An updated version of an essay published in 2020.

Connie Belin passed away on June 23, 1980. She was only 49. I was eleven, the youngest of her five children.

I’ve learned a lot from the defining event of my childhood, but it comes down to this: you never stop needing your parents.

Year 1

Although I saw my mother become sicker during 21 months of treatment for breast cancer, somehow her death still came as a shock. I remember realizing how bad things were when I was allowed to visit her in the hospital, a few days or perhaps a week before her death. Children under 14 were not normally permitted on that ward, and I had never been able to see her during previous hospitalizations.

The summer my mother died, my family muddled through. My father, my siblings and I stayed close to home. We went for long walks, we went swimming, we kept doing the things we used to do, except we also went to services every Friday night to say a special memorial prayer for my mother.

My friends said nothing to me about my bereavement. I remember asking another adult whether anyone had told them my mother had died. He explained that my friends did know what happened, they just didn’t know what to say. I felt relieved, because I didn’t want to talk about it. I dreaded having to tell people what had happened. I don’t think I was ashamed, but I quickly grasped that people became very uncomfortable when they learned you didn’t have a mother.

I have a vivid memory of my sixth-grade teacher asking the class, “Does your mother work?” (She seemed to be filling out some form.) She began calling on students in alphabetical order. Panicking, I tried to figure out how to answer this question. My teacher skipped over me.

My father hired a woman to baby-sit every day after school, even though I had a brother in high school who could have watched me. For that matter, at eleven I could have stayed by myself for an hour or two, but I was glad to have an adult around when I got home from school. She took me to piano lessons, chatted with me, did some housecleaning, and cooked supper for us all. I realized years later that my father was trying to protect me from having to take on my mother’s role in the house.

Before my mother died, I had become politically engaged as a supporter of John Anderson for president. My parents even brought me to the Republican presidential candidates’ debate before the Iowa caucuses. I mostly tuned out of the 1980 general election campaign, however.

My parents had a tradition of canceling out each other’s votes, dating to their first year of marriage (1952), when my dad liked Ike and my mom was “madly for Adlai.” I learned sometime during the 1990s that my father had secretly voted for Anderson instead of Ronald Reagan in November 1980. I don’t know whether he simply didn’t like Reagan or whether he couldn’t cast that vote without my mom around to cancel it out.

Year 2

Junior high school meant meeting a lot of new kids. I started developing a strategy for what to say when people who didn’t know my family history asked about my mother. Fortunately, the teachers all knew about my loss beforehand, so I didn’t face any awkward questions “in public.”

Several of my mother’s friends reached out to me during this time. One invited me to help make desserts at her house. Another became my regular shopping companion when it was time to buy back-to-school clothes, new shoes, or outfits for a special occasion. When you’re bereaved, small acts of kindness become magnified in your memory. I invited those women to my wedding almost two decades later, even though I hadn’t seen them in years.

My bat mitzvah in the spring of 1982 was the dominant event of the year. My father helped me a lot with the preparations, and we scheduled the celebration for spring break weekend, so my four older siblings could be there. You would think that it would be crushing not to have my mother around for this milestone, but my memories of the event are overwhelmingly happy. Looking through my old photo albums, my husband has commented that a stranger looking at my bat mitzvah pictures would never guess that my family had suffered a devastating loss so recently.

With my dad, David Belin, on the night of my bat mitzvah

Year 3

I’ve read that many people regain some emotional equilibrium about two years after a bereavement, and that held true for me. I had a strong group of friends at school and at summer camp. Although I had some down moments (Mother’s Day was a drag), I don’t remember feeling overwhelmed by being the only kid I knew whose mother had died. My father and I were very close. We talked about school and daily life, but also politics and current events. He didn’t talk down to me when we disagreed.

My father started dating, but fortunately from my selfish teenager perspective, he dated in another city where he frequently traveled for work. These women were not in my foreground, and I had a long time to get used to the idea of him seeing other women before I met one of his girlfriends.

Year 4

I had a smooth transition to high school. A lot of my teachers already knew my parents and older siblings. I stayed close to my core group of friends from junior high, adding some new friends through the debate team and my favorite class.

I don’t remember dwelling on my mother’s absence during this time, but other kids complaining about their moms became a pet peeve. All teenagers do that sometimes, but it stung, and I think it made me keep a little mental distance from people who had intact families. I doubt it was a coincidence that my first boyfriend in high school had an unusual home situation. He lived with guardians, even though his parents were alive. I never did get the whole story on that.

Year 5

Another wave of grief hit me during this year. I don’t remember any particular trigger, so maybe adolescent hormones or brain developments were responsible. Whatever the reason, I felt a lot more sorry for myself.

Other 15- and 16-year-olds were breaking as many rules as they could get away with, but I never went through a teenage rebellion. I couldn’t fight with or complain about my mother, because I had an idealized picture of her, and I didn’t want to push back against my father. I think I knew subconsciously that he had really come through for me in a crisis, and he didn’t need additional stress. Those feelings protected me in a way, because I never did the various stupid and dangerous things high school kids tend to do.

