Terror gripped many Iowa Democratic hearts when the nonpartisan Legislative Services Agency (LSA) announced it would release a second redistricting plan on October 21. Governor Kim Reynolds soon scheduled a legislative session to consider the plan for October 28, the earliest date state law allows.

Democrats had hoped the LSA would spend more time working on its next plan. Iowa Code gives the agency up to 35 days to present a second set of maps. If lawmakers received that proposal in mid-November, Republicans would not be able to consider a third set of maps before the Iowa Supreme Court’s December 1 deadline for finishing redistricting work.

By submitting Plan 2 only sixteen days after Iowa Senate Republicans rejected the first redistricting plan, the LSA ensured that GOP lawmakers could vote down the second proposal and receive a third plan well before December 1. So the third map gerrymander—a scenario Bleeding Heartland has warned about for years—is a live wire.

Nevertheless, I expect Republicans to approve the redistricting plan released last week. The maps give the GOP a shot at winning all four U.S. House districts and an excellent chance to maintain their legislative majorities.

Equally important, state law and a unanimous Iowa Supreme Court precedent constrain how aggressive Republicans could be in any partisan amendment to a third LSA proposal.

IOWA SUPREME COURT MUST SIGN OFF ON THIS YEAR’S REDISTRICTING

The judiciary has not been directly involved in Iowa redistricting since the 1970s. But this year’s unprecedented delay in release of U.S. Census data changed the equation. Iowa’s constitution stipulates that if a redistricting plan “fails to become law prior to September 15 of such year, the Supreme Court shall cause the state to be apportioned into senatorial and representative districts to comply with the requirements of the Constitution prior to December 31 of such year.”

The Iowa Supreme Court has given the legislature and governor until December 1 to “prepare an apportionment,” following the procedures outlined in the redistricting law enacted in 1980, known as Iowa Code Chapter 42. But as that court order made clear, “the constitution now vests the supreme court with the responsibility and authority to ’cause the state to be apportioned.’”

In other words, the Iowa Supreme Court will need to sign off on legislative maps. That will be a formality if state lawmakers adopt one of the nonpartisan plans. But any partisan amendment to a third LSA proposal would surely prompt a lawsuit, forcing the court to consider whether the Republican gerrymander deviated from provisions in the state constitution or Chapter 42.

COURT ACTION ON A GERRYMANDER WOULD DRAW SCRUTINY

“Gold standard” is the number one cliché about Iowa’s redistricting process. The Supreme Court’s recent order used the phrase, indicating that the justices value the state’s reputation for fair maps.

Iowa lawmakers have never altered one of the LSA’s proposals. The legislature approved and the governor signed the third plan without amendment in 1981, the first plan in 1991, the second plan in 2001, and the first plan in 2011.

It would become a national news story if Republicans used their majorities to pass a partisan redistricting plan next month. Although Chapter 42.3 allows substantive amendments to the third LSA plan, Chapter 42.4(5) declares, “No district shall be drawn for the purpose of favoring a political party, incumbent legislator or member of Congress, or other person or group […].”

A lawsuit would force the Iowa Supreme Court to decide whether lawmakers amended the maps for an improper purpose.

Some Democrats believe the justices would rubber-stamp any action by a GOP-controlled legislature and the governor who appointed four of the seven current justices: Chief Justice Susan Christensen and Justices Christopher McDonald, Dana Oxley, and Matthew McDermott. (Terry Branstad appointed Justices Edward Mansfield and Thomas Waterman, and Tom Vilsack appointed Justice Brent Appel.)

The newest justice, McDermott, has done extensive legal work for the Republican Party of Iowa and represented Iowa House Republicans in an election contest less than three years ago. He did not recuse himself from election-related cases the court considered in 2020 and declined to comment on whether he would recuse himself from any post-election litigation, which ended up not happening here.

Asked whether McDermott would promise not to hear any cases related to redistricting, in light of his recent work for GOP lawmakers, judicial branch spokesperson Steve Davis told Bleeding Heartland on October 20, “The response remains the same” as last year.

