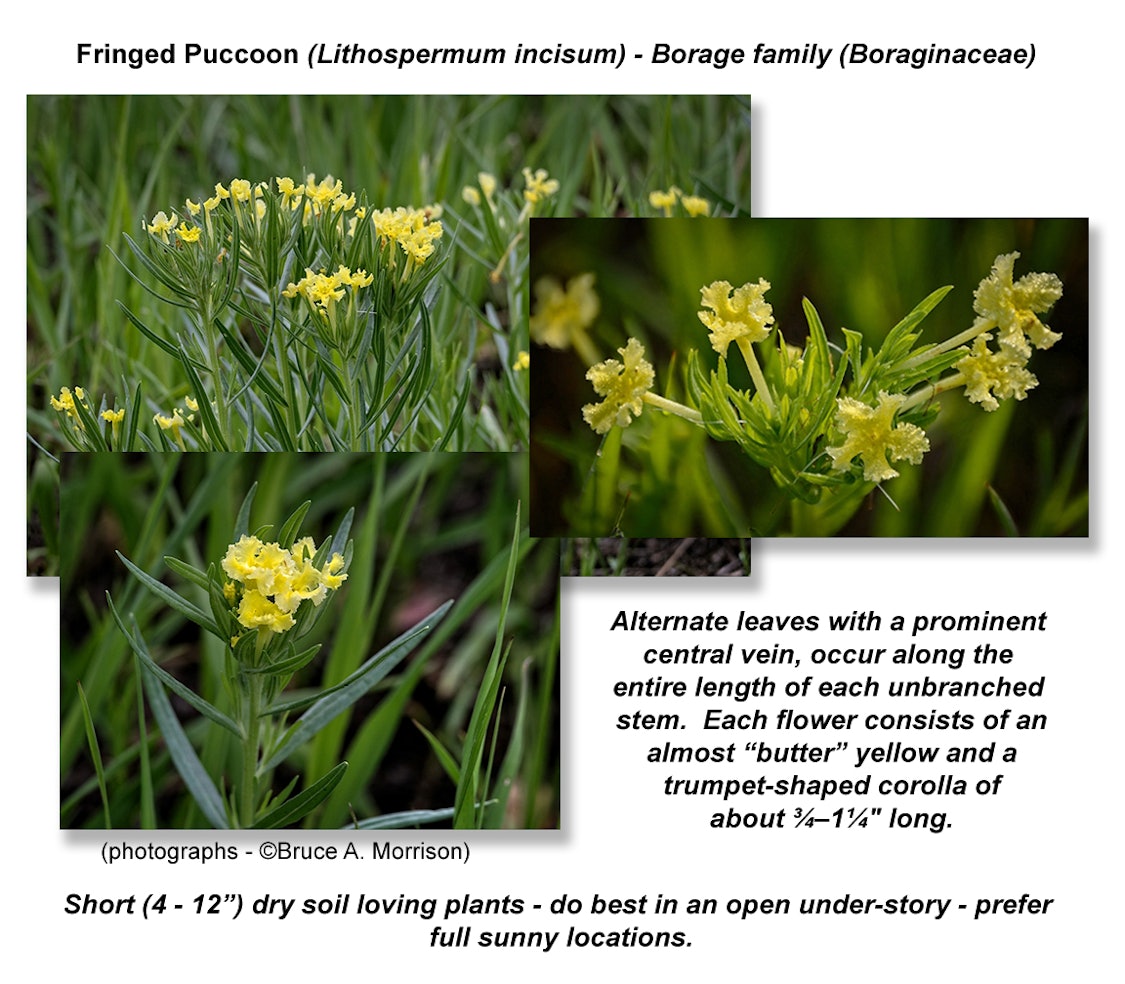

It can be painful to till or spray an odd grassy piece of land close to a creek, for example, and plant prairie seed, only to find out later that you very likely destroyed an existing remnant. (I’ve met a few regretful Iowans who did that.) Even great plantings can’t match the best remnants, and even degraded remnants can have beautiful prairie species that are hard to grow from seed and/or are rarely found in plantings, like the puccoon above.

3) In general, find out what your land has, preferably over at least a year, before plunging ahead with major changes. I’ve heard about prairie remnants that were turned into ponds, tree plantings, driveways, etc., and only later did the owners realize what happened. Knowing your land before making decisions can help prevent regret.

Thanks, Bruce! So beautiful.

PrairieFan Wed 15 Jun 8:54 PM

wonderful advice

Thanks for sharing your wisdom.

Laura Belin Wed 15 Jun 9:33 PM

Thank You!

Thank You Laura Belin, and thank you for your invitation to write a piece for Wildflower Wednesday!

Prairie Painter Thu 16 Jun 2:46 PM

Thank You!

Thank you PrairieFan!

Prairie Painter Thu 16 Jun 2:43 PM

On earth they're briefly gorgeous

Fabulous indeed. In addition, one should keep an eye on edges of timbers and even the edges of road ditches that blend into a field. And not only one year, even after one knows that some remnant forbs are present on a patch, the next year they may not be seen but then are in full glory a following year.

barry Thu 16 Jun 8:34 AM

Be Patient for sure!

Yes Barry, simply being patient and not jumping in blindfolded are important…not knowing what’s there “already” has hurt too many efforts by unsuspecting folks.

Prairie Painter Thu 16 Jun 2:49 PM

Good point!

Longer is better, and careful use of prescribed fire in ways that don’t burn everything all at once can help also.

PrairieFan Thu 16 Jun 4:36 PM