Year 6

At sixteen I started dating my “serious” high school boyfriend. We clicked on many levels—he was a smart, funny, cute guy. Looking back, I think I felt extra safe with him because his father had died a few years earlier. We didn’t talk much about our parents’ deaths, but we didn’t need to.

Year 7

By the end of high school, I felt I had fully accepted my mother’s death. Although I still missed my mother every day and wished I could have asked her a million questions, I believed I didn’t need to have my mother to have a good life. In fact, I remember thinking I’d rather have the one parent I had than the two parents most of my friends had.

As our group went through the college application process, one of my closest friends was accepted to her top choice. Her parents refused to pay for her to go to an out-of-state school. It wasn’t for lack of money—the following year, they bought an expensive new car. They reasoned that Iowa colleges were good enough for my friend’s older siblings, so they should be good enough for her. I was stunned that anyone’s parents would stand in the way of their child’s dream like that. My dad would have made major sacrifices, if necessary, to help me go to the college of my choice.

Year 8

Around this time I realized there was so much I didn’t know about my mother. For instance, I knew she loved college. She excelled academically, was with her best friends, and met her future husband. But I couldn’t remember hearing her talk about anything specific that happened in college, or what it was like the first year she lived away from her parents.

I talked to my father often, mostly about my classes and my new friends, but I didn’t feel comfortable asking him to tell me stories about my mother in college. Anyway, he didn’t even know her when she was a freshman.

Year 9

At age nineteen it occurred to me that as far as my conscious memories were concerned, I had lived as long without my mother as I had with her. That thought was depressing. I also became more aware of my fears that I might die at a relatively young age, before my own future kids were grown.

A great-aunt passed away that year. After her funeral, one of her daughters told me her mother had always identified with me, because she was the youngest child in a large family and had lost her mother at age nine. All the times we visited my great-aunt and uncle when I was growing up, she had never mentioned any of that to me. I wish we had had a chance to talk about it and about raising her own five children without her mother in the picture.

Year 10

I do not recall grieving deeply for my mother at this point in my life. I think I had reached another equilibrium. It helped that my dad and I were still close and spoke frequently. He helped me through the usual college crises, like not having started the paper that was due the next day.

Year 11

Another milestone approached as I entered my final year of college. My life was so different from my mother’s. At that age, she got engaged to my father and was training to become a teacher. I was planning a new adventure, going to graduate school abroad. I wondered whether she would have encouraged me to settle down, or whether she would have been excited about my opportunities. Probably she would have wanted me to go to grad school, as my dad did. She was a passionate feminist.

Year 12

I don’t remember any major steps in the grieving process during this year. My closest new friend in graduate school had a difficult family background; her mother could be described as “toxic.” When she would tell me about the latest outlandish thing her mom had done, I would think to myself, I am so glad I had the mother I had, even if it was only for eleven years.

In the spring of 1992, my father remarried. That occasion wasn’t easy for my siblings and me, but I liked my stepmother and thought she was a good match for my dad. I admit to feeling grateful my father didn’t remarry while I was in high school, living at home. The extra distance made it so much easier to accept my stepmother.

Year 13

The biggest challenge of this year was a bad break-up. Any loss tends to bring up unresolved feelings from past losses. The cloud lifted after a few awful months, in time for me to get to know my future husband.

Year 14

Having finished grad school, I came back to the U.S. for a job. It wasn’t a good fit, but living in New York allowed me to see my father and stepmother much more often.

My grandmother on my father’s side passed away after many years of poor health. Someone recalled after her funeral that she used to say she wished she could have died in place of my mother. I never heard her say that, but I was aware that she adored her daughter-in-law.

Year 15

I quit my job after nearly a year and started looking for work overseas, so I could live closer to my long-distance boyfriend. In the meantime, I came back to Iowa to volunteer for Bonnie Campbell’s campaign for governor in the fall of 1994. I stayed in my dad’s house, the house I grew up in, but it looked much different, because my stepmother had done extensive remodeling.

Living in the Des Moines area for the first time since high school, I came into contact with many people who had known my mother—old family friends as well as new acquaintances who recognized my surname. When strangers would tell me a story about my mother, I was touched that people still remembered her after so long. At the same time, those conversations reminded me how much I had missed by never knowing my mother as an adult.

Year 16

I was in a better frame of mind by the 15th anniversary of my mother’s death: living overseas again, adapting to a new culture, loving my new job (my first one as a writer), and getting to see my boyfriend every four to six weeks instead of every few months. My father and stepmother visited me during my first year in Prague, which was fun. Naturally, it would have been more fun to share my favorite views and places with my mother.

Year 17

My father had a health scare during this year. Oddly, I felt little fear about his condition. His underlying health was good, and I think psychologically I was not able to acknowledge any serious threat to his life. He recovered well, and I remember feeling glad he had my stepmother to help take care of him.

Year 18

This was a great year, and I don’t recall struggling with grief in any significant way. I was working long hours but loving my job and my surroundings. My boyfriend was spending a sabbatical year with me after years of dating long-distance.

Year 19

A promising beginning: my boyfriend and I decided to stop being a long-distance couple. When his sabbatical was up, I quit my job and went back to grad school in the UK. We were adjusting to life in London, and my father was planning to visit for my 30th birthday. One of my brothers got engaged. My sister got married, wearing our mother’s wedding dress.