I do not believe the court would allow an absurdly gerrymandered map to become law. Shredding our “gold standard” redistricting process would attract national attention and would severely undermine the court’s legitimacy.

Rather, I believe the justices would carefully consider whether any partisan amendment was consistent with Iowa’s constitution and the redistricting standards outlined in Chapter 42. The most important precedent in any such case would be In Re Legislative Districting of General Assembly, a unanimous decision from 1972.

A “FUNDAMENTAL ERROR” ON THE 1971 MAP

For many decades, Iowa had been grossly malapportioned, as most counties had one Iowa House representative, and the largest counties (which might have several times as many residents) had two House representatives. That changed following U.S. Supreme Court rulings from the 1960s, which required state legislative maps to be apportioned substantially according to population.

The LSA’s senior legal counsel Ed Cook has been involved in several rounds of Iowa redistricting. During a panel discussion the Harkin Institute organized in 2018, Cook explained that a 1968 amendment to the state constitution gave the Iowa Supreme Court original jurisdiction over redistricting disputes. The revised constitution also gave the court authority to draw the legislative plan if the one lawmakers passed was not valid. It’s not “you did it wrong, try again,” Cook emphasized. “They said, you failed to comply, we will then draw it.”

An Iowa Supreme Court ruling from 1970 rejected a map that had been drawn to protect certain incumbents, rather than with population equality “as nearly as practicable” in mind.

Following the 1970 census, Iowa’s GOP-controlled legislature approved a map that appeared to have little population deviation, Jean Lloyd-Jones recalled during that Harkin Institute panel discussion. In 1971, she was the newly-elected president of the League of Women Voters, an influential group at the time. She was surprised when the league’s lobbyists Betty Kitzman and Mary Garst told her the reapportionment plan had been gerrymandered, with changes made to accommodate legislative leaders.

A group of organizations including the Iowa Democratic Party, Iowa Federation of Labor, and Iowa Civil Liberties Union wanted to challenge the map in court. The League of Women Voters board was split on whether to join the suit. Some wanted to fight, while others worried they would “tarnish their nonpartisan reputation” by aligning with liberal organizations. Lloyd-Jones cast the deciding vote in favor of joining. The Iowa Supreme Court consolidated their appeal with two other lawsuits challenging the 1971 map on similar grounds. They appointed a special master to hear testimony and prepare a transcript and written summary for the justices to consider.

Richard Bender worked on redistricting issues as the Iowa Democratic Party’s executive director in the early 1970s. He explained during a recent telephone interview with Bleeding Heartland that Republicans “made a fundamental error” when drawing the lines. Polk County had about 10.1 percent of Iowa’s population, according to the 1970 census, but the legislature kept Polk County whole and gave it 10.0 percent of state legislative districts (ten of the 100 state representatives and five of the 50 state senators).

As the “data person” for the attorneys preparing the lawsuit, Bender used a t-test analysis, a statistical tool that looks at the chance of randomness and is still used in some challenges to gerrymandered maps. Democrats got it in the record that the t-test indicated the odds of the largest urban district getting shortchanged on the map by chance alone were more than a million to one. The League of Women Voters arranged for an Iowa State University statistics professor to explain what the t-test was and confirm that the formula used was correct.

Bender was present when other witnesses testified before the special master over a four-day period. His impression was that Iowa Attorney General Richard Turner, who led the Republicans’ defense of the map, “never really understood what was going on.”

Bender testified on a Friday, he told me, so the state had the whole weekend to prepare to refute his analysis. It was “amazing” to him when the Republicans called “a computer person” as a witness, whose only argument was that more statistical tests should have been used. “They didn’t get it! It’s not about computers, it’s about statistics.”

Lacking a grasp of the issues at play, Republicans never put together a solid defense of what could have been portrayed as not intentional but a “fairly minor screw-up” by the legislature, in Bender’s view.