Then a freak accident ended my father’s life in January 1999.

The year that followed was the worst of my life by far. My father’s death set in motion a painful chain of events for my siblings and me. My stepmother insisted on visiting me for my birthday (two months after the death), though she was the last person I wanted to spend time with. She meant well, wanting to give me the present my father had already picked out for me, but I felt like canceling my birthday.

I lost all interest in my academic work and freelance writing. I didn’t try to make friends in my new city. Finding a good therapist helped a little, but the bottom line was, I did not want to be a person without parents. Having one parent was a major part of my identity, and I was completely unprepared for losing my father. His doctor used to joke that he would live to be 100. His mother lived into her 90s.

For the first time in many years, I felt intensely jealous of people my age whose parents were alive. There they were, going about their business, having no clue what it’s like to have your family shattered. I mean, I was content to have one parent. Why did the universe have to take that away from me, and in such a flukey way?

I would go over and over the series of unlikely events that led to my father’s accident, thinking of all the ways some tiny thing could have led to a different outcome. If I couldn’t get my father back, I wished there were some magical way to swap him out for my mother.

While I was grieving for my father I often recalled a conversation I had had with a friend in college. His mother had died in a car accident during his senior year of high school. I said losing a loved one in an accident must be much harder. At least my mother had a chance to fight cancer, and I knew nothing could have saved her, given the technology available at that time.

His take was that when you think about it, dying from cancer or any other disease is just as random as a car accident. Why did his mother have to be in the wrong intersection at the wrong time? Well, why did my mother have to have a cell that started dividing and wouldn’t stop?

Year 20

When this year began, I was still at a low point following my father’s death. I had made no progress in my graduate research and didn’t see how I could follow through with a freelance writing commitment for the fall and winter of 1999/2000. Amazingly, though, the less bad days started to outnumber the very bad days, with some good days sprinkled in. As I battled through my freelance job covering the Russian parliamentary and presidential elections for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, my interest in the subject matter returned. My boyfriend was now my fiancé, and we started planning a wedding in my hometown the following year.

A great-uncle who had always been close to my father developed pancreatic cancer. I flew back to the U.S. for a cousin’s bar mitzvah so I could see him one last time. Other people cry at weddings, but since that weekend I’ve rarely made it through a bar or bat mitzvah without crying. Seeing the proud parents with their son or daughter is tough for me.

Year 21

I’m not usually one to get hung up on arbitrary dates, but the 20th anniversary of my mother’s death coincided with a close friend’s wedding weekend. I was one of her bridesmaids. She and her mother (a family friend whom I’d known my whole life) had offered to put on a Sunday brunch for the morning after my wedding. On June 23, 2000, my friend’s mother sprung on me that my stepmother wanted to do something for my wedding, so she was going to co-host the brunch.

It was too much. Since sixth grade I had known my mother wouldn’t be there for my wedding day. I was dreading my father’s absence for the celebration. Now my stepmother was barging in on my party. I called my fiancé in the middle of the night and cried for ages. Later that weekend I took my friend’s mother aside and told her that while I didn’t desire to exclude my stepmother from my wedding festivities, I would prefer for her not to host an event for me. Looking back now, I feel a little bad for hurting my stepmother’s feelings when she was trying to do something nice. At the time I felt a boundary had been crossed.

The wedding a few months later went well. Stealing an idea from my sister, we displayed photos near the guest book from my parents’ and my in-laws’ weddings. I felt comfortable including my stepmother in the wedding photos and procession, with one of my brothers walking her down the aisle. I got a little teary at one point during the ceremony, when the rabbi (an old family friend) reminisced about my parents. But it was truly a joyous occasion, not overshadowed by my parents’ absence.

Year 22

By the summer of 2001, I had found my equilibrium again. I no longer had trouble sleeping or searched for any excuse not to work on my dissertation. I missed talking things over with my father—news of the day, a chapter I was stuck on. But I was adjusting to the reality of having no parents.

Year 23

More big milestones: I finished my dissertation, and my husband took a sabbatical so we could move to Iowa, with a view to starting a family. Once we were back in town, I frequently ran into people who had known my parents. It had been years since I’d had daily contact with anyone who remembered them. As in 1994, the scattered memories I’d hear from family friends, business contacts, or casual acquaintances were moving.

Our first child was born that year, and I struggled during the postpartum period. My wonderful in-laws came to visit us twice, but I had so many questions I wanted to ask my parents. I had done little baby-sitting and hardly spent any time around babies before having one. I had never even changed a diaper.

Others could help me learn to take care of a baby, but I wanted to know what I was like as a baby, what it was like for my parents to take care of me, things they wouldn’t have changed and things they wished they’d done differently. It was devastating to think of my children never getting to know my parents, and my parents never having a single day to spend with my children.

Year 24

I wasn’t working outside the home and had plenty of time to read while I nursed or held my son in a rocking chair. I lost count of how many parenting books I read that year. I was drawn to attachment parenting.

As I learned more and watched my son develop, I understood how important that initial secure attachment to a caregiver is for babies and toddlers, not just emotionally but on a neurological level. When a child has a consistent, loving parent in the early months and years, that child develops the ability to trust and love. Even if trauma or tragedy disrupts the family bonds later, the child will forever benefit from that attachment.

As much as I still missed my mother on a daily basis, I again felt grateful to have received unconditional love.

Year 25

From what I remember, I was in a stable place during this year. My son kept me busy, and I enjoyed life with a baby and toddler even more than I thought I would. I don’t recall much grief during this year, but I did envy other moms whose parents were around to baby-sit or help them in other ways.

Year 26

My second child was born during this year, and the newborn period was intense. I felt much more confident about taking care of a baby, but parenting a baby and toddler simultaneously was challenging. I sought advice from other experienced moms, but of course I really wanted to talk to my own mother. How did she juggle things with two, three, four, and five children? I wished she could be there to play with my toddler so I could nap while the baby was sleeping.

I loved my in-laws and was happy to have them visit us, but on the days I watched my older son have the time of his life with Grandma and Granddad, I felt my parents’ absence deeply.

Year 27

By now my husband and I were getting the hang of parenting two children. But I still had so many questions about my childhood. Had my siblings or I done the same kinds of things my kids were doing at the various stages of development? How did my parents handle the annoying or frustrating behaviors that popped up from time to time? Honestly, I didn’t feel anything was missing from my life except my parents.

Year 28

The crisis of this year was a strep infection that got out of control and put me in the hospital for a week. Lying there, in pain with a fever, no appetite, and nothing to do, I desperately wanted my mother to come sit with me. When I had a couple of brief hospital stays as a child, my mother was with me the whole time. My sister flew to Des Moines to keep me company for a few days, which I appreciated so much, as my husband was tied up at home with our children.

During the spring of 2008, one of my brothers and I had a running argument about whether our mother would have supported Hillary Clinton or Barack Obama. I used to ask friends and relatives, who mostly agreed with me that she would have been for Hillary. I don’t know why we kept hashing out this unanswerable question. She didn’t live to see Reagan elected president, so how could we guess her views on Hillary Clinton?

Year 29

I turned 40 this year. Getting older didn’t bother me, but I often recalled that my mother never made it to 50. I occasionally wrestled with fears that I would not live to see my kids grow up. As a parent, I could better imagine the worries my mother must have had during her illness.

On the other hand, I realized that while I can’t control when or how I will die, my unconditional love should help my children cope when I’m gone.

Year 30

I thought the year leading up to the 30th anniversary of my mother’s death would trouble me more than it did. I must have reached another emotional equilibrium.

One painful moment stands out in my mind, though. My husband came across some family videos from a vacation we took when I was a teenager. As I pointed out my dad, my siblings, and me to my kids, my older son (age seven) asked, “Where’s your mom?” It hurt to tell him she had already died.

Year 31

A good friend battling multiple sclerosis had to move out of her home into a hospice in January 2011. We had bonded strongly after meeting through a parenting group four years earlier—a lucky chance, since she lived an hour away and rarely came to the Des Moines area. We had been getting our kids together every few weeks since 2007. She called our visits “extreme play dates,” because my son and I would often spend four or five hours at her house. She was happy for the company. Since she became unable to drive during pregnancy, she had been somewhat isolated.

I appreciated quality time with another adult while unfamiliar and therefore exciting toys kept my son occupied. We talked about politics, parenting challenges, pros and cons of living in Iowa, any book she was reading, our lives before kids.

We also talked frankly about her health. She knew there was a chance she might not see her son grow up, and I’ve thought quite a lot about that. I told her about learning to live without my mother, how my father and special family friends helped me through my bereavement. I reassured her that the unconditional love she’s given would serve her son well decades into the future, and that her husband’s strong bond with their son would also aid his healing.

Those early conversations happened when my friend had realistic hope that her MS would go into remission, or at least stop progressing.

When she declined to the point of needing hospice care, our boys were five years old, developing ever more elaborate games and routines. Watching her cheerful and energetic son, I was overwhelmed to think of all the milestones she would miss in his life, and devastated that this poor kid was about to have his world collapse on him. After a couple of months in hospice, my friend moved into the skilled care unit of her local hospital. It wasn’t a good space for children to hang out, but occasionally her husband brought her home for a few hours, so I could bring my son over to play.

Also during this year, my oldest brother had several hospitalizations related to chronic health problems. At one point, he was in intensive care, and things looked so bad I was worried I wouldn’t get out to see him in time. But it was a false alarm: he recovered reasonably well. When I called him, he invariably said he was “feeling good” and did not seem to want to discuss his health or other unpleasant subjects. We mostly talked politics and sports. I regret now that I rarely brought up our parents or childhood memories with him.

Year 32

I began visiting my friend more often alone. Her husband told me the play dates at home were too physically exhausting for her, so I stopped bringing my son down, except for special occasions like a birthday party.

Sometimes I attended her book club for women reading short stories by female authors. Other times I helped her edit a collection of personal writings that she hoped to self-publish. She was no longer able to type, nor could her eyes make out words on a computer screen, so I read passages out loud. Coming to terms with her deteriorating body was a running theme in her memoir.