Lloyd-Jones remembered another pivotal moment during the testimony. As Betty Kitzman testified about problems with the maps, a GOP attorney asked her, “Mrs. Kitzman, don’t you think you should have had some Republicans on your committee?” She smiled and said, “Sir, I am a Republican.”

Lloyd-Jones said the attorney “looked aghast” and said, “But you’re an impartial Republican.” She surmised that exchange “probably helped our case.”

A “CRITICALLY IMPORTANT” CASE FOR IOWA REDISTRICTING

The special master made no findings of fact or conclusions of law. But after reviewing the testimony, the nine Iowa Supreme Court justices agreed the 1971 map was unconstitutional.

They found that despite a Republican lawmaker’s denial, the legislature had used a “de minimis” approach, not permitted under the law, to draw the maps. Instead of making population equality a priority, lawmakers agreed on an acceptable amount of deviation between high and low districts. Then they drew the map to keep incumbents in office and avoid incumbent match-ups.

We feel the record before us is replete with testimony of witnesses tending to establish that districts were being created by House File 732 to facilitate keeping present members of the legislature in office and of providing boundaries of districts to avoid having such members contest each other at the polls.

Such considerations, which caused departures from the standards of population equality and compactness in the reapportionment districts, require us to hold House File No. 732 unconstitutional under both the Federal and State Constitutions. The same factors caused even greater avoidable deviations in the prior apportionment plan struck down by this court in Rasmussen v. Ray [the 1970 case mentioned above].

The justices further held that the League of Women Voters, which drew up its own redistricting proposal, had shown “plans more equal in population can be developed,” using the 1970 census numbers and following statutory requirements for contiguity and compactness.

Finally, the court determined,

Numerous districts in House File 732 are lacking in compactness. Nothing appears to indicate the strange shapes are necessitated by considerations of population equality or result from unfeasibility. The legislature failed to comply with the constitutional mandate to devise districts consisting of compact territory. As we interpret the Iowa Constitution, respondent had the burden of proof and he failed to sustain the burden to show why the legislature could not comply with the compactness requirement.

The LSA’s Cook said of the 1972 case, “The lawsuit is critically important to understanding how Iowa’s system came about. […] You see remnants of that court decision in Iowa statute.”

Darrell Hanson, a Republican who served in the Iowa House when the current redistricting law was adopted, told me in a recent telephone interview that the unanimous 1972 ruling was “traumatic” for many of his fellow GOP lawmakers. They did not want to have the court draw another redistricting plan. Some blamed the court-approved map for the party losing its legislative majorities in 1974. (Most political observers attribute that wave election to Watergate.)

Hanson sees the case as an important reason the GOP-controlled legislature agreed to codify the country’s first nonpartisan redistricting process in 1980. The 1972 precedent was also the main reason Republican lawmakers did not seriously consider amending the third nonpartisan plan submitted in 1981.

COURT RULING REMAINS RELEVANT

Hanson recalled staff advising House Republicans in 1981 that the Iowa Supreme Court would strike down a redistricting plan with larger population variances than the maps submitted by the Legislative Services Bureau (as the LSA was then known). The thinking was that any maps with larger variations in population—even if its districts were more compact—would fail for being “not as nearly equal as practicable.”

Bender communicated regularly with Iowa House and Senate Democrats in 1981. His perception, based on those conversations, was consistent with Hanson’s account. Republicans voted for the third map because they assumed they would lose in court again and were still “shell-shocked” by the 9-0 loss in the 1972 case.

By 1991, Hanson was part of Iowa House Republican leadership and was the top person working on redistricting matters in the caucus. Staff advice had not changed: if lawmakers approved maps that were less equal than the nonpartisan proposals, they would not survive judicial review.