I told my friend repeatedly that her son would be able to cope and even thrive, just like I had done despite losing my mother at a young age. I wanted her to believe that her son would be OK without her. Maybe I didn’t say enough about how much he would miss her.

Year 33

My friend and I worked on her manuscript with a growing sense of urgency as her health continued to decline. I started bringing my son for occasional play dates in the hospital. He and my friend’s son made paper airplanes and flew them in the atrium area. They played with toys and games and play dough in a family lounge area. Wanting to give my friend every chance to enjoy time with her son, the hospital staff were very tolerant, even when our boys (who were six and seven years old) got a little too excited and loud.

My friend spoke often of how she missed being able to do everyday things with her son. Of all the things multiple sclerosis had taken from her, that was the worst. I put on a brave face in her presence and usually cried in the car on the way home.

Year 34

This year turned out to be the hardest since 1999. My friend’s husband moved her from Iowa to a nursing home in another state, close to her family. He then moved with their son to a different state. I was enraged that a woman who had already lost too much would now see her son only every few months, rather than almost every day. She had no recourse, since her husband had medical and legal power of attorney.

Thankfully, we had finished editing the manuscript by the time she moved. Another friend and I worked with a local self-publishing firm on the final steps, like securing photograph permissions and blurbs for the back cover. We got proofs of her memoir into her hands less than a week before she died in January 2014.

The following month, my older son turned eleven. Having read Motherless Daughters by Hope Edelman, I was prepared for some additional grief and anxiety when my child reached the age at which I lost my mother. I never shared any of that with him, not wanting to make him feel self-conscious or worried something would happen to me. But sometimes when I looked at him, I couldn’t believe everything that had happened in my family, and how I hadn’t seen any of it coming.

My oldest brother passed away in March, triggering strong emotions for my siblings and me. He had survived many brief hospitalizations by that time, so none of us realized the end was near. Many cousins and quite a few friends who grew up in our neighborhood came out for my brother’s memorial service. I felt guilty for thinking it was just as well my mother wasn’t alive that day. She would have been so upset.

Year 35

Around the anniversary of my mother’s death, my older son passed the age at which I lost her. I loved the conversations he and I could have and wished I’d been able to share that stage of my life with my mother.

My father-in-law died unexpectedly on election night 2014. He had been suffering from a progressive disease, but we all thought he had years to live. My kids accepted the death easily—almost too easily. Although I was glad not to see them in distress, their reaction reminded me how little time they’ve had around grandparents, compared to many of their peers.

When Hillary Clinton kicked off her second presidential campaign, I thought a lot about how excited my mother would have been to see a woman become president.

Year 36

I didn’t spend ten seconds considering caucusing for Hillary in 2008, but I ended up standing in her corner on February 1, 2016, even though part of me felt that as a progressive I “should” caucus for Bernie Sanders.

Toward the end of this year, my older son had his bar mitzvah. Planning for the event was an emotional minefield. I’m not normally a superstitious person, but I think I was worried about inviting some catastrophe if I got too excited about the occasion. Everything went fine, and I managed to hold it together during the service.

Year 37

I often thought of my mother as I talked with the old ladies phone banking or writing postcards for Hillary. Health permitting, she would have been one of those 80-somethings volunteering as much as possible.

November 8, 2016 was the second time I can remember feeling it was better my mother wasn’t around to see what just happened.

The first half of 2017 was a stressful time to be covering Iowa politics from a Democratic perspective. I wasn’t grieving, exactly, but I felt perpetually exhausted and overwhelmed trying to “document the atrocities” of the new Republican trifecta.

Year 38

My younger son passed the age at which I lost my mother. I didn’t dwell on that much, but occasionally when he was upset, it struck me that he was so not ready to live without a parent.

I often reflected on how lucky my husband and I were to have easygoing kids, because I would have no clue how to handle a difficult teenager and no parents to consult.

Year 39

I was going to turn 50 in March 2019, but two other milestones loomed much larger in my mind.

January 2019 would mark the 20th anniversary of my father’s death as well as the point at which I would outlive my mother. We’d scheduled my younger son’s bar mitzvah for May of that year; seeing both kids become Jewish adults was a life goal.

I started thinking seriously about making some changes I’d long considered. One was dropping my blogger handle (“desmoinesdem”) and publishing here under my own byline. It was a difficult decision for reasons that are hard to explain to people who have only worked in traditional journalism.

The other was spending more time at the capitol. I’d had a vague plan to do that someday, when my kids were older. Near the end of 2018, I learned that due to retirements and cutbacks at other news organizations, fewer experienced statehouse reporters would be on the scene for the upcoming legislative session.

I rolled out my new byline on New Year’s Day and soon after submitted my application for credentials to cover the Iowa House and Senate. I figured, it would be more convenient to have a place to work in the building, and I’d have access to the press conferences. It had never occurred to me that Republicans who controlled the legislature and governor’s office would refuse to acknowledge me as a journalist.

My credentialing problems were first reported publicly in late January, while I was reeling from the reminders of how very long my parents had been gone. The battle became an ongoing distraction as I scrambled to cover the legislative session and take care of logistics for my son’s bar mitzvah. Keeping various press advocates and attorneys informed about what was happening took up way too much bandwidth.

The worst part was, the attorney whose advice I would have valued most had been unavailable for 20 years.

By some miracle, I didn’t drop any major balls related to the bar mitzvah and was not an emotional wreck during the service and reception. We had scheduled the event for Mother’s Day weekend, and it was without doubt my best Mother’s Day ever.

Year 40

The COVID-19 pandemic arrived a few months before the 40th anniversary of my mother’s death. In one sense, I was less affected than probably 99 percent of humanity, since I had been working from home for many years.

Yet watching the public health disaster unfold, I couldn’t stop thinking about the hundreds of thousands of people (including thousands of Iowans) who lost a parent to the virus.

When I read about the parents who left small children behind, I thought about what a painful journey lay ahead for those kids. I knew many of them didn’t have the privileges I enjoyed. For so many other children, having a parent’s life cut short may irreparably damage their physical and emotional well-being. It may mean losing a home or not having enough food on the table.

Two of my friends lost elderly parents that year. When I heard public figures downplay the fatalities by emphasizing that most who died were over age 65 or had underlying health conditions, I wanted to scream.

It’s heartbreaking when a parent passes away at any age, whether they lived independently or in a nursing home. In many cases, COVID-19 protocols deprived relatives of the chance to comfort their loved ones during their final illness. The pandemic disrupted funeral and burial rituals that can provide solace for the bereaved.

As for the pre-existing conditions, people who are immunocompromised or overweight are no less loved. People with diabetes or chronic conditions of the heart, lungs, or kidneys will not be missed less at their children’s weddings or their grandchildren’s birthday parties.

Year 41

Covering Iowa’s response to the pandemic consumed almost all of my work energy. It was a frustrating time professionally, because the state’s public health agency posted unreliable data on COVID-19 cases, positivity rates, and deaths, and the governor’s office stopped responding to open records requests.

On a personal level, I felt disheartened by how little changed as hospitalizations and deaths skyrocketed in the fall of 2020. The Trump White House Coronavirus Task Force repeatedly warned state leaders that “incomplete mitigation” efforts were causing “many preventable deaths” in Iowa. Yet the governor failed to take basic steps that could have limited the spread of the virus.

I couldn’t believe how many extended families were getting together for Thanksgiving and Christmas, as more than 1,000 Americans and dozens of Iowans were dying every day from COVID. Didn’t these people understand how lucky they were to have older relatives? If our parents had been alive (they would have been in their early 90s by that time), my siblings and I would never have risked their health for a holiday meal.

My immediate family mostly hunkered down at home. We were fortunate to have a good internet connection, so my husband and I could work while our kids logged in to school remotely. The year ended on a high note with our older son’s high school graduation. I was grateful to be there.

Year 42

My life changed in several ways. Our son went to college in another state. I became a plaintiff for the first time, in an open records lawsuit against the governor’s office. I continued to battle for credentials in the Iowa House and became a full-time paid employee of Bleeding Heartland after the House chief clerk moved the goalposts again. It made no difference; my application was denied.

I had another weeklong hospitalization after severely breaking my ankle in January 2022. The injury and long, painful recovery interfered with my work and with my capacity to raise money. I was now feeling a lot of pressure on that front, because on top of expenses like web hosting fees and technical support, I needed to cover my full-time salary to stay in compliance with the Iowa House media access policy.

Through the highs and lows, I often wished I could talk things over with my father. I’m embarrassed to say I rarely thought about seeking that kind of help from my mother. Clearly she would have had wisdom to share. I just didn’t have any frame of reference for getting her advice on a grown-up problem. I don’t know whether we ever had a phone call.

Year 43

I adapted to having only one child at home, getting around the state capitol with a lousy ankle, and balancing my writing with other work obligations.

The state asked the Iowa Supreme Court to dismiss our open records case, but the justices unanimously held that we could proceed with all of our claims. The state soon agreed to settle the lawsuit and pay the ACLU of Iowa for our legal fees.

Several plaintiffs had sought records from the governor’s office in 2020 and 2021. But thanks to the magic of alphabetical order, the case is known as Belin v. Reynolds. I told my husband to put that in my obituary.

Year 44

The high points were fantastic: quality time with my younger son during his senior year of high school, and my first chance to cover the Iowa House from the press bench, after the Institute for Free Speech filed a federal lawsuit on my behalf.

Grief wasn’t in my foreground. But some days, it didn’t take much to trigger me.

In the run-up to the 2024 Iowa caucuses, our governor often bragged about how she and her preferred presidential candidate charted their own course during the pandemic, instead of following the advice of public health professionals. Really? Her pandering to those who resisted masks, testing, and vaccines resulted in thousands of preventable deaths.

Despite our low population density, Iowa had a higher per capita death rate than many other states. If we had copied the mitigation policies of Wisconsin or Minnesota, an estimated 2,000 to 3,000 more Iowans would be alive today.

How many Iowans have questions about family history that no one can answer now? How many are raising kids who will never know their grandparents? How many children were forced to learn too soon how to manage without their primary caregiver?