LSA staff still interpret the relevant case law that way. The agency’s October 21 report to the Iowa legislature, containing new Congressional and legislative maps, responded point by point to the resolution Iowa Senate Republicans approved after rejecting the first redistricting plan. The Senate GOP had requested “a plan that better balances compactness with the legally mandated population deviation.” The LSA replied (pages 6 and 7, emphasis added),

The Legislative Services Agency agrees that both population equality and compactness are to be considered in developing a proposed redistricting plan for congressional and legislative districts. However, the resolution infers that both standards should be granted equal weight or that compactness should be granted more importance, relative to population equality, so long as “the legally mandated population deviation” is satisfied. The Legislative Services Agency contends that this inference, if it accurately reflects the intent of the resolution, is not consistent with Iowa Code section 42.4, the United States Constitution, or the Iowa Constitution. […]

Iowa Code section 42.4(1) provides, in general, that the legally mandated population deviation for both congressional and legislative districts are districts with a population as nearly equal as practicable to the ideal district population for such districts. While the Iowa Code section also provides a specified allowable deviation for congressional districts, numerous United States Supreme Court decisions have specifically rejected establishing an acceptable percentage deviation for congressional redistricting. Instead, the United States Supreme Court has consistently applied the “as nearly equal as practicable” standard, allowing only minor population deviations from congressional districts of nearly equal population for consistently applied traditional redistricting principles, such as, for example, Iowa’s whole county constitutional provision. Similarly, the Iowa Code section provides several allowable population deviation percentages for legislative districts. However, the Legislative Services Agency, since 1981, has consistently applied the strictest statutory deviation percentage, establishing legislative districts that do not vary from the ideal population of that district in excess of 1 percent. Reliance on this strict requirement is consistent with the decision of the Iowa Supreme Court in 1972 which rejected establishing an acceptable deviation percentage for legislative districts but instead required legislative districts to be as nearly equal in population as practicable. […]

The second congressional redistricting plan selected must be the one that best meets all the requirements of Iowa law, including the standard of compactness, while providing for equal or better population equality amongst districts. Since 1981, the Legislative Services Agency has followed this standard when submitting a second, and a third, plan of congressional redistricting. For 2021, the Legislative Services Agency followed this constitutionally directed mandate by submitting a second plan of congressional districting to the General Assembly of equal or better population equality amongst districts than the first plan submitted.

In other words, if House or Senate Republicans vote down the second redistricting plan on October 28, the LSA will come back with a plan that has an even smaller population variance between largest and smallest U.S. House district.

Assuming the Iowa Supreme Court views this matter in line with their predecessors, any Republican gerrymander would need to be more population equal than all three nonpartisan plans. That would be challenging to pull off while accomplishing other goals important to the GOP.

BEATING THE LSA IS “A PRETTY TOUGH GAME”

Speaking on behalf of Senate Republicans on October 5, State Senator Roby Smith laid out a series of pretexts for rejecting the first LSA plan. Some districts were supposedly not compact enough. As for population equality, he complained that eighteen of the 150 legislative districts were “within 100 people of exceeding or failing to meet” the legal standard of being no more than 1 percent above or below the ideal population.

During our interview, Hanson joked that this objection was “kind of like giving someone a speeding ticket because they were almost speeding.” If eighteen districts were within 100 people of failing to meet the standard, “that’s really another way of saying that all the districts met the state law.” Iowa Code sets out two ways to calculate population equality (mean deviation or range between largest and smallest district). Smith’s metric reflects neither of those standards. You could have fewer districts that are within 100 people of the limit and “still do a worse job of meeting one of the standards in the code.”

Hanson cautioned that he is not an attorney and hasn’t been involved in redistricting since 1991. But he noted that “by the floor manager’s own admission,” the LSA maps complied with all provisions in state law. So the legislature is free to adopt a different plan, but that plan would have to be at least as equal in terms of population. Otherwise it wouldn’t be “nearly as equal as practicable.”

Hanson told me years ago, “by the time the legislature gets to amend the 3rd plan, the universe of available options should be extremely narrow. […] I doubt there will be any room for the legislature to adopt a plan of its own that would pass legal muster AND provide a partisan advantage to the majority party.”

When we spoke early this month, his view hadn’t changed. “It’s a lot harder to beat the LSA’s maps than people might off the top of their head think it is.”

Bender agreed. If Republican lawmakers reject three nonpartisan plans, Democrats would have a prima facie case to say this is a partisan map. The burden would be on Republicans to show their map is superior to the maps they voted down.

Granted, the current Iowa Supreme Court “is a lot more partisan than the courts were in 1971,” in Bender’s opinion. Nevertheless, there is always uncertainty in going to court. Moreover, improving on the nonpartisan map “is going to be damn tough. I mean, the idea that you’re going to draw a partisan map and beat the Legislative Service Bureau map, that’s a pretty tough game.”

TEMPTATIONS TO GERRYMANDER

The most extreme examples of gerrymandering found on other states’ maps are not possible in Iowa, thanks to our statutory provisions on compactness and keeping counties and cities whole when possible. But a nonpartisan redistricting plan could still be tweaked to help one party in some way.

One example: While there is much for the GOP to like about the LSA’s Plan 2 for Congressional districts, that map would continue to “waste” a lot of GOP votes in the fourth district. Republican strategists reportedly preferred a Congressional map that would move Dallas County (Des Moines suburbs) to IA-04 and keep Pottawattamie County (Council Bluffs) in IA-03. What if they made that change on a third map amendment?

A plan that put Polk and Dallas counties in different U.S. House districts would guarantee that two members of Congress would represent residents of West Des Moines, Urbandale, and Clive. It would be difficult for Republicans to show any need to carve the state up that way, even if they could somehow beat the LSA maps on population equality while keeping districts reasonably compact. Under Iowa Code 42.4(2), the “number of counties and cities divided among more than one district shall be as small as possible.”

Gerrymandering the state legislative maps could lock in larger Republican majorities. Here are two of many possible examples.

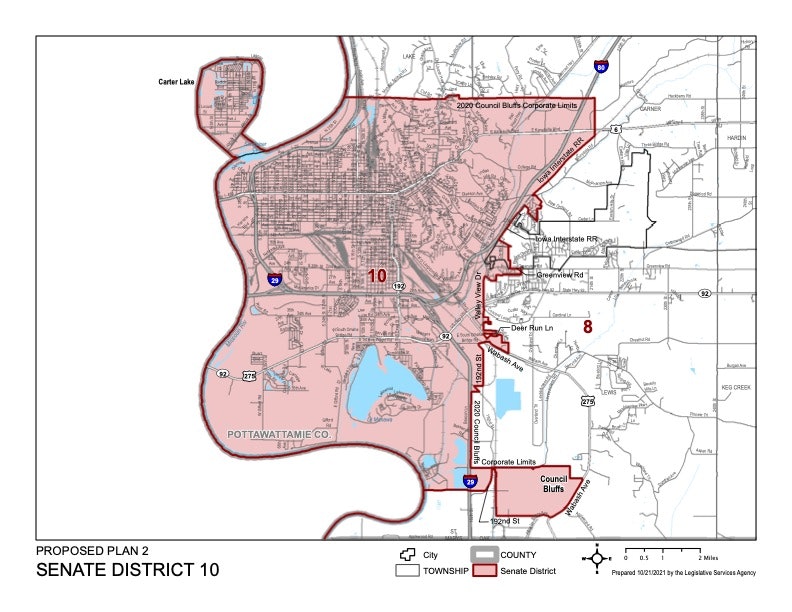

The city of Council Bluffs and Carter Lake (on the other side of the Missouri River) have been part of the same Iowa Senate district for decades. However, those cities’ combined population slightly exceeds the ideal for a state Senate district (63,807). The obvious solution is to leave out a small portion of Council Bluffs, as the LSA did in 2011 and again this year. The proposed Senate district 10, pictured here, nearly matches the current Senate district 8, represented by Republican Dan Dawson since 2017.

John Deeth has observed that Council Bluffs is a perfect candidate for a technique called “cracking.” The rest of Pottawattamie County and other nearby counties are deep-red. So Republicans could split Council Bluffs into two Senate districts and combine each half with mostly-rural areas.

That wouldn’t net them a Senate seat now, because they already hold all of the southwest Iowa Senate districts. But voters in the current Senate district 8 barely preferred Governor Kim Reynolds over Democrat Fred Hubbell (by 1 point) in the 2018 governor’s race. The result suggests that in a good year for Democrats, Dawson could be vulnerable in the new Senate district 10. Cracking his district would guarantee the incumbent’s safety even in an election like 2006, when Democrats took control of both legislative chambers and held the governor’s office.

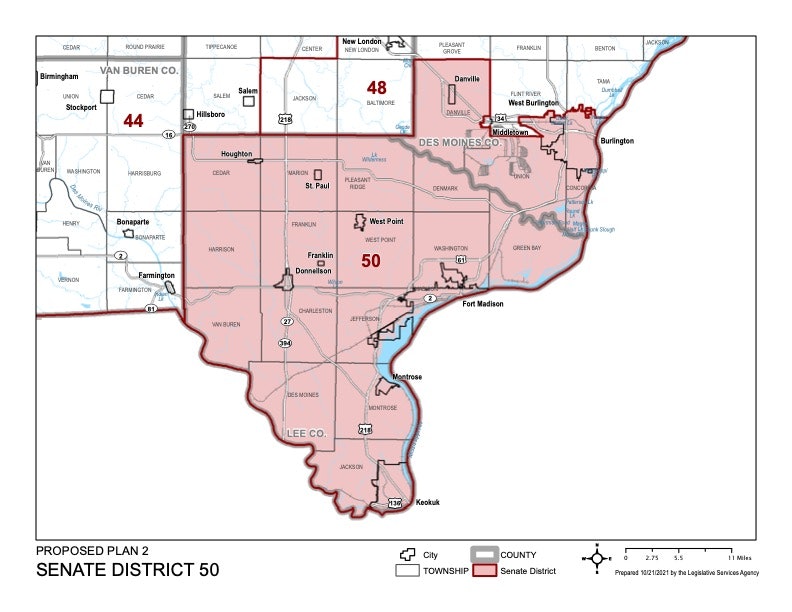

The LSA’s proposed Senate district 50 is another that Republicans might be tempted to change.

This district has two strikes against it. First, it contains two Republican incumbents: Tim Goodwin of Burlington (Des Moines County) and Jeff Reichman of Montrose (Lee County). It also would become a realistic target for Democrats in a good year for the party. Republicans would prefer to carve up this part of southeast Iowa to resemble the current map, on which the Senate districts containing Lee County and Des Moines County each pull in more Republican areas to the north.

Remember, state law expressly prohibits drawing a map to favor one party or certain incumbents. Republican witnesses denied that the 1971 map was drawn up to protect incumbents. But the Iowa Supreme Court concluded otherwise, based on the totality of the evidence.

Bender put it this way: if you’re the GOP staffer in the room where the decision is being made, how sure are you that the Iowa Supreme Court will break precedent for your alternative map? Given the national recognition of Iowa’s great redistricting system, the spirit gets stronger with every ten-year cycle. “It becomes more part of the culture of a place.”

Perhaps the current justices wouldn’t follow the 1972 precedent. Perhaps they would accept GOP claims that their partisan amendment was not designed to lock in a larger majority, or to protect sitting lawmakers. There is still an unavoidable risk that the court would deem the gerrymander unconstitutional. They might toss it out and enact the third LSA plan, which would have less population variance than the second (that is, be as “nearly equal in population as practicable”).

For all we know, that third nonpartisan map could be less favorable to Republicans than the one now before them. The safer route is to pass Plan 2 on October 28.

2 Comments

Redistricting

Terrific column. Perfectly sourced and cited. Thank you.

birminghan1@aol.com Mon 25 Oct 1:04 PM

Redistricting

First-rate analysis by one who knows. Thank you.

JamesSutton Wed 27 Oct 10:08 AM