Another trigger was when Republican operatives would cite my “trust fund” to discredit my work. The Iowa GOP’s state party chair likes to mock me as a “trust fund blogger.”

Most of the time I laugh at cheap shots from trolls. I haven’t figured out how to shake this one off.

I mean, guilty as charged: I couldn’t have shifted gears from my first career to covering Iowa politics without some income and a house that was paid for. I’m aware that I was extremely fortunate to be able to do this work without a salary for many years. Still, it wasn’t my choice to come into my inheritance before the age of 30. I would rather have my parents around and do something else for a living.

I never publicly acknowledged the comments, knowing any reply would only call attention to the insults and boost their engagement. Additionally, I feared that if Republicans knew this attack bothered me, they would use it more often and call in reinforcements to amplify it. I’m worrying right now that it’s a mistake to put any of these thoughts out there.

Year 45

I have lived four times as long without my mother as with her. Although losing her greatly affected my life, my grief is quite manageable. Compared to 20 or 30 years ago, or even ten years ago, I worry less about dying. I don’t feel that I was preoccupied with mortality before—it’s just a relief to know that whatever happens now, my kids won’t have to grow up without me. I never took that for granted.

When we became empty nesters, I didn’t go through the emotional upheaval that many parents experience. Of course I missed the boys and was happy to have them home for vacation. But I loved catching up on their courses and their lives. It feels like a huge accomplishment to interact with them as adults.

I still think often about kids I’ve known who lost a parent. A few months after my younger son went to college, I reached out to my late friend’s husband through Facebook. Their son is thriving too and strongly resembles his mother. She would be so proud. I wish she could see him now.

For decades, I’ve focused on how young I was when my mother died, and how many experiences I missed. Now that I’m in my 50s, I can see more clearly how young she was when she got sick, and how much that cost her.

I wonder what my mother planned to do once her kids were older. Would she have pursued a graduate degree or started a small business, like some of her contemporaries did? Did she hope to take up a hobby, or spend more time volunteering? Was there a city or country she always dreamed of visiting? I wish I could have known that side of her.

Living in the Des Moines area, I’m able to attend the funerals of family friends several times a year. No matter how old they were when they died, it’s hard on their loved ones. You never stop needing your parents.

6 Comments

Remembering the old ones

Thanks for sharing this Laurie. I wish I could have met your parents. They raised a wonderful daughter who has touched the lives of thousands. My mom died — and it seems impossible to say this — more than 50 years ago. There is scarcely a day goes by that I don’t think of her. I wish I had cataloged my feelings over the years as you have done. This is a great reminder to all — honor and remember the old ones. They aren’t finally dead until no one remembers them.

John Morrissey Thu 26 Jun 9:47 AM

You are the best!

Iowa Republicans mocking you? Ha! They got nothing! They are just jealous. They wish they had a reporter half as good as you—you who so skillfully skewer their small-minded, self-serving, mean-spirited agenda while avoiding the ad hominem and always dispassionately hitting your target.

As for being part of the market, I am about to contribute to your independence. Lord knows the Republican Noise Machine is lavishly funded by its Kochs, Scaifes, Mellons and other billionaires. Republicans have no room to talk.

May your flag always wave.

IowaVoter Fri 27 Jun 10:24 AM

thanks for sharing this

I’ve worked with several hospice programs, and grief is often a central theme for my analysands, and it’s painfully clear that we still don’t talk enough about death (and life after a death)

so that too many folks are caught off guard by what happens (of course going through it directly is different then hearing about it) and left isolated by the lack of social outlets/community that comes with collective silence. I’m sure your mom would be very proud of you and all you do for the rest of us

to try a make this a better place.

dirkiniowacity Fri 27 Jun 1:06 PM

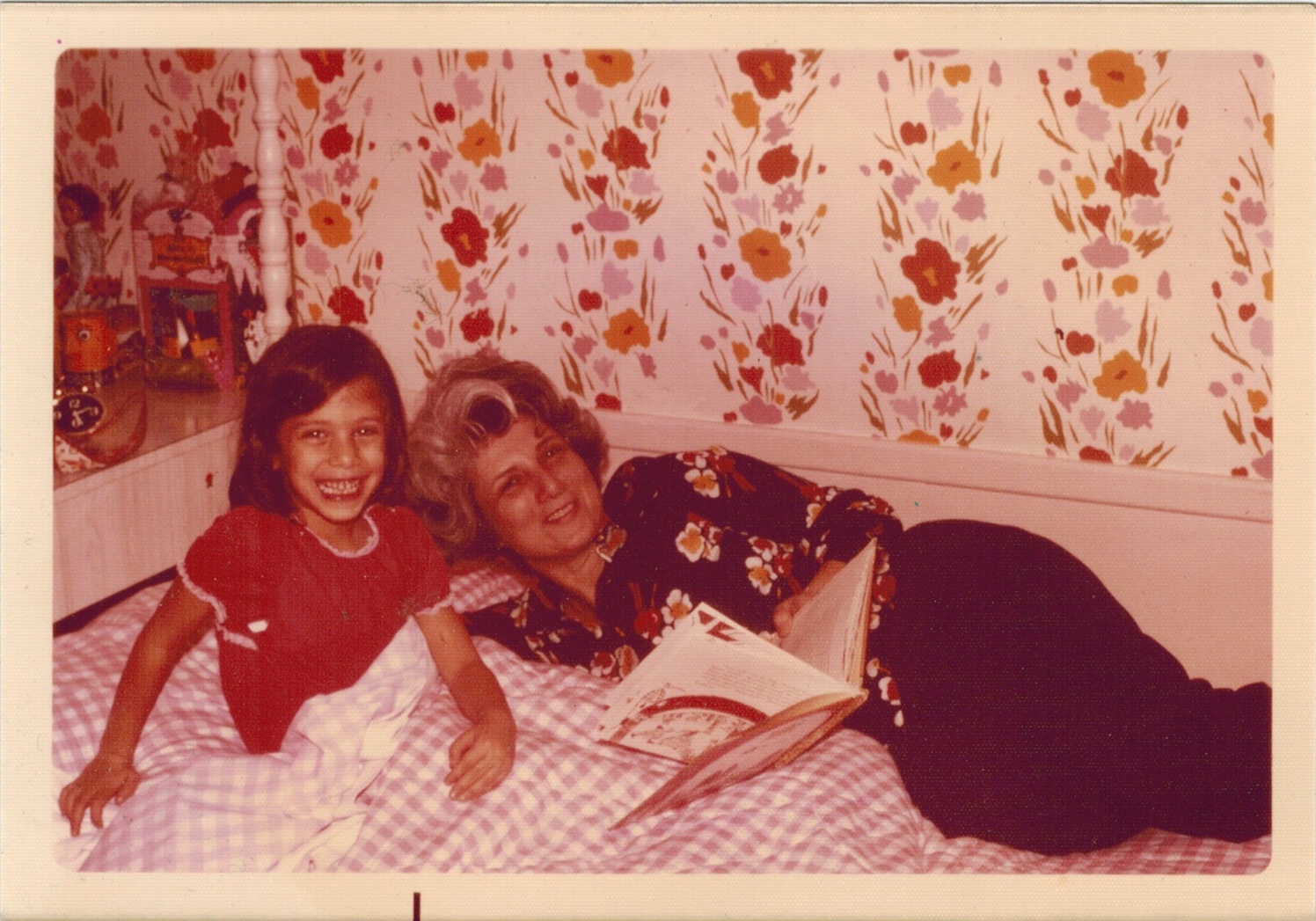

In that first photo, you look radiant with joy...

…and it’s heartbreaking to know how soon you would lose such a fundamental source of strength and joyfulness. Probably hundreds of people have told you over the years that your mother would be very, very proud of you. We say it because it’s so obviously true.

PrairieFan Fri 27 Jun 4:17 PM

Your Memoir Touches My Heart

Thank you for sharing this account of your life journey! It was a moving narrative of how you have confronted the pain that fate has dealt you, coping to the best of your ability in an evolutionary manner across the years, and being able to take your own life experiences and transform them into the tools by which to live a life of compassion and love that enhances the lives of others.

If I have learned one thing through my own 50 years in the rabbinate serving others and God, and especially through my own personal experiences of having, one by one, lost all the members of my childhood household, dealing with the challenges accompanying having a child (now an adult) with moderate to severe autism, and facing my own health crises, it is that our loved ones never really leave us and that in it all – the good & the bad – we can choose to either lose ourselves in our grief or, from our grief and challenges, grow deeper, wiser, and more appreciative of the blessings we did and do have. We can choose to seal ourselves within a bubble of pain or we can learn from our pain how to become better human beings while we work to ease the pain and suffering of others, seeking to make this world a kinder, more caring place, and in so doing, and in so doing, create for ourselves a living legacy of our own devotion to changing the world for the better. This is what you have been accomplishing, step by step, over the past 45 years.

Henry Jay Karp Wed 2 Jul 10:56 AM

are you serious?

The data shows now clearly that Covid vaccines did very little and the window of coverage was less than 3 weeks , then the effects of such tailed off dramatically. Every Iowa nursing home had mandates for vaccines , like it not and you still had plenty of older people with medical issues dying .

We then had many other old people who didn’t die and man6 never even got really ill. I have had positive tested covid 4-5 times down remember exact numbers, my doctor told me quit taking the vaccine , my health and being in my 50’s and the short term protection window was not worth it .

People who say you’re killing others without a vaccine? Pure fantasy as the window isn’t going to stop the spread , just as we have dealt with influenza for decades and decades and people still get infected even after the Vaccines , we can’t go into lockdown down for years , how ,any business closed ?

The billions lost with this scam of Covid ,and remember the mask? All made up poppy cock , even the great dr fauchy said the mask did little, he knew that as we saw him at the ball game with it off, and the governor of California having is high end private parties when they where outlawed , same with Nancy pelosi.

We have learned much and what do we hear today above Covid ? Deaths , vaccines and what they are showing in children?

I’m not allowing politics to play into my vaccine schedules , I’ll listen to my doctor.

Midwestconservative Fri 4 Jul 9:10 